Abstract

The bending analysis of symmetric cross-ply laminated plates in a hygrothermal environment is presented. The sinusoidal shear deformation plate theory is used for this purpose. It enables the trial and testing of different through-the-thickness transverse shear-deformation distributions and, among them, strain distributions that do not involve the undesirable implications of the transverse shear correction factors. The governing differential equations for the bending of laminated plates are obtained using various plate theories. Displacement functions that identically satisfy boundary conditions are used to reduce the governing equations to a set of coupled ordinary differential equations with variable coefficients. Numerical results for deflection and stresses are presented. The effect of different types of sinusoidal hygrothermal/thermal loadings is investigated. The influence various parameters such as material anisotropy, aspect ratio, side-to-thickness ratio, thermal expansion coefficients ratio and stacking sequence on the hygrothermally induced response is also investigated. A concluding remark is made.

1. Introduction

The degradation in performance of the structure due to high temperature and moisture concentration has become increasingly more important in many structural applications. The analysis of the rectangular plates subjected to hygrothermal effects has been the subject of research interest of many investigators. Moisture and temperature may be distributed through the volume of the structure and may induce residual stresses and extensional strains. These residual stresses and extensional strains may also affect the gross performance of the structure. In particular, the bending characteristics, buckling loads and vibration frequencies can be modified by the presence of moisture, temperature or both. Therefore, to utilize the full potential of advanced structures, it will be necessary to analyze the effects of moisture and temperature in composite structural components.

Adams and Miller [1], Ishikawa et al. [2] and Strife and Prewo [3] have studied the effect of environment on the material properties of composite materials. They have observed that the environment has significant effect on strength and stiffness of the composites. Therefore, there is a need to understand the behavior of composite structures subjected to hygrothermal conditions. Whitney and Ashton [4] have used the classical laminate plate theory, neglecting the transverse shear deformation, to study the hygrothermal effects on static and dynamic responses of composite laminated plates using the Ritz method. Pipes et al. [5] have presented the distribution of in-plane stresses through the thickness of symmetric laminates subjected to moisture absorption and desorption. Sereira et al. [6] have presented a hygrothermal analysis of the hybrid composites under the effect of the cyclic environmental conditions by the finite element method. Yifeng and Yu [7] have constructed a hygrothermal elastic model for analyzing composite laminates under both mechanical and hygrothermal loadings by a variational asymptotic method. Upadhyay et al. [8] have presented an analytical solution of nonlinear flexural response of elastically supported cross-ply and angle-ply laminated composite plates under hygrothermal environment.

Many studies, based on classical plate theory, of thin rectangular plates subjected to mechanical or thermal loading or their combinations as well as the hygrothermal effects are available in the literature (Strife and Prewo [3] and Bahrami and Nosier [9]). The classical laminated plate theory and the first-order shear deformation plate theory are typical deformation theories for the analysis of laminated composite plates. Mahato and Maiti [10] have investigated aeroelastic performances of smart composite plates under aerodynamic loads in hygrothermal environment using first-order shear deformation theory. The classical theory neglects the shear stresses while the first order theory assumes a constant transverse shear strain across the thickness direction, and a shear correction factor is generally applied to adjust the transverse shear stiffness for the static and stability analyses. However, some investigations showed that the bending and postbuckling responses of rectangular plates are sensitive to the choice of the shear correction factor.

To avoid the use of shear correction factor, various higher-order theories have been proposed to predict the bending response of rectangular plates. Shen [11] has considered the effects of temperature and moisture on the material properties of laminated plates based on Reddy’s higher-order plate theory (Reddy [12]). Patel et al. [13] have studied the static and dynamic response of the thick laminated composite plates under hygrothermal environment based on a higher-order theory. Singh and Verma [14] have investigated the combined effects of temperature and moisture on the buckling of laminated composite plates with random geometric and material properties using higher-order shear deformation theory. Lo et al. [15] have developed a global-local higher order theory to study the response of laminated plates exposed to hygrothermal environment. Recently, Zenkour [16] has presented a hygrothermal bending analysis for a functionally graded material plate resting on elastic foundations.

2. Formulation of the problem

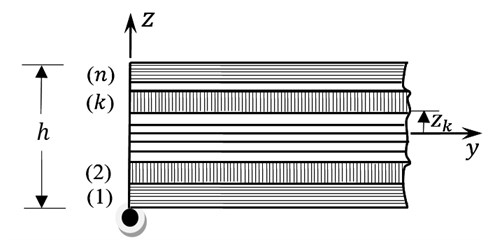

Consider a fiber-reinforced rectangular laminated plate of length a, width b and uniform thickness h (see Fig. 1). The plate composed of n orthotropic layers oriented at angles θ1, θ2, ... θn. The material of each layer is assumed to possess one plane of elastic symmetry parallel to the x-y plane. Perfect bonding between the orthotropic layers and temperature-independent mechanical, thermal and moisture properties are assumed. Let the plate be subjected to a transverse static mechanical load q(x,y) and a temperature field T(x,y,z) as well as a moisture concentration C(x,y,z).

The displacement field at a point in the laminated plate, according to the unified shear-deformable plate theory (Zenkour [17]), is expressed as:

where (ux,uy,uz) are the displacements along x, y, and z directions, respectively; (u,v,w) and (φx,φy) they denote the displacements and rotations of transverse normals on the plane z=0, respectively. The displacement field can be obtained in the case of the classical plate theory (CPT) by setting Ψ(z)=0. The displacement field for the first-order shear deformation plate theory (FPT) is obtained by setting Ψ(z)=0. Whereas in the higher-order shear deformation plate theory (HPT) (see Reddy [18]) we can obtain the displacement field by setting:

Fig. 1Schematic diagram for the cross-ply laminated composite plate

Finally, the displacement field for the sinusoidal shear deformation plate theory (SSPT) (Zenkour [17, 19]) can be obtained by setting:

In the FPT, the in-plane displacements are expanded up to the first term in the thickness coordinate, and the relations of normals to the mid-surface are assumed independent of the transverse deflection. Then the FPT yields a constant value of transverse shearing strain through the thickness of the plate, and thus requires shear correction factors in order to ensure the proper amount of transverse energy. The actual value of shear correction coefficient of the present FPT is 5/6. The forms of the assumed displacement functions for HPT and SSPT are simplified by enforcing traction-free boundary conditions at the top and bottom surfaces of the plate. No shear correction factors are needed in computing the shear stresses for these theories, because a correct representation of the transverse shearing strain is given.

The strains are related to the displacements given in Eq. (1) by the following relations:

where:

Neglecting σz for each layer, the stress-strain relationships, accounting for transverse shear deformation, thermal and moisture effects, in the plate coordinates for the kth layer can be expressed as:

where c(k)ij are the transformed elastic coefficients; ΔT=T-T0, ΔC=C-C0 in which T0 is the reference temperature and C0 is the reference moisture concentration; (αx,αy,αxy) are the thermal expansion coefficients in the plate coordinates and (βx,βy,βxy) are the moisture concentration coefficients in the plate coordinates.

It is to be noted that due to the macroscopic homogeneity of an anisotropic body, any translation in the x, y or z co-ordinate direction inside the body does not alter its elastic characteristics. So, under a general co-ordinate transformation, an initially orthotropic material becomes generally anisotropic. However, there are three specific co-ordinates transformations under which an orthotropic material retains monoclinic symmetry, namely, rotations about the axes x, y or z. For example, if the material is orthotropic with respect to the old co-ordinate system, it follows under rotation through an angle θk about the z-axis that, the transformation formulae for the stiffnesses c(k)ij are of the form (Bogdanovich and Pastore [20]):

where c=cosθk, s=sinθk, and cij, are the plane stress-reduced stiffness of the lamina:

c44=G23,c55=G13,c66=G12,

in which E1 and E2 are Young’s moduli in the x and y material principal directions, respectively; ν12 and ν21 are Poisson’s ratios; and G12, G23 and G13 are shear moduli in the x-y, y-z and x-z plane, respectively.

For both symmetric and anti-symmetric cross-ply laminated plates, thermal expansion coefficient and moisture concentration coefficient vanishes, i.e., αxy=0 and βxy=0. We introduce the following definitions for stress resultants:

(Qxz,Qyz)=∑nk=1zk+1∫zk(τ(k)xz,τ(k)yz)Ψ'(z)dz,

where (Nx,Ny,Nxy) are the stress resultants, (Mx,My,Mxy) are the stress couples, (Sx,Sy,Sxy) are additional stress couples and (Qxz,Qyz) are the transverse shear stress resultants. Note that, zk represents the distance from the mid-plane to the lower surface of the kth layer.

Integrating Eqs. (6) over the thickness, the stress and moment resultants can be related to strains by the following relations:

where the following definitions are used:

NHT={NHTx,NHTy,NHTxy}t,NHT={MHTx,MHTy,MHTxy}t,SHT={SHTx,SHTy,SHTxy}t,

ε={ε0x,ε0y,γ0xy}t,κ={κx,κy,κxy}t,η={ηx,ηy,ηxy}t,

A=[A11A12A16A12A22A26A16A26A66],B=[B11B12B16B12B22B26B16B26B66],D=[D11D12D16D12D22D26D16D26D66],

Ba=[Ba11Ba12Ba16Ba12Ba22Ba26Ba16Ba26Ba66],Da=[Da11Da12Da16Da12Da22Da26Da16Da26Da66],Fa=[Fa11Fa12Fa16Fa12Fa22Fa26Fa16Fa26Fa66],

Q={Qxz,Qyz}t,γ={γ0xz,γ0yz}t,Aa=[Aa44Aa45Aa45Aa55].

Note that the superscript t denotes the transpose of the given vector. The laminate stiffness coefficients Aij, Bij, Dij, Aaij, Baij, Daij and Faij are defined in terms of the reduced stiffness coefficients c(k)ij for the layers k=1,2,…,n as:

{Baij,Daij,Faij}=∑nk=1zk+1∫zkc(k)ijΨ(z)(1,z,Ψ(z))dz,(i,j=1,2,6),

Aaij=∑nk=1zk+1∫zkc(k)ij[Ψ'(z)]2dz,(i,j=4,5).

If the plate construction is cross-ply, i.e., θk should be either 0° or 90°, then the following plate stiffness coefficients are identically zero:

D16=D26=Da16=Da26=0,Fa16=Fa26=0.

In addition, for symmetric cross-ply plates there are four more plate stiffness coefficients equal to zero:

The stress and moment resultants NHTx, NHTy, NHTxy, MHTx, MTHy, MHTxy, SHTx, SHTy and SHTxy due to the hygrothermal loading are defined by:

The temperature variation through the thickness is assumed to be:

where T1, T2 and T3 are thermal loads. Also, the moisture concentration through the thickness is assumed to be:

where C1, C2 and C3 are moisture concentration factors.

3. Governing equations

The governing equations of equilibrium can be derived by using the principle of virtual work:

-∫Ωq(x,y)δwdΩ=0.

By integrating the displacement gradients in Eq. (18) by parts and setting the coefficients of δu, δv, δw, δφx and δφy to zero separately, one can obtain the equilibrium equations associated with the present unified shear deformation theory:

δw:∂2Mx∂x2+2∂2Mxy∂x∂y+∂2My∂y2+q=0,

δφx:∂Sx∂x+∂Sxy∂y-Qxz=0,δφy:∂Sxy∂x+∂Sy∂y-Qyz=0.

Substituting Eqs. (12) into the above equations, one obtains the following operator equation:

where {ˉδ}={u,v,w,φx,φy}t and {f}={f1,f2,f3,f4,f5}t. The elements Lij=Lji of the coefficient matrix [L] and the components of the generalized force vector {f} are defined in Appendix A1.

Let the laminates be simply-supported at the side edges, then the following set of boundary conditions is considered:

u=w=φx=Ny=My=Sy=0,atx=0,b.

It assumed that the applied transverse load q, the transverse temperature loads T1, T2 and T3 and the moisture concentration C1, C2 and C3 can be expressed as:

where λ=iπ/a, μ=jπ/b in which i and j are mode numbers and q0 represents the initial mechanical load.

To solve Eqs. (20) with the boundary conditions given in Eqs. (21), we use Navier’s method which supposing that the displacement component are of the form:

where Uij, Vij, Wij, Xij and Yij are arbitrary parameters. Substituting Eqs. (23) into Eqs. (20), one obtains

where {ˉ∆}={Uij,Vij,Wij,Xij,Yij}t and {F}={Fij1,Fij2,Fij3,Fij4,Fij5}t. The components of the generalized force vector {F} and the elements Cij=Cji of the coefficient matrix [C] are given in Appendix A2.

4. Numerical results

Here we present numerical results for the effect of hygrothermal conditions on symmetric cross-ply laminated plates by using a unified plate theory. The validity of the present theory is demonstrated by comparison between the hygrothermal results and thermal results available in the literature. The improvement in the prediction of displacements and stresses by the present unified theory will be discussed.

Computations were carried out for the fundamental mode (i.e., i=j=1). We will assume in all of the analyzed cases (unless otherwise stated) that a/h=10, a/b=1, and q0=0. All of the lamina are assumed to be of the same thickness and made of the same orthotropic material. The lamina properties are assumed to be:

ν12=0.25,αx=10-6/℃,αy=3×10-6/℃,βx=0,βy=0.44(wt.%H2O)-1.

To illustrate the preceding hygrothermal-structural analysis, a variety of sample problems is considered. For the sake of brevity, linearly varying (across the thickness) temperature distribution ΔT=ˉzT2, non-linearly varying (across the thickness) temperature distribution ΔT=ˉΨ(z)T3 and a combination of both ΔT=ˉzT2+ˉΨ(z)T3 are considered. In addition, only linearly varying (across the thickness) moisture distribution ΔC=ˉzC2 is considered.

Here, the hygrothermal stress and thermal stress problems are treated under a steady state temperature and moisture distribution that is linear with respect to the thickness direction. Different dimensionless quantities are used, at the center of the plate. For pure temperature loading the dimensionless deflection form is ˉw=10wh/(αxˉT2a2). The following dimensionless stresses have been used throughout the tables and figures:

ˉσ5=a2αxˉT2E2h2τxz(0,b2,0),ˉσ6=1αxˉT2E2τxy(0,0,-h2).

Table 1 shows a comparison of the dimensionless center deflections ˉw of three-layer cross-ply (0°/90°/0°) rectangular plates subjected to sinusoidal temperature field linearly varying through the thickness (ˉT3=0) and the center deflections ˉw that is caused by a sinusoidal hygrothermal distribution. The deflections due to the thermal effects are exactly the same as those given in Zenkour [19] and this is not surprise because Zenkour [19] used a similar analysis. However, the hygrothermal effects show a noticeable difference in the deflections and that is due to the existence of moisture concentration. The difference between hygrothermal and thermal effects for all theories are increasing as the aspect ratio increases. The HPT yields results very close to those obtained using SSPT even for thicker plates. Also, the difference between hygrothermal deflections and thermal deflections decreases as the side-to-thickness ratio increases.

Table 1The dimensionless center deflections w- of three-layer (0°/90°/0°) rectangular plates subjected to sinusoidal temperature or hygrothermal distribution* (T-2= 300 °C, T-3=0, C-2= 0.01 %)

a/h | Theory | a/b | ||||

1/3 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | ||

5 | FPT | 1.6324 (1.0998) | 2.1099 (1.1535) | 3.5657 (1.2224) | 3.7212 (1.0157) | 3.0204 (0.7355) |

HPT | 1.6879 (1.1073) | 2.2290 (1.1689) | 3.8261 (1.2452) | 3.9059 (1.0169) | 3.1037 (0.7237) | |

SSPT | 1.6934 (1.1081) | 2.2409 (1.1704) | 3.8499 (1.2472) | 3.9206 (1.0167) | 3.1094 (0.7225) | |

10 | FPT | 1.4178 (1.0701) | 1.6728 (1.0959) | 2.6560 (1.1365) | 3.1090 (0.9972) | 2.7826 (0.7508) |

HPT | 1.4345 (1.0724) | 1.7101 (1.1008) | 2.7623 (1.1463) | 3.2155 (0.9997) | 2.8434 (0.7455) | |

SSPT | 1.4366 (1.0726) | 1.7147 (1.1014) | 2.7749 (1.1475) | 3.2273 (0.9999) | 2.8496 (0.7449) | |

20 | FPT | 1.3591 (1.0619) | 1.5486 (1.0795) | 2.3309 (1.1058) | 2.8121 (0.9883) | 2.6372 (0.7601) |

HPT | 1.3635 (1.0625) | 1.5585 (1.0808) | 2.3616 (1.1087) | 2.8477 (0.9892) | 2.6605 (0.7583) | |

SSPT | 1.3641 (1.0626) | 1.5598 (1.0810) | 2.3654 (1.1090) | 2.8521 (0.9893) | 2.6631 (0.7581) | |

50 | FPT | 1.3423 (1.0596) | 1.5126 (1.0748) | 2.2297 (1.0963) | 2.7078 (0.9851) | 2.5801 (0.7637) |

HPT | 1.3430 (1.0597) | 1.5142 (1.0750) | 2.2348 (1.0967) | 2.7141 (0.9853) | 2.5844 (0.7634) | |

SSPT | 1.3431 (1.0597) | 1.5144 (1.0750) | 2.2355 (1.0968) | 2.7148 (0.9853) | 2.5849 (0.7634) | |

100 | FPT | 1.3399 (1.0593) | 1.5074 (1.0741) | 2.2148 (1.0949) | 2.6919 (0.9847) | 2.5711 (0.7643) |

HPT | 1.3401 (1.0593) | 1.5078 (1.0741) | 2.2161 (1.0950) | 2.6935 (0.9847) | 2.5722 (0.7642) | |

SSPT | 1.3401 (1.0593) | 1.5078 (1.0741) | 2.2163 (1.0950) | 2.6937 (0.9847) | 2.5724 (0.7642) | |

CPT | 1.3391 (1.0592) | 1.5057 (1.0738) | 2.2098 (1.0944) | 2.6866 (0.9845) | 2.5681 (0.7645) | |

*The numbers between parentheses are due to thermal effects according to Zenkour [19] | ||||||

Table 2 shows comparisons for the effect of lamination and thickness on the dimensionless center deflections ˉw of cross-ply square plates subjected to sinusoidal temperature distribution (ˉC2=0) and the effect of lamination and thickness on the dimensionless center deflections ˉw of cross-ply square plates subjected to a sinusoidal hygrothermal distribution (ˉC2=0.01 %). The hygrothermal conditions, affects on the center deflections ˉw more than the thermal one. It is to be noted that, the difference between hygrothermal and thermal results are more for the two-layer cross-ply square plates. For both hygrothermal and thermal effects, it is found that although the use of the shear correction coefficients (5/6) in FPT, the results obtained using HPT and SSPT are more accurate. The deflections obtained for three-layer, symmetric cross-ply (0°/90°/0°) plates are close to those obtained for single-layer (0°) plates.

The effect of shear deformation and aspect ratio on the hygrothermal and thermal response of symmetric four-layer cross-ply (0°/90°/0°) rectangular plates is given in Table 3. For all plate theories the difference between hygrothermal results and thermal results are increasing as the aspect ratio increases for ˉσ1, ˉσ5 and ˉσ6. However, this difference is increasing for ˉσ2 and ˉσ4 as the aspect ratio increases from 0.5 to 1 and then decreases for a/b=2. In addition, the difference between the hygrothermal deflections and thermal deflections are increasing as the aspect ratio increases from 1 to 2 and decreases for a/b=0.5. The square plates give the highest differences between the hygrothermal and thermal results.

Table 2The effect of lamination and thickness on the dimensionless center deflection w- of cross-ply square plates subjected to sinusoidal temperature or hygrothermal distribution (T-2= 300 °C, T-3=0, C-2= 0.01 %)

a/h | Thermal results | Hygrothermal results | ||||||

FPT | HPT | SSPT | FPT | HPT | SSPT | |||

Single-layer (0°) plate | ||||||||

100 | 1.0313 | 1.0313 | 1.0313 | 1.6851 | 1.6851 | 1.6851 | ||

50 | 1.0317 | 1.0317 | 1.0317 | 1.6913 | 1.6913 | 1.6912 | ||

25 | 1.0334 | 1.0334 | 1.0334 | 1.7155 | 1.7155 | 1.7154 | ||

20 | 1.0346 | 1.0346 | 1.0346 | 1.7334 | 1.7333 | 1.7332 | ||

12.5 | 1.0396 | 1.0396 | 1.0396 | 1.8075 | 1.8069 | 1.8067 | ||

10 | 1.0440 | 1.0439 | 1.0438 | 1.8717 | 1.8704 | 1.8699 | ||

6.25 | 1.0602 | 1.0597 | 1.0595 | 2.1100 | 2.1030 | 2.1009 | ||

5 | 1.0721 | 1.0711 | 1.0708 | 2.2859 | 2.2709 | 2.2669 | ||

Two-layer (0°/90°) plate | ||||||||

100 | 1.6765 | 1.6766 | 1.6766 | 7.8238 | 7.8238 | 7.8239 | ||

50 | 1.6765 | 1.6767 | 1.6767 | 7.8238 | 7.8234 | 7.8245 | ||

25 | 1.6765 | 1.6770 | 1.6771 | 7.8238 | 7.8262 | 7.8265 | ||

20 | 1.6765 | 1.6773 | 1.6774 | 7.8238 | 7.8276 | 7.8280 | ||

12.5 | 1.6765 | 1.6786 | 1.6789 | 7.8238 | 7.8335 | 7.8247 | ||

10 | 1.6765 | 1.6798 | 1.6802 | 7.8238 | 7.8390 | 7.8408 | ||

6.25 | 1.6765 | 1.6848 | 1.6858 | 7.8238 | 7.8625 | 7.8672 | ||

5 | 1.6765 | 1.6894 | 1.6910 | 7.8238 | 7.8840 | 7.8913 | ||

Three-layer (0°/90°/0°) plate | ||||||||

100 | 1.0949 | 1.0950 | 1.0950 | 2.2148 | 2.2161 | 2.2163 | ||

50 | 1.0963 | 1.0967 | 1.0968 | 2.2297 | 2.2348 | 2.2355 | ||

25 | 1.1018 | 1.1036 | 1.1039 | 2.2882 | 2.3081 | 2.3106 | ||

20 | 1.1058 | 1.1087 | 1.1090 | 2.3309 | 2.3616 | 2.3654 | ||

12.5 | 1.1224 | 1.1292 | 1.1300 | 2.5067 | 2.5794 | 2.5882 | ||

10 | 1.1365 | 1.1463 | 1.1475 | 2.6560 | 2.7623 | 2.7749 | ||

6.25 | 1.1870 | 1.2057 | 1.2077 | 3.1907 | 3.3989 | 3.4207 | ||

5 | 1.2224 | 1.2452 | 1.2472 | 3.5659 | 3.8261 | 3.8499 | ||

Table 3The results of four-layer (0°/90°/90°/0°) rectangular plates subjected to sinusoidal temperature or hygrothermal distribution* (T-2= 300 °C, T-3=0, C-2= 0.01 %)

a/b | SSPT | HPT | FPT | CPT | |

ˉw | 0.5 | 2.4749 (1.2192) | 2.4653 (1.2178) | 2.3534 (1.2014) | 1.9555 (1.1434) |

1.0 | 4.5182 (1.3601) | 4.4999 (1.3581) | 4.2601 (1.3321) | 3.4609 (1.2445) | |

2.0 | 3.4439 (0.7485) | 3.4415 (0.6488) | 3.3853 (0.7527) | 3.2734 (0.7574) | |

ˉσ1 | 0.5 | 2.6915 (1.6354) | 2.6721 (1.6232) | 2.3921 (1.4469) | 2.5683 (1.5580) |

1.0 | 11.1912 (5.5709) | 11.1352 (5.5409) | 10.1064 (4.9809) | 12.7829 (6.4574) | |

2.0 | –4.0917 (–13.1440) | –4.0732 (-13.1235) | –4.1498 (–12.8312) | –0.5431 (–15.2986) | |

ˉσ2 | 0.5 | 3.0933 (2.0209) | 3.0949 (2.0219) | 3.1040 (2.0279) | 3.2010 (2.0891) |

1.0 | 3.9069 (2.3158) | 3.9174 (2.3218) | 4.0042 (2.3717) | 4.6232 (2.7131) | |

2.0 | 1.1209 (0.2483) | 1.1261 (0.2476) | 1.1788 (0.2322) | 1.4637 (0.0373) | |

ˉσ4 | 0.5 | 6.1278 (3.8852) | 5.9327 (3.7594) | 5.1566 (3.2525) | – |

1.0 | 7.2387 (4.0362) | 7.0185 (3.9089) | 6.1737 (3.4054) | – | |

2.0 | 1.0872 (-0.4806) | 1.0424 (-0.4846) | 0.8380 (–0.5733) | – | |

ˉσ5 | 0.5 | 0.8763 (0.5531) | 0.8298 (0.5237) | 0.5173 (0.3263) | – |

1.0 | 4.1119 (2.2709) | 3.9003 (2.1537) | 2.4695 (1.3621) | – | |

2.0 | 2.1120 (–1.3915) | 2.0088 (–1.3302) | 1.3243 (–0.9060) | – | |

ˉσ6 | 0.5 | 0.3570 (0.3169) | 0.3571 (0.3169) | 0.3637 (0.3209) | 0.3022 (0.2821) |

1.0 | 0.8076 (0.6607) | 0.8069 (0.6603) | 0.8018 (0.6573) | 0.7235 (0.6141) | |

2.0 | 0.9775 (0.7581) | 0.9777 (0.7583) | 0.9775 (0.7602) | 0.9959 (0.7476) | |

*The numbers between parentheses are due to thermal effect according to Zenkour [19] | |||||

For both hygrothermal and thermal effects presented in Table 3 we conclude the following:

(i) The effect of transverse shear deformation must always be incorporated into the analysis, because CPT under-predicts the deflection ˉw and transverse shear stress ˉσ6 and over-predicts the stresses ˉσ1 and ˉσ2 when compared to shear deformation theories.

(ii) The FPT slightly under predicts the deflections and stresses, except ˉσ2, then those obtained using HPT and SSPT. The variation of stresses as per HPT and FPT exhibits a small difference, which increases when the transverse shear stresses ˉσ4 and ˉσ5 are calculated.

(iii) The HPT yields results very close to those obtained using SSPT. When a/b=1, the error predicted by HPT as compared to SSPT are maximum for ˉw and ˉσ6, and minimum for ˉσ1 and ˉσ4. With the increases of a/b ratio, the error increases for ˉσ2 and decreases for ˉσ5.

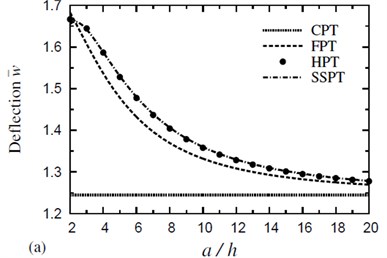

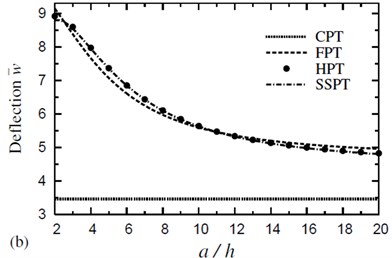

Fig. 2 shows the variation of dimensionless deflection ˉw with the side-to-thickness ratio for symmetric four-layer cross-ply square plates in a thermal and hygorothermal conditions. It is to be noted that the effect of the hygorothermal environment gives deflections greater than the corresponding ones due to thermal response. The deflection due to HPT, SSPT and FPT decreases with increasing the side-to-thickness ratio. The deflection due to CPT has the same value and it shows the lowest sensitivity.

Fig. 2Effect of thickness on the dimensionless deflection w- of a four-layer, symmetric cross-ply (0°/90°/90°/0°) square plate (T-2= 300 °C, T-3=0): a) C-2=0 and b) C-2= 0.01 %

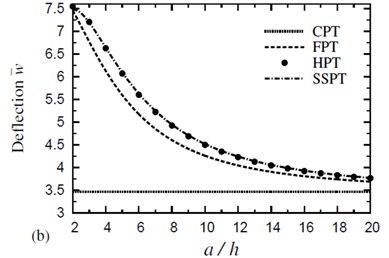

Fig. 3Effect of thickness on the dimensionless deflection w- of a four-layer, symmetric cross-ply (0°/90°/90°/0°) square plate (T-2=T-3= 300 °C): a) C-2=0 and b) C-2= 0.01 %

In Fig. 3, the dimensionless deflection ˉw due to various plate theories is plotted against the side-to-thickness ratio for symmetric four-layer cross-ply square plates in thermal and hygrothermal conditions with ˉT2=ˉT3. Deflections given in the hygrothermal case are greater than the corresponding ones due to thermal one. Fig. 3 reveals that the influence of the thermal load ˉT3 is very sensitive to the variation in the plate thickness. CPT is inaccurate everywhere, even for large values of a/h (i.e., for thin plates).

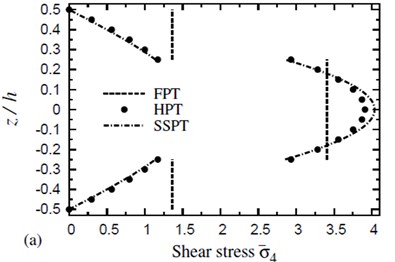

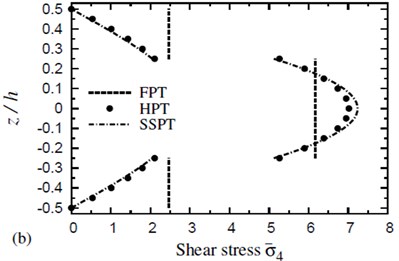

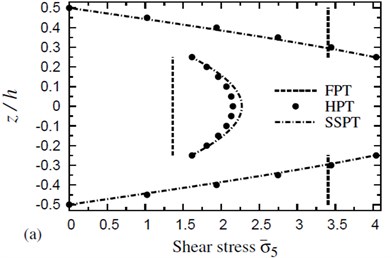

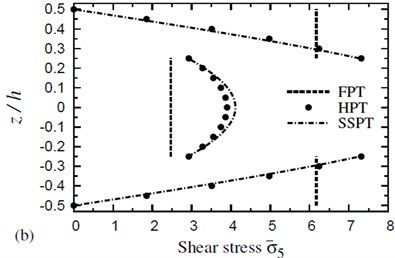

Fig. 4 shows the distribution of transverse shear stress ˉσ4 through the thickness of (0°/90°/90°/0°) cross-ply symmetric square plates due to both thermal and hygrothermal effects. The distribution of transverse shear stress ˉσ5 through the thickness of (0°/90°/90°/0°) cross-ply symmetric square plates due to both thermal and hygrothermal effects is shown in Fig. 5. These figures allow themselves to underline their great influence on transverse shear stresses through-the-thickness of the plate. The results displayed in these figures show that the stress continuity across each layer interface is not imposed in the present theories. The FPT may be insufficient for transverse shear stresses while HPT gives close results to SSPT. The disagreement between HPT and SSPT, especially at the plate center, is owing to the higher-order contributions of SSPT.

Fig. 4The distribution of a transverse shear stress σ-4 through the thickness of a four-layer, symmetric cross-ply (0°/90°/90°/0°) square plate (T-2= 300 °C, T-3=0): a) C-2=0 and b) C-2= 0.001 %

Fig. 5The distribution of a transverse shear stress σ-5 through the thickness of a four-layer, symmetric cross-ply (0°/90°/90°/0°) square plate (T-2= 300 °C, T-3=0): a) C-2=0 and b) C-2= 0.001 %

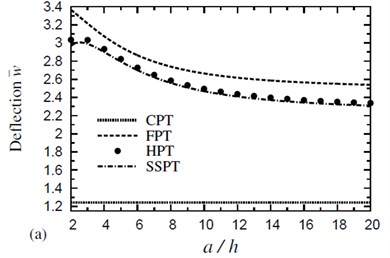

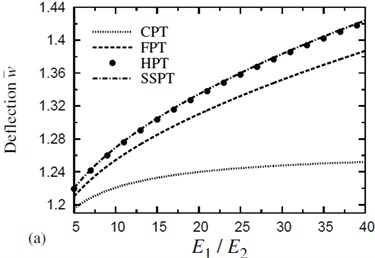

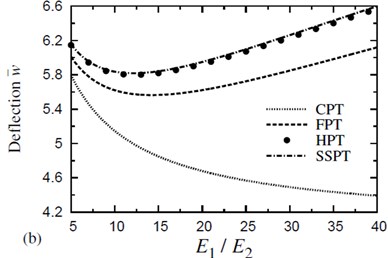

Fig. 6(a) shows the dimensionless deflections ˉw of symmetric four-layer (0°/90°/90°/0°) cross-ply square laminates due to various ratios of the moduli, E1/E2 (for a given thickness, ˉT2=300 °C ˉT3=0, ˉC2=0). It is clear that, CPT under predicts the deflections even at lower ratios of moduli. HPT yields identical deflections to SSPT for all moduli ratios. The difference between SSPT and FPT is, in part. The deflections due to all plate theories are increases as the ratio of E1/E2 increases. The dimensionless deflections ˉw of symmetric four-layer (0°/90°/90°/0°) cross-ply square laminates are compared in Fig. 6(b) for various ratios of the moduli, E1/E2 (for a given thickness, ˉT2=300 °C, ˉT3=0, ˉC2=0.01 %). It is clear that, the severity of shear deformation effects also depends on the material anisotropy of the layer. CPT under predicts the deflections even at lower ratios of moduli and it decreases as the ratio of E1/E2 increases. HPT yields deflections very closed to that of SSPT for all moduli ratios. The difference between SSPT and FPT is, in part, due to the higher-order contributions of the SSPT and the fact that the shear correction factors for FPT depend on the lamina properties and the lamination scheme.

Fig. 6The effect of material anisotropy (E1/E2) on the dimensionless deflection w- of a four-layer, symmetric cross-ply (0°/90°/90°/0°) square plate (T-2= 300 °C, T-3=0): a) C-2=0 and b) C-2= 0.01 %

5. Conclusions

The static response of laminated cross-ply rectangular plates is discussed numerically using a unified theory. The plate is subjected to a sinusoidally non-uniform distribution of temperature and/or a sinusoidally non-uniform distribution of moisture. Non-dimensional deflection and stresses are computed and compared with various plate theories. For the thermal case, we had typical results with those available in the literature and this is no surprise because we used a similar analysis. For the hygrothermal case, it was noted that the difference results in deflection and stresses are significant comparing with the thermal once and this is due to the existence of moisture. In general, it was found that, CPT predicts deflections and stresses significantly different from those of the shear deformation theories. The SSPT and HPT contain the same number of dependent variables as in FPT, but results in more accurate prediction of deflections and stresses, and satisfy the zero tangential traction boundary conditions on the surfaces of the plate. However, both SSPT and HPT do not require the use of shear correction factors. In conclusion, SSPT gives accurate results, especially transverse shear stresses, then other theories including HPT. This is an expected because SSPT is the generalized one.

References

-

Adams D. F., Miller A. K. Hygrothermal micro stress in a unidirectional composite exhibiting inelastic materials behavior. Journal of Composite Materials, Vol. 11, Issue 3, 1977, p. 285-299.

-

Ishikawa T., Koyama K., Kobayayaski S. Thermal expansion coefficients of unidirectional composites. Journal of Composite Materials, Vol. 12, 1978, p. 153-168.

-

Strife J. R., Prewo K. M. The thermal expansion behavior of unidirectional and bidirectional Kevlar/epoxy composites. Journal of Composite Materials, Vol. 13, Issue 4, 1979, p. 264-267.

-

Whitney J. M., Ashton J. E. Effect of environment on the elastic response of layered composite plates. AIAA Journal, Vol. 9, Issue 9, 1971, p. 1708-1713.

-

Pipes R. B., Vinson J. R., Chou T. W. On the hygrothermal response of laminated composite systems. Journal of Composite Materials, Vol. 10, Issue 2, 1976, p. 129-148.

-

Sereira Z., Tounsi A., Adda-Bedia E. A. Effect of the cyclic environmental conditions on the hygrothermal behavior of the symmetric hybrid composites. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, Vol. 13, Issue 3, 2006, p. 237-248.

-

Yifeng Z., Yu W. A variational asymptotic approach for hygrothermal analysis of composite laminates. Composite Structures, Vol. 93, Issue 12, 2011, p. 3229-3238.

-

Upadhyay A. K., Pandey R., Shukla K. K. Nonlinear flexural response of laminated composite plates under hygro-thermo-mechanical loading. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, Vol. 15, Issue 9, 2010, p. 2634-2650.

-

Bahrami A., Nosier, A. Interlaminar hygrothermal stresses in laminated plates. International Journal of Solids and Structures, Vol. 44, Issues 25-26, 2007, p. 8119-8142.

-

Mahato P. K., Maiti D. K. Aeroelastic analysis of smart composite structures in hygro-thermal environment. Composite Structures, Vol. 92, Issue 4, 2010, p. 1027-1038.

-

Shen H. S. Hygrothermal effects on the postbuckling of shear deformable laminated plates. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 43, Issue 5, 2001, p. 1259-1281.

-

Reddy J. N. Mechanics of Laminated Composite Plates. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 1997.

-

Patel B. P., Ganapathi M., Makhecha D. P. Hygrothermal effects on the structural behaviour of thick composite laminates using higher-order theory. Composite Structures, Vol. 56, Issue 1, 2002, p. 25-34.

-

Singh B. N., Verma V. K. Hygrothermal effects on the buckling of laminated composite plates with random geometric and material properties. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites, Vol. 28, Issue 4, 2009, p. 409-427.

-

Lo S. H., Zhen W., Cheung Y. K., Wanji C. Hygrothermal effects on multilayered composite plates using a refined higher order theory. Composite Structures, Vol. 92, Issue 3, 2010, p. 633-646.

-

Zenkour A. M. Hygro-thermo-mechanical effects on FGM plates resting on elastic foundations. Composite Structures, Vol. 93, Issue 1, 2010, p. 234-238.

-

Zenkour A. M. Buckling of fiber-reinforced viscoelastic composite plates using various plate theories. Journal of Engineering Mathematics, Vol. 50, Issue 1, 2004, p. 75-93.

-

Reddy J. N. A simple higher-order theory for laminated composite plates. Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 51, Issue 4, 1984, p. 745-752.

-

Zenkour A. M. Analytical solution for bending of cross-ply laminated plates under thermos-mechanical loading. Composite Structures, Vol. 65, Issues 3-4, 2004, p. 367-379.

-

Bogdanovich A. E., Pastore C. M. Mechanics of Textile and Laminated Composites with Applications to Structural Analysis. Chapman and Hall, New York, 1996.