Abstract

This research deals with implementing Dental Prenatal Care as a public policy in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) to care for pregnant women and their future babies. The legal framework that assures pregnant women's rights of priority in accessing services is usually not enough to guarantee the health promotion coverage goals for this population group, who frequently have low adherence to dental care. Brazilian Unified Healthcare System (SUS) recommends monitoring pregnant women through eight mensal consultations during healthy pregnancy. Oral health is usually not monitored to the same extent, and many pregnant women still go through pregnancy without any dental consultation. This study was proposed to improve dental prenatal care and program adherence by mothers and children in the Basic Healthcare Unit Amaro José de Souza, in the municipality of Barueri, through the increased participation of the dental surgeon in the pregnant women welcoming team. A cross-sectional cohort study was designed to identify and meet the demands of low-risk pregnant women. For six months, all the women attending prenatal care at BHU Amaro José de Souza in Barueri were invited to participate and receive personal guidance from the multi-professional team. Information on dental health was investigated through questions targeting previous knowledge about the recommended moments for the first dental appointment of a child, the importance of exclusive nasal respiration, the identification of craniofacial asymmetries at birth, and general baby care. Attitudes and self-care were also investigated, including prenatal program adherence. Answers were collected in a Google Form platform and analyzed to characterize the group's literacy about prenatal care and breastfeeding and identify information needs about dental health care during pregnancy. At the same time, a welcoming expanded listening, educational, and preventive health action was developed: conversation and sharing experience groups were promoted monthly for pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, and their families. 90 pregnant women out of the 104 attending the BHU in the six months of the research were invited, and 83 agreed to participate. All the participants declared at least one previous appointment with the healthcare team, 92.8 % of them, with a gynecologist. The nursing team was involved in 53.0 % of the appointments, but only 6.0 % were reported to have been conducted exclusively by a nurse. A dental surgeon appointment was mentioned by 30.1 % of the research participants. The dental health literacy investigation revealed that 57.8 % believed they should only take their babies to a dental appointment after teething, and 27.7 % were aware of the child's craniofacial asymmetries at birth. Only 28.9 % had previous knowledge about the importance of exclusive nasal respiration. Despite only 34.9 % having their first pregnancy, 78.3 % declared they would appreciate receiving information about pregnancy. After the guidance, 72.0 % of the pregnant women had undergone dental prenatal care. Workshops for pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers provided a convenient welcoming space, to listen and provide guidance to pregnant women and their families, in addition to demystifying the fear of dental care during pregnancy and breastfeeding. The intervention to guide pregnant women to perceive the BHU as an educational and health promotion space, not just a curative intervention, effectively increased adherence to dental prenatal care. The contact with the Specialist in Functional Jaw Orthopedics in this first phase of life facilitated dental health education and access to more complex cases. The prenatal program adherence, the pregnant woman’s self-care, and the care of the baby were favored by the welcoming, expanded listening, and personalized service.

Highlights

- The dental health literacy investigation revealed the relevance of information about dental prenatal care.

- Pregnant women perception of the BHU as an educational and health promotion space increased adherence to dental prenatal care.

- Dental health education facilitated access to complex cases.

1. Introduction

Dental prenatal care is a public policy in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) to care for pregnant women and their future babies. This research deals with implementing this policy and promoting the health of pregnant women who frequently have low adherence to dental care. The legal framework that assures pregnant women’s rights of priority in accessing services is usually not enough to guarantee the health coverage goals for this population group [1]. Brazilian Unified Healthcare System (SUS) recommends monitoring pregnant women through eight mensal consultations during healthy pregnancy. Personalized care and additional monitoring must be considered if there are any complications. Whatever the situation, a pregnant woman's journey accesses care predominantly by gynecology and nursing specialties in public healthcare services. Oral health is usually not monitored to the same extent, and many pregnant women still go through pregnancy without any dental consultation.

2. Objective

This study was proposed to improve dental prenatal care and program adherence by mothers and children in the Basic Healthcare Unit Amaro José de Souza, in the municipality of Barueri, through the increased participation of the dental surgeon in the pregnant women's welcoming team.

3. Methodology

A cross-sectional cohort study was designed to identify and meet the demands of low-risk pregnant women. For six months, all the women attending prenatal care at BHU Amaro José de Souza in Barueri were invited to participate and receive personal guidance from the multi-professional team. The program consisted of responding to a questionnaire presented to each woman on a mobile phone, to be fulfilled after agreement with the research terms and signature of a free and informed consent form. Information on dental health was investigated through questions targeting previous knowledge about the recommended moments for the first dental appointment of a child, the importance of exclusive nasal respiration, the identification of craniofacial asymmetries at birth, and general baby care. Attitudes and self-care were also investigated, including prenatal program adherence. Answers were collected in a Google Form platform and analyzed to characterize the group's literacy about prenatal care and breastfeeding and identify information needs about dental health care during pregnancy. At the same time, a welcoming expanded listening, educational, and preventive health action was developed: conversation and sharing experience groups were promoted monthly for pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, and their families. The administrative staff and the healthcare multi-professional team participated in training workshops before they were allowed to welcome pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers in such groups. These workshops focused on interprofessional practices, optimized humanization, and the newly recommended approaches for oral health promotion in pregnancy.

4. Results

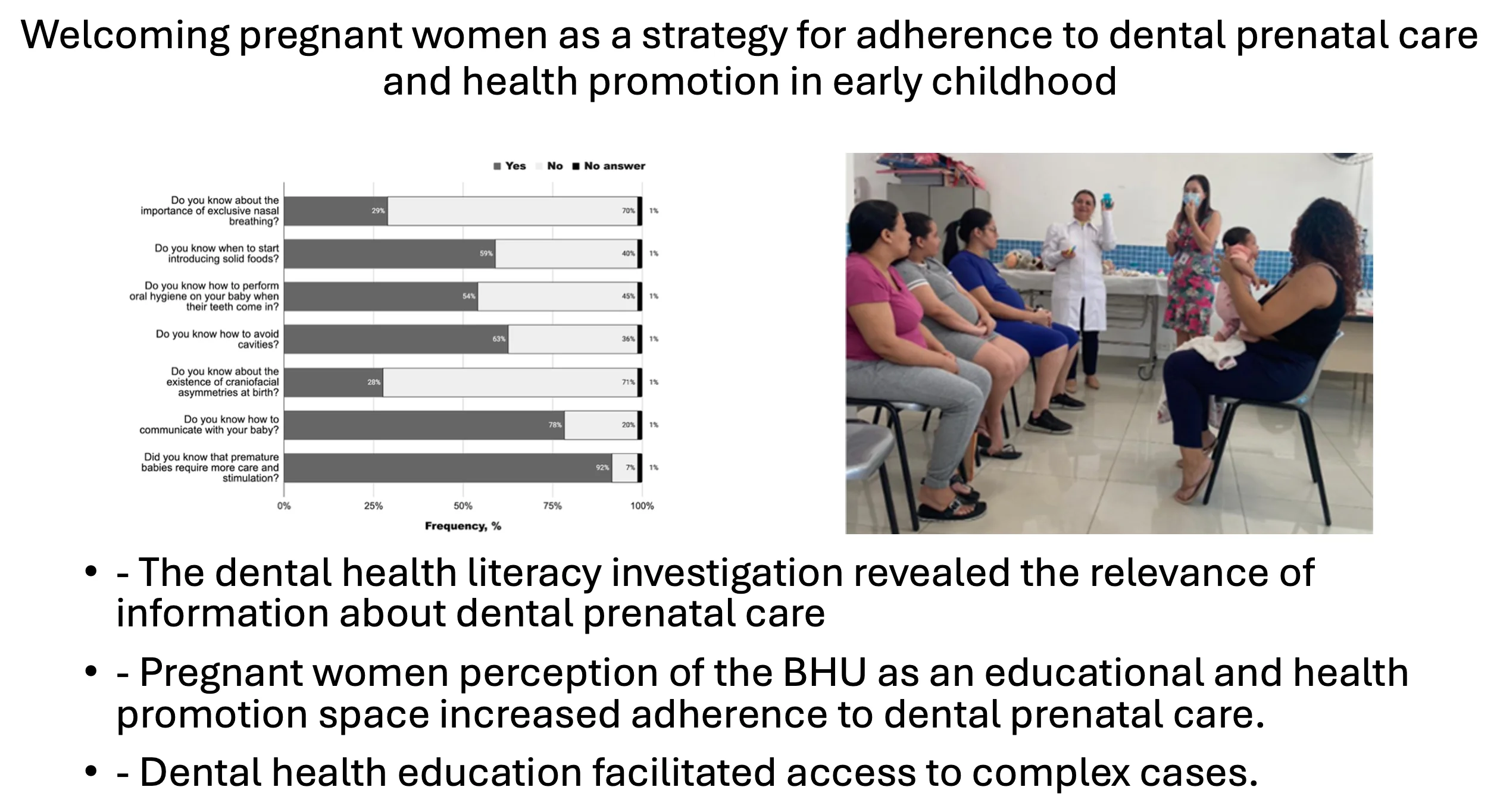

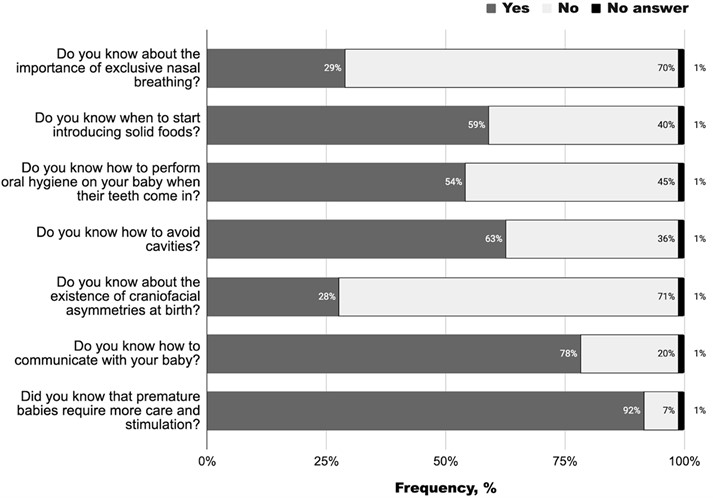

90 pregnant women out of the 104 attending the BHU in the six months of the research were invited, and 83 agreed to participate. The participants were in the 2nd to the 9th pregnancy month and declared at least one previous appointment with the healthcare team, 92.8 % with a gynecologist. The nursing team was involved in 53.0 % of the appointments, but only 6.0 % were reported to have been conducted exclusively by a nurse. A dental surgeon appointment was mentioned by 30.1 % of the research participants. Other professionals mentioned were general practitioners, community health agents, pharmacists, pediatricians, nutritionists, psychologists, and social assistants. Despite only 34.9 % having their first pregnancy, 78.3 % declared they would appreciate receiving information about pregnancy, and 95.2 % intended to breastfeed their babies. The dental health literacy investigation revealed that 57.8 % believed they should only take their babies to a dental appointment after teething, 15.7 % during the first year, 20.5 % when they complete the first year, and 4.8 % only if the baby suffers from pain. Other questions’ response distributions are shown in Fig. 1. After the guidance, 72.0 % of the pregnant women had undergone dental prenatal care. Workshops for pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers provided a convenient welcoming space, to listen and provide guidance to pregnant women and their families, in addition to demystifying the fear of dental care during pregnancy and breastfeeding (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1Dental health literacy results among women attending prenatal care at BHU Amaro José de Souza in Barueri who agreed to answer a questionnaire and receive personal guidance from the multi-professional team (n= 83). Health education and promotion interventions were provided to improve the dental health literacy of the responding group

Fig. 2Health education and promotion workshops for pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers were conducted in the Basic Healthcare Unit Amaro José de Souza, in the municipality of Barueri. Pregnant women were encouraged to adopt breastfeeding and undergo prenatal dental care

5. Discussion

Dental prenatal care policy implementation and active health promotion programs help to improve adherence to prenatal dental care of women who, in most cases, still require curative dental treatments. A multidisciplinary educational approach can increase awareness about the connection between oral health and pregnancy outcomes in the pregnant woman's journey in the SUS. Permanent education of the multi-disciplinary team is recommended to implement cooperative interprofessional practices that ensure the development of pregnancy, maintain maternal and child health, early detection and management of pre-existing conditions or comorbidities, and reduce maternal and child mortality [2], [3]. It was previously reported that the dental guidance received during pregnancy influences mothers in the procedures adopted with their children, concerning the beginning of oral hygiene [4]. The integration of the dental surgeon into the interprofessional team confirmed the potential of cooperative practices to promote the bond, favoring adherence to prenatal care dental care, promoting breastfeeding, and stimulating the acquisition of good eating habits and oral hygiene [5]. The patient journey follow-up by the dental surgeon is recommended for all age groups, this professional expertise can improve effective individual and family care from early life on.

The Functional Jaw Orthopedics Specialist Dental Surgeon can help the healthcare team protect pregnant women's health and promote harmonious child growth and development, improving quality of life and reducing the need for curative and invasive treatments. It is very relevant to prevent malocclusion from the beginning of prenatal care until early childhood through periodic assessment during the first two years [6]. Cranial deformities are common complaints in pediatric units, as 25 % of children with single pregnancies and 50 % of those with multiple pregnancies have some degree of skull deformity at birth [7].

First-time pregnant women can be encouraged to take oral health care and adopt breastfeeding after observing postpartum mothers who breastfeed, as preconized [8]. Follow-up programs, in Primary Care, facilitate patient-centered prenatal and postnatal care in cases of changes in breastfeeding, gingival rounds, asymmetries already present at birth, or changes in the sucking, swallowing, and subsequent functions of chewing, with positive repercussions from pregnancy to maturity.

6. Conclusions

The intervention to guide pregnant women to perceive the BHU as an educational and health promotion space, not just a curative intervention, effectively increased adherence to dental prenatal care. The contact with the Specialist in Functional Jaw Orthopedics in this first phase of life facilitated dental health education and access to more complex cases. The prenatal program adherence, the pregnant woman’s self-care, and the care of the baby were favored by the welcoming, expanded listening, and personalized service.

References

-

“Law no. 13,257,” Brasília, Official Gazette of the Union, Mar. 2016.

-

C. Bastiani, A. L. S. Cota, M. G. A. Provenzano, M. L. C. Fracasso, H. M. Honório, and D. Rios, “Knowledge of pregnant women about oral changes and dental treatment during pregnancy,” (in Portuguese), Scientific-Clinical Odontology, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 155–160, 2010.

-

M. L. A. Araújo et al., “Health education – comprehensive and multidisciplinary care strategy for pregnant women,” Revista da ABENO, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 8–13, 2011.

-

T. S. P. Lopes, C. C. B. Lima, R. N. C. Silva, L. F. A. D. Moura, M. D. M. Lima, and M. C. Pinheiro Lima, “Association between duration of breastfeeding and malocclusion in primary dentition in Brazil,” Journal of Dentistry for Children (Chicago), Vol. 86, No. 1, pp. 17–23, 2019.

-

L. Rigo, J. Dalazen, and R. R. Garbin, “Impact of dental orientation given to mothers during pregnancy on oral health of their children,” Einstein (São Paulo), Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 219–225, Jun. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082016ao3616

-

M. Martini, A. Klausing, G. Lüchters, N. Heim, and M. Messing-Jünger, “Head circumference – a useful single parameter for skull volume development in cranial growth analysis?,” Head and Face Medicine, Vol. 14, No. 3, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13005-017-0159-8

-

E. Ghizoni, R. Denadai, C. A. Raposo-Amaral, A. F. Joaquim, H. Tedeschi, and C. E. Raposo-Amaral, “Diagnosis of infant synostotic and nonsynostotic cranial deformities: a review for pediatricians,” Revista Paulista de Pediatria (English Edition), Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 495–502, Dec. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rppede.2016.02.005

-

“Topics: maternal health 2022.” Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization, https://www.paho.org/pt/node/63100.

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Renata Mendes Orsi: conceptualization, investigation, project administration, writing- original draft preparation. Lígia Ferreira Gomes: methodology, supervision, writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The research adhered to all applicable laws and ethics standards. Permission to perform clinical trials investigation was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences of the University of São Paulo, number 6126527/2023, on June 19, 2023. Participants provided written informed consent before the research.