Abstract

Modal analysis of a flexible, non-rotating rotor with a crack in a shaft is presented. The Jeffcott model of the rotor consists of the massless shaft and a disk concentrating the mass of the full system. The model includes ball bearings supporting the shaft and the model of the transverse shaft crack located near the disk. Simulation results present changes in natural frequencies of the system with the changing angular position of the rotor. Those changes are observed as doubled natural frequency peaks in the rotor’s frequency responses. They appear only for the cracked rotor and can be explained by shaft stiffness changes due to the opening and closing of crack faces under gravity. The results of the conducted numerical analyzes demonstrate that these doubled frequency peaks can be used for early shaft crack detection.

1. Introduction

Frequently used signatures of developing cracks in various mechanical structures are shifts in natural frequencies and changes in mode-shapes of natural vibrations. This is because the crack introduces small local changes in stiffness, which change modal properties of the structure. Those small changes of modal parameters can be detected experimentally by exciting a given structure with a modal hammer and registering its vibration response with an accelerometer. Based on these measurements modal characteristics (natural frequencies and mode-shapes) are evaluated. Such modal approach for damage detection of various mechanical structures is widely reported in the literature.

Nahvi and Jabbari [1] presented analytical and experimental results of modal analysis of cantilever beams. It was observed that the natural frequencies decreased significantly as the crack location moved towards the fixed end of the beam. Dilena and Morassi [2] studied analytically and experimentally the changes in mode-shapes of vibrating thin beams. They confirmed that a crack in a beam shifts the positions of nodal points of vibration modes. The direction by which nodal points shift may be used to estimate the location of damage. Kisa and Gurel [3] used the component mode synthesis technique combined with the finite element method to demonstrate that natural frequencies and mode shapes of a beam depend on the location and depth of cracks. Similar results have been obtained by Viola et al. [4] who conducted experimental and finite element analyses to confirm the shifts in natural frequencies and mode-shapes of natural vibrations of cantilever beams. Gudmundson [5] utilized perturbation methods to calculate variations in natural frequencies due to cracks, notches and other geometrical changes in various mechanical structures. The obtained results were well verified with experiments. A new modeling approach for cantilever beams with cracks has been proposed by Shifrin and Ruotulo [6]. Natural frequencies of a cracked beam were evaluated by representing cracks as massless springs and using a continuous mathematical model of the beam in transverse vibration.

Modal analysis of rotating shafts differs from typical modal analysis of other mechanical structures. The differences are due to additional loadings (gyroscopic moments and Coriolis forces) resulting from the rotational motion of the rotor. Rotating shafts with cracks are even more complicated for analysis as they are described by ordinary differential equations with time-variant coefficients, i.e. by differential equations of the parametric type. Mathematical foundations of the modal analysis of rotating structures have been introduced by Irretier [7]. However, the proposed approach was complicated and not useful for practical applications.

Therefore, Suh et al. [8] suggested a new method of modal analysis of rotating structures with cracks. The method introduces modified coordinates of the rotor by transforming its motion equation with time-variant coefficients into a set of linear differential equations with time-invariant coefficients. Numerical calculations of a flexible, asymmetric rotor confirmed high effectiveness of the method.

Another method of shaft crack diagnosis based on modal analysis has been proposed by Gosiewski and Sawicki [9]. In the method the changes in the system poles are analyzed as results of periodical stiffness changes of a cracked shaft. Locations of the system poles are presented in dependency of the shaft rotating speed. The method is time-effective and does not require expensive force exciters [9].

Modal methods used for cantilever beams can be applied also for crack detection in non-rotating shafts. Thus, changes in natural frequencies and mode-shapes of non-rotating shafts were analyzed and verified experimentally by Dong et al. [10] and Sinou [11].

It should be emphasized that an early shaft crack detection and warning is an important research task. Shafts are used to transfer large amounts of kinetic energy, often are extremely high loaded and rotate with high rotating speeds. Therefore, they should be strong and resilient to various possible damages as well as light and of small diameters. Those opposing, highly demanding requirements expose the shafts to various dangerous failures that can appear as a result of cyclic loading, thermal stresses, creep, corrosion and other factors to which rotating machines are subjected. One of these failures is the transverse shaft crack, which after initiation propagates quickly and can lead to a sudden machine failure, its damage and a serious accident [10].

The most popular modeling approach to rotating machines is known as Jeffcott model of the rotor [12-14]. Chan and Lai [12] presented a detailed analysis of a Jeffcott model of a 250 MW turbine rotor with a cracked shaft. In their analysis they included different depths of the crack, damping coefficients, eccentricity values and rotating speeds of the rotor.

A transverse shaft crack is usually modeled as a local change in the shaft stiffness. This stiffness change is not constant but varies periodically with the rotation of the rotor as a result of a so called crack breathing mechanism. When the rotor rotates, the crack changes its angular position. Then, under the load of external forces applied to the shaft crack faces close and open periodically in accordance to variable stresses appearing at the crack edge.

The current article presents modal analysis of a flexible Jeffcott rotor containing a transverse crack in the shaft. Unlike in the paper by Gosiewski and Sawicki [9], the rotor is not rotating but its angular position changes step by step from 0 to 360°. For those 36 angular positions frequency responses are calculated based on the developed Jeffcott model. It is observed that when angular position of the rotor changes doubled peaks near natural frequencies in the frequency spectra appear. Those doubled peaks are characteristic only for the cracked rotor and can be explained with shaft stiffness changes due to the crack. As a result of those stiffness changes the system poles change their locations which results with doubled frequency peaks in the frequency responses. The obtained numerical results demonstrate that the observed doubled natural frequency peaks can be used for early shaft crack detection.

2. Mathematical model

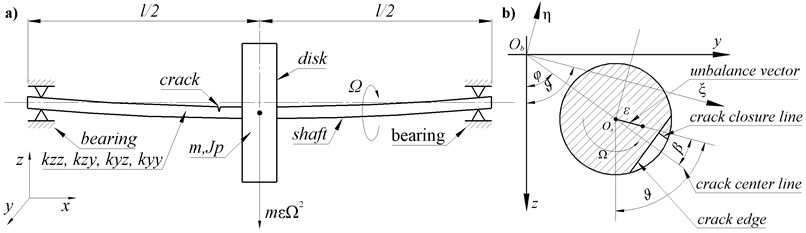

Theoretical analysis has been conducted for Jeffcott mathematical model of the rotor. Jeffcott rotor consists of a massless, flexible shaft and a rigid disk located in the middle of the shaft's length (Fig. 1(a)). The mass of the rotor is concentrated in the disk. The mass center of the disk is shifted by ε from the shaft axis (Fig. 1(b)), simulating the unbalance of the rotor. The rotor is supported by ball bearings of equal stiffness in both horizontal and vertical directions. A transverse shaft crack is located near the disk.

The motion of the rotor is considered in two coordinate systems: global (inertial) coordinate system xyz, and local (rotating) coordinate system ξη. The local coordinate system rotates with the rotor’s rotating speed Ω. While rotating, the ξ axis of the local system remains perpendicular to the crack edge.

The angular position of the unbalance in the local coordinate system is defined with angle β between the crack centerline and the unbalance vector ε (Fig. 1(b)). In the global coordinate system, the position of the unbalance is defined with angle ϑ, where [14]:

Fig. 1Model of the rotor: a) side view and dimensions, b) shaft cross-section at crack location in global and local coordinate systems

It is assumed that the rotor is weight dominant [11, 15-17]. Thus, during the rotation, the breathing behavior of the crack can be simulated with a crack steering function f(φ), depending on the angular position φ of the rotor.

Considering lateral vibrations, the kinetic T and potential U energies of the rotor can be presented as [14]:

where:

Utilizing Lagrange's approach, the following nonlinear differential equations of lateral vibrations of the rotating rotor are obtained:

The uncracked rotor system is symmetric (isotropic), meaning that its stiffnesses in any direction perpendicular to the shaft axis are equal. Consequently, the matrix of lateral stiffness KI is diagonal:

The stiffness matrix of the cracked rotor system is not diagonal and its components change for each angular position of the rotor according to the following equation:

where the first matrix defines the stiffness of the uncracked rotor, and the second – the stiffness reductions Δkξ and Δkη in ξ and η directions, respectively. The function f(φ) is a crack steering function and it depends on the angular position φ of the rotor. According to Mayes and Davies [13, 18, 19] the crack steering function can be presented as:

In the global coordinate system, the stiffness matrix KI of the cracked rotor system can be presented as [14]:

-f(φ)K2[Δk1+Δk2cos(2φ)Δk2sin(2φ)Δk2sin(2φ)Δk1-Δk2cos(2φ)],

where T is the transformation matrix defined with the angular position φ as follows:

Components Δk1 and Δk2 of the stiffness matrix KI are calculated as [14]:

It has been shown [14] that for deep cracks:

which results in:

2.1. Model of the non-rotating rotor

Modal analysis of the cracked rotor is made for the non-rotating Jeffcott rotor. Motion equations of the rotor are obtained from Eqs. (6)-(7) in the following form:

after assuming that ϑ=const, and consequently ˙ϑ=0, ¨ϑ=0.

As can be seen from Eqs. (16)-(17), rotor vibrations in directions y and z are coupled, meaning that the vibrations in z influence the vibrations in y (by the coupling component kzyy in Eq. (16)) and the vibrations in y influence the vibrations in z (by the coupling component kyzz in Eq. (17)). The stiffness coefficients kzy, kyz that couple Eqs. (16)-(17) are non-diagonal components of the stiffness matrix KI (Eq. (11)). It should be noted that kzy, kyz are zero for φ being the multiples of 90°, i.e. for φ=n× 90°, n=0, 1,…. This is because kzy, kyz depend on sin(2φ). Thus, Eqs. (16)-(17) are coupled only for φ≠n× 90° and decoupled for φ=n× 90°.

Eqs. (16)-(17) are linear, time-invariant equations of motion of the non-rotating Jeffcott rotor.

These equations can be transformed to the following state-space model [20]:

where:

C=[01000001],D=[0000],q=[q1q2q3q4]T,u=[FzFy]T,

y=[xzxy]T,q1=˙z,q2=z,q3=˙y,q4=y.

The model given by Eq. (18) has four states q1, ..., q4, two inputs Fz, Fy and two outputs xz, xy. The inputs are external forces Fz, Fy applied to the rotor in directions z and y. The outputs are rotor displacements xz and xy in directions z, y. The system given by Eqs. (16)-(17) defines one natural frequency and one vibrational mode for each axis z and y.

3. Simulation results

Modal analysis of the linear, time-invariant model of the tested rotor, defined by Eqs. (18) has been conducted in Matlab.

The parameters of the rotor are given in Table 1. They have been assumed based on a real rotor system used by Sawicki [14].

The calculations have been conducted for two depths of the shaft crack, defined with two values of the stiffness reduction Δk= 0.10 and Δk= 0.25, where Δk=Δkξ/k.

The results of the modal analysis present natural frequencies ωi of the cracked rotor in dependency of the angular position φ for the non-rotating rotor.

Table 1Parameters of the rotor

Symbol | Physical parameter | Value | Unit |

m | Disk mass | 20 | kg |

k | Shaft stiffness | 8.82×105 | N/m |

ξl | Lateral damping ratio | 0.01 | |

β | Unbalance angle | 0 | deg |

Δk | Stiffness reduction ratio | 0.10,…, 0.25 |

The values ωi of the natural frequencies depend on the locations of the system’s poles si [20]:

where si are zeros of the characteristic polynomial W(s) of the system:

and |si| is the absolute value (modulus) of the complex pole si.

For the rotor system described with Eq. (18) two pairs of complex conjugate poles si, i= 1,…, 4 are obtained from Eq. (20), where s1=s*2 and s3=s*4 (here, the notation s* denotes the conjugate of a complex number s).

For the uncracked rotor, the obtained pole pairs are identical, i.e. s1=s*2, s3=s*4, and s1=s3. Consequently, the system has only one natural frequency ω, which is of the same value for vibrations in both directions z and y, i.e. ω=ω1=⋯=ω4=|s1|=|s3|. This frequency value does not change for different angular positions φ of the rotor.

However, for the cracked rotor, the obtained pole pairs s1=s*2, s3=s*4 change as the angular position φ of the rotor changes, i.e. s1≠s3 for different φ. This is explained in Table 2 where the values of the cracked system poles for selected angular positions are presented.

Table 2Poles and zeros of the cracked rotor system

φ [°] | Δk= 0.10, s1,2, s3,4 | Δk= 0.25, s1,2, ss,4 |

0° | s1,2=2.5±208.23i s3,4=2.5±199.21i | s1,2=2.5±205.56i s3,4=2.5±181.85i |

45° | s1,2=2.5±208.49i s3,4=2.5±200.82i | s1,2=2.5±206.22i s3,4=2.5±186.23i |

90° | s1,2=2.5±209.11i s3,4=2.5±204.67i | s1,2=2.5±207.79i s3,4=2.5±196.42i |

135° | s1,2=2.5±209.73i s3,4=2.5±208.44i | s1,2=2.5±209.34i s3,4=2.5±206.10i |

180° | s1,2=2.5±209.99i s3,4=2.5±209.99i | s1,2=2.5±209.99i s3,4=2.5±209.99i |

225° | s1,2=2.5±209.73i s3,4=2.5±208.44i | s1,2=2.5±209.34i s3,4=2.5±206.10i |

270° | s1,2=2.5±209.11i s3,4=2.5±204.67i | s1,2=2.5±207.79i s3,4=2.5±196.42i |

315° | s1,2=2.5±208.49i s3,4=2.5±200.82i | s1,2=2.5±206.22i s3,4=2.5±186.23i |

Different locations of two conjugate pole pairs result with two natural frequencies of the cracked rotor system ω1,2=|s1|=|s2| and ω3,4=|s3|=|s4|. The first natural frequency ω1,2 is the frequency of natural vibrations in y axis, while the second natural frequency ω3,4 is the frequency of natural vibrations in z axis.

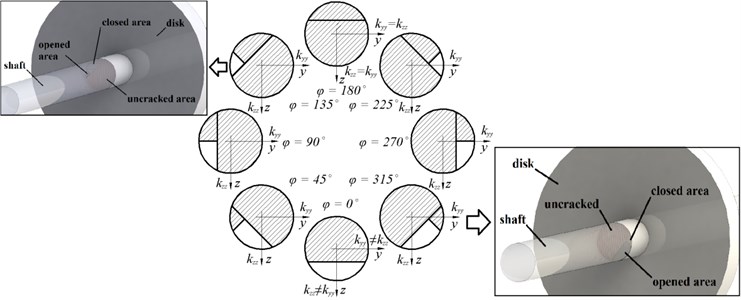

Fig. 2Crack opening and closing for different angular positions φ

The difference in these frequency values can be explained by different stiffness values of the rotor in y and z directions. When the angular position φ changes, the angular position of the crack edge subject to the yz coordinate system also changes (Fig. 2). Consequently, the stiffnesses kyy and kzz in directions y and z also change (see Eq. (11)). As a result the frequency of natural vibrations in y direction becomes different than the frequency in z direction.

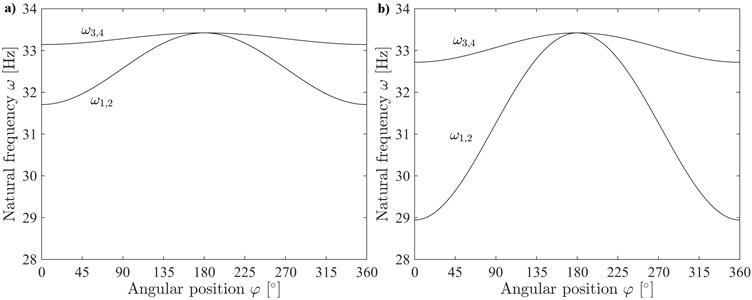

The two natural frequencies ω1,2, ω3,4 of the cracked rotor system are presented in Fig. 3 for a set of angular positions φ.

Fig. 3Natural frequencies ω1,2, ω3,4 of the cracked rotor system for different angular positions φ

The largest difference between ω1,2 and ω3,4 is for φ= 0°. This is the case when the crack edge is perpendicular to z axis and the crack is fully open under the load of the gravity (Fig. 2). It is clear that in this position the smallest stiffness of the shaft is in z direction, while the largest – in y direction. Therefore, the frequency of natural vibrations in z direction ω3,4 becomes smaller than the frequency ω1,2 in y direction.

The difference between ω1,2 and ω3,4 decreases smoothly when φ advances. The crack closes gradually at the same time. The difference becomes zero when φ reaches 180°. In this position the shaft crack is fully closed (Fig. 2) and shaft stiffnesses in both z and y directions become the same. This results in equal values of natural frequencies.

When φ advances further from 180° to 360° the crack opens gradually, which results in the increasing difference between ω1,2 and ω3,4.

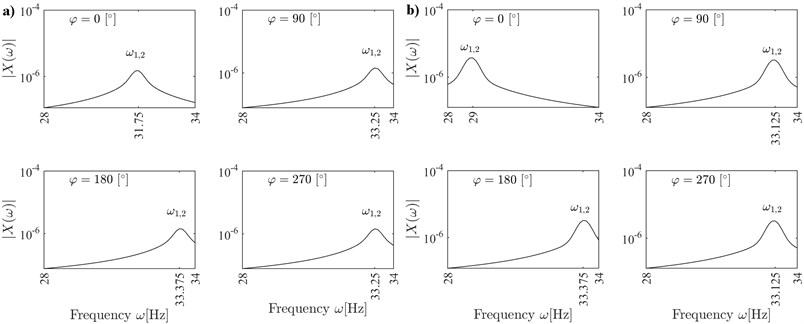

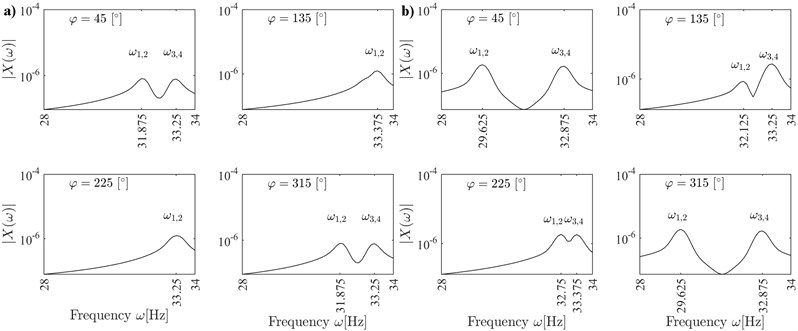

The changes in natural frequencies described above can be observed also in frequency responses presented in Figs. 4, 5. The frequency responses have been obtained by calculating fast Fourier transforms (FFT) of the impulse responses of the rotor. During the simulation the rotor was excited with an impulse-like force Fz and its responses were registered as xz (see Eq. (18)). Then, fast Fourier transforms of the xz signals were calculated.

The frequency responses have been calculated for φ=n×90°, n= 0, 1,… (Fig. 4), and for φ≠n× 90° (Fig. 5) to demonstrate the coupling between vibrations in z and y axes (see the comment below Eqs. (16)-(17)).

If the vibrations of the rotor are coupled (Fig. 5), then two frequency peaks can be observed at natural frequencies ω1,2 and ω3,4 for the vibrations in both z and y axes. The peaks are especially well distinguished for φ= 45° and φ= 315°. If the vibrations of the rotor are decoupled (Fig. 4), then only one frequency peak is observed at the natural frequency ω1,2 for the vibrations in z axis.

The results presented in Figs. 4 and 5 correspond well with the results in Fig. 3 and confirm that at certain angular positions of the cracked rotor the doubled frequency peaks can be observed near natural frequencies in the frequency response.

The changes in natural frequency peaks observed in frequency responses can be used to develop a new shaft crack detection method. The frequency responses can be obtained experimentally by the modal hammer rotor testing. For this testing, an additional accelerometer and a modal hammer should be used to measure the frequency response functions of the rotor. By performing a set of modal hammer tests of a given, non-rotating rotor for several angular positions φ, a set of frequency responses, (similar to those presented in Figs. 4, 5) can be obtained. It is anticipated that by studying these frequency responses the small differences between frequency peaks corresponding to a given natural frequency of the rotor will be observed. As explained above, such doubled frequency peaks appear only in the presence of a shaft crack. However, the proposed concept of the new shaft crack detection method requires experimental verification, which is underway.

Fig. 4Frequency response of the cracked rotor for angular positions φ=n × 90°, n= 0, 1, 2, 3; decoupled vibrations

Fig. 5Frequency responses of the cracked rotor for angular positions φ=n×45°, n= 1, 3, 5, 7; coupled vibrations

4. Conclusions

The article demonstrates that the poles of the rotor system with a cracked shaft change their locations with the changing angular position of the rotor. The crack is modeled as a shaft stiffness reduction in a direction perpendicular to the shaft edge. For different angular positions of the rotor, the shaft crack changes its state gradually from fully open to fully closed. As a result, the stiffness of the shaft in horizontal and vertical directions also changes. Consequently, the locations of the system poles change a little, and the natural frequency peaks at the frequency responses become doubled.

It is anticipated that these doubled natural frequency peaks can be used as signatures of a developing shaft crack. The frequency responses can be obtained experimentally by the modal hammer rotor testing. Further development of the proposed shaft crack detection method requires experimental verification at the test stand.

The application of the presented method to real shaft crack diagnosis problems would require performing the following steps. First the rotor is disassembled from its supporting bearings and then suspended on two thin massless threads, to obtain the free-free mounting. Next, by using a modal hammer, the rotor is impulse-excited at a given shaft axial location and its vibration response is measured by an accelerometer attached to the shaft at other axial location. Impulse responses of the rotor are taken for a set of angle positions of the rotor. Then, the obtained time responses are analyzed using fast Fourier transform and presented in a form of frequency responses shown in Figs. 4, 5. The change of natural frequencies, specifically the appearance of doubled natural frequency peaks, as described in section 3, would indicate a possible shaft crack.

Disassembling the rotor from its supports is rather problematic, therefore the presented method could be applied only at servicing overhauls of a machine. However, the method is simple and even at those rare servicing tests, it is worth using, especially when important rotating machines are to be inspected.

References

-

Nahvi H., Jabbari M. Crack detection in beams using experimental modal data and finite element model. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 47, 2005, p. 1477-1497.

-

Dilena M., Morassi A. Identification of crack location in vibrating beams from changes in node positions. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 255, Issue 5, 2002, p. 915-930.

-

Kisa M., Gurel M. A. Modal analysis of multi-cracked beams with circular cross section. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 73, 2006, p. 963-977.

-

Viola E., Federici L., Nobile L. Detection of crack location using cracked beam element method for structural analysis. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, Vol. 36, 2001, p. 23-35.

-

Gudmundson P. Eigenfrequency changes of structures due to cracks, notches or other geometrical changes. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, Vol. 30, 1982, p. 339-353.

-

Shifrin E., Ruotulo R. Natural frequencies of a beam with an arbitrary number of cracks. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 222, Issue 3, 1999, p. 409-423.

-

Irretier H. Mathematical foundations of experimental modal analysis in rotor dynamics. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 13, Issue 2, 1999, p. 183-191.

-

Suh J. H., Hong S. W., Lee C. W. Modal analysis of asymmetric rotor system with isotropic stator using modulated coordinates. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 284, Issues 3-5, 2005, p. 651-671.

-

Gosiewski Z., Sawicki J. T. A new vibroacoustic method for shaft crack detection. 4th International Symposium on Stability Control of Rotating Machinery ISCORMA-4, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 2007.

-

Dong H. B., Chen X. F., Li B., Qi K. Y., He Z. J. Rotor crack detection based on high-precision modal parameter identification method and wavelet finite element model. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 23, 2009, p. 869-883.

-

Sinou J. J. Effects of a crack on the stability of a non-linear rotor system. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, Vol. 42, 2007, p. 959-972.

-

Chan R. K. C., Lai T. C. Digital simulation of a rotating shaft with a transverse crack. Applied Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 19, 1995, p. 411-420.

-

Gasch R. A survey of the dynamic behaviour of a simple rotating shaft with a transverse crack. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 160, Issue 2, 1993, p. 313-332.

-

Sawicki J. T., Baaklini G. Y., Gyekenyesi A. L. Coupled lateral and torsional vibrations of a cracked rotor. Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2004, Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Vienna, Austria, 2004.

-

Gasch R. Dynamic behaviour of the Laval rotor with a transverse crack. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 22, 2008, p. 790-804.

-

Pu Y. P., Chen J., Zou J., Zhong P. Quasi-periodic vibration of cracked rotor on flexible bearings. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 251, Issue 5, 2002, p. 875-890.

-

Sawicki J. T., Friswell M. I., Kulesza Z., Wroblewski A., Lekki J. D. Detecting cracked rotors using auxiliary harmonic excitation. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 330, 2011, p. 1365-1381.

-

Mayes I. W., Davies W. G. R. A method of calculating the vibrational behavior of coupled rotating shafts containing a transverse crack. IMechE International Conference on Vibrations in Rotating Machinery, Paper C168/76, 1980, p. 53-64.

-

Mayes I. W., Davies W. G. R. Analysis of the response of a multi-rotor-bearing system containing a transverse crack in a rotor. ASME Journal of Vibration, Acoustics, Stress, and Reliability in Design, Vol. 106, 1984, p. 139-145.

-

Ogata K. Modern Control Engineering. Prentice Hall, New York, 2009.