Abstract

As a complicated phenomenon of friction-induced noise, disc brake squeal has remained a challenge to automotive industry. To investigate the intermittent characteristics of disc brake squeal, a three-degree-of-freedom dynamics model considering both the friction coefficient and the disc surface run-out (SRO) is established in this paper. Their influences on system complex eigenvalues and transient responses are numerically investigated. At the same time, an experiment is conducted based on a pin-on-disc setup. The experimental results show that disc brake squeal is mainly dependent on modal coupling, and influenced by the incline angle of disc SRO. When disc brake squeal occurs, the time history of sound pressure is consistent with that of the disc vibration, which is due to the synchronization of the incline angle of macro and micro disc SRO that has the equivalent effect on system stability as friction coefficient does.

1. Introduction

Disc Brake squeal is a noise caused by friction-induced vibration within the frequency range from 1 to 16 kHz. A typical brake squeal sound pressure generally falls into the level of 65-90 dB(A), with its maximum level of 120 dB(A). The analysis of disc brake squeal remains a concern in the circles of the industry and academic studies in that it closely concerns the sound quality of automobiles and passengers’ comfort of driving.

Over the years, researchers have tried great efforts to solve the problem. They have proposed a number of theories concerning the generation mechanism of disc brake squeal, such as the theories of stick-slip, sprag-slip, structure modal coupling etc. [1].

The stick-slip vibration caused by the velocity-dependent friction was once thought to be the main cause of disc brake squeal. Recently, some researchers try to explain the generation mechanism by investigating the instability of multi-degree of freedom (DOF) system incorporating various friction characteristics. Shin proposed a two-mass nonlinear system including in-plane and out-of plane motions [2]. Awrejcewicz built a 2DOF nonlinear system based on the Stribeck friction model. The results of simulation showed that the system was unstable and chaos appeared [3]. Yang put forward a 3DOF non-smooth dynamic system by using the Popp–Stelter friction model, and analyzed its periodic motion, quasi- periodic motion and chaos motion [4]. However, results of the experiments show that even in the condition of drag braking (i.e. when the speed and friction coefficient are kept constant), brake squeal still occurs. Hence, it is inferred that the theory of stick-slip can not satisfactorily account for the phenomenon of brake squeal.

Another theory, the sprag-slip theory, introduced a new concept about generation mechanism of brake squeal from the perspective of system structure. It describes a geometric coupling hypothesis about squeal which occurs even if the friction coefficient remains constant [5]. Sinou built a 2DOF sprag-slip model incorporating nonlinear stiffness, and analyzed the bifurcation behavior by utilizing center manifold theory [6].

Recently, the modal coupling theory has been regarded as one of the most important theories of interpreting the generation mechanism of brake squeal. It introduces the friction force into system equations, which makes the stiffness matrix asymmetric and the system unstable [7, 8]. To analyze the relation between modal coupling and system instability, Hamabe and Hoffmann proposed a single-mass 2DOF model [9, 10]. Popp proposed a single-mass 2DOF model including translation and torsion movements and made inference about the required conditions which may induce the unstability of the system [11]. Rusli put forward a L-shape beam model and applied modal coupling theory to investigate its squeal characteristics [12]. Wagner established a 6DOF model by introducing the gyroscopic force and friction force. The two kinds of forces cause the asymmetricity of both the damping matrix and stiffness matrix, which is possible to cause the system unstable [13]. Ouyang and Mottershead adopted multi-scale method to investigate the nonlinear parameter oscillation of disc under the effect of moving loads [14]. The complex eigenvalue method based on the modal coupling theory has been applied on the investigation of brake squeal, which can interpret many phenomena concerning brake squeal in a certain extent.

In addition, Eriksson, Massi, Hammerström etc. studied the relations of brake squeal to friction surface deformation, roughness and profile, the third body between surfaces, and proposed that there existed dynamic component of friction force which excited the system resonance, and produced the brake squeal [15, 16, 17]. Chen analyzed the squeal generation mechanism of a metal reciprocating sliding test, and reported that the occurrence of squeal was correlated with the roughness of the sliding surface. The essential of the squeal phenomenon lies in the fluctuation of friction force caused by heavy plowing, adhesion and asperities deformation which actually induce squeal generation, also under the effect of elastic features of the friction system [18]. Park developed a 3DOF model incorporating the effects of disc surface run-out (SRO) and velocity-dependent friction coefficient. He concluded that the squeal generation was dependent on the run-out rather than the friction characteristic between the pad and disc [19]. Lee investigated the intermittent characteristic of brake squeal, and inferred that the variation of friction force affected by disc SRO would trigger the vibration and squeal of the system [20]. Vayssière analyzed the influence of the incline angle of disc SRO by utilizing a pin-on-disc tribometer [21]. The previously mentioned studies not only enrich the “Hammering Hypothesis” proposed by Rhee [22], but also develop the friction-induced squeal theories.

In the earlier studies, researchers merely adopted one of the previous theories to analyze the root causes of squeal, which put them in a narrow sense. Recently, more and more evidences show that a single theory can not satisfactorily explain such a complex phenomenon of brake squeal. By synthesizing the triggering mechanism, modal coupling excitation and sound radiation, Chen proposed the Unified Hypotheses [23]. According to the theory, the instantaneous attach-detach process and non-smooth sliding process in the braking process can produce impulsive excitation. When the impulsive excitation is weak while the modal coupling is strong or the vice versa, it is possible for the disc to produce brake squeal. In addition, Chen discussed the modal coupling characteristics of different types of disc brake squeal.

Although great efforts have been made to investigate the problem of brake squeal, it still remained a complicated one due to its relation to many factors, such as structural geometry, friction coefficient, surface topography, temperature, humidity etc. [23]. So far there isn't any theory that can completely account for the events related to disc brake squeal. The current prediction methods are far from satisfactory because they commit overprediction and underprediction [24, 25]. All these facts suggest that more fundamental research and exploiting efforts in this field are needed.

Due to the fact that a disc real brake system is composed of quite many parts, it is rather difficult to investigate the generation mechanism of brake squeal for a real brake system. Many theoretical and experimental researches have been done based on simple apparatus such as pin-on-disc (also called as beam-on-disc) and pad-on-disc systems. Yokoi found that friction-induced squeal would occur when the natural frequencies of beam and disc were very close to each other [26]. Tworzydlo designed a pin-on-disc squeal rig in which the pin was supported elastically. However, the simulated squeal frequency wasn’t consistant with the results of the experiment because the finite element model was simplified [27]. Akay experimented the friction-induced squeal generated in a beam-on-disc setup, and he pointed out that the brake squeal was mainly caused by the concordance of the natural frequencies of the disc and the beam [28].

Tuchinda and Allgaier analyzed that the pin-on-disc system might be unstable and produce squeal noise even when the disc rotated along the inclined pin [29, 30]. Schroth measured the operation deformation shapes of squealing disc by using a 3D laser Doppler vibrometer, and he inferred that squeal was caused by the coupling of in-plane and out-of plane modes [31]. Emira experimented and analyzed the relations of vibration amplitude and sound pressure of beam material, rotation speed and normal load [32]. Giannini proposed that the system instability was influenced by the whole pin-on-disc system according to the results of squeal experiment on pin-on-disc system [33].

Massi and Akay’s squeal experiments of pad-on-disc system showed that the disc dynamics can couple either with the dynamics of the pad or with that of the support, bringing out squeal instabilities in both cases [34, 35]. Based on the squeal experiment results of pad-on-disc system, Mortelette pointed out that when friction coefficient increased, the modes tended to couple and thus squeal was produced [36]. By using a tri-axial force sensor, Beloiu measured the dynamic normal and frictional forces, and computed the dynamic friction coefficient. He found that the three dynamic variables presented periodical characteristics along with intermittent changes of disc SRO [37].

The objective of the present study is to investigate how disc brake squeal would be related to the disc SRO. In section 1, a brief review of the generation mechanism of disc brake squeal is presented. In section 2, a 3DOF friction-induced vibration model of disc brake squeal is proposed to discuss the effect of disc SRO in theory. In section 3, the complex eigenvalue method is utilized to analyze the influences of friction coefficient and incline angle of disc SRO on system instability. In section 4, the transient responses of unstable system with and without disc SRO are compared to analyze the cause of intermittent characteristic of disc brake squeal. In section 5, the validity of theoretical analysis is demonstrated through disc brake squeal tests with a pin-on-disc laboratory setup. Finally, some concluding remarks are presented in section 6.

2. Modeling of disc brake squeal

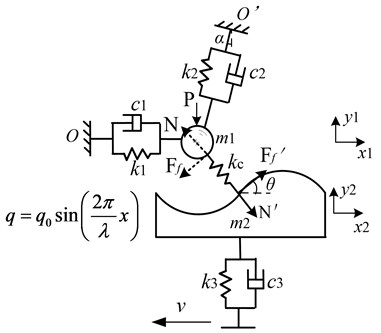

On the basis of the simplified model proposed by Hoffmann [10], a 3DOF model based on pin-on-disc setup is firstly put forward in this paper to investigate friction-induced squeal taking into account the effect of disc SRO, see Fig. 1. is the mass of stationary part (pin) which is subjected to the actions of spring and damping in horizontal direction, spring and damping at an angle to vertical direction, and vertical force . is the mass of moving part (disc) which is subjected to the actions of spring and damping in vertical direction. There exist normal contact stiffness , normal force and frictional force between and that is relatively in movement.

Fig. 13-DOF mechanism model of pin-on-disc brake squeal

Due to the manufacture error, mount misalignment and contact deformation, the disc at a horizontal speed of usually has a SRO value with corresponding incline angle . Though it has been previously stated that according to the sprag-slip theory the system would be unstable if the surface moves toward the inclined bar [5], the pin-on-disc experiment indicates that the system may also be unstable and produce squeal noise if the disc rotates along the inclined pin, which has been verified by Tuchinda’s research [29].

Assume that (1) has motion displacement due to frictional force and is titled by an angle relative to the fixed point . (2) is a constant value for simplification due to the high-frequency and low-amplitude vibration of which affects the angle of a little. (3) Point-to-point contact exists between and . (4) Both the and are subjected to the actions of normal force and frictional force during the friction process. The force on the contact spring is proportional to the displacement between and .

According to the Newton’s second law, the equations of motion for the present model are derived:

where:

Substitute Eq. 2 and Eq. 3 into Eq. 1, and define state vector , the system equations are expressed in the form of state equation:

where:

Obviously, the values of element in the stiffness matrix are changed due to the added items of friction coefficient and of disc SRO, which causes the matrix asymmetry and results in the system instability. The equivalent friction coefficient due to the incline angle of disc SRO is defined as:

Therefore, the total equivalent friction coefficient between pin and disc is:

3. Influence of friction coefficient and SRO on system stability

When studying the stability of dynamic system, the external force is not considered in that the stability is only related to the system itself. In addition, because the damping caused by physical structure is usually very small and has little effect on system stability, it is usually ignored to simplify the calculation. Therefore, the complex dissipative nonhomogeneous matrix differential equation (4) is simplified in a linear form:

According to the complex modal theory [38], when the dynamic equations contain non- proportional damping, asymmetrical damping or asymmetrical stiffness matrixes, the eigenvalue is possible in the form of complex number:

where is the real part of the eigenvalue that corresponds to the damping factor of the system, and is the imaginary part of the eigenvalue that corresponds to the natural frequency of the system. A negative real part indicates that the corresponding mode is stable due to positive damping. In other words, a perturbation about the static equilibrium sliding state will not modify the equilibrium position of the system. A positive real part equivalent to a negative damping leads to an unstable mode. By examining the real part of the system eigenvalues, the modes that are likely to be unstable and produce squeal can be predicted.

In present investigation, the masses of cantileveled pin and disc are weighted, 0.033 kg and 4.35 kg. Although the actual pin and disc may have many order modes and corresponding mode parameters, only several modes related to brake squeal are choosen for analysis in the simulation. The modal test and finite element analysis show that the bending mode frequency of pin 2561 Hz, the tensile mode frequency of pin 8653 Hz, and the out-of-plane mode frequency of disc 2346 Hz. Then the mode stiffness of them are computed according to their modal frequencies, 8.545×106 N/m, 9.755×107 N/m, 9.452×108 N/m. The contact siffness between pin and disc is computed according to the material properties and pin size, 4.632×107 N/m. The friction coefficient 0~0.8, and the incline angle of pin 2o.

The real incline angle of disc SRO is closely related to the wavelength and amplitude of SRO. The inclined angle of SRO in some local contact positions may be large in spite that the amplitude of SRO is very small, which will be discussed in section 5. Here, is taken between the ranges of -8o and 8o to make clear the influence of incline angle. So the equivalent friction coefficient varies between the ranges of -0.14 and +0.14. In order to simplify the calculation, the damping is not considered deliberately in the complex eigenvalue simulation.

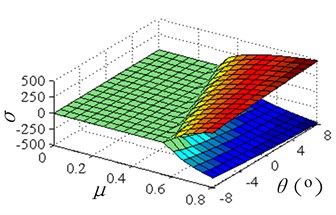

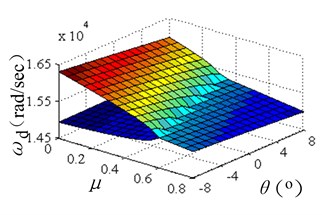

The eigenvalues of Eq. 7 are solved using numerical method with Matlab software. Fig. 2 shows the evolutions of real part and imaginary part of the complex eigenvalue versus friction coefficient and incline angle of disc SRO. As can be seen in Fig. 2(a), the real part surfaces split into two branches as and increased to certain values. One goes towards the positive real part half-space whereas the other branch decreases and remains in the negative real part half-space. Fig. 2(b) shows that the typical lock-in phenomenon between both modes of and as and increased, which means the system is coupled and unstable. The coupled frequency is about 14997-15317 rad/sec (2387-2438 Hz). The complex eigenvalue simulation shows that the incline angle of disc SRO has the equivalent effect on the system stability as the friction coefficient does.

Fig. 2Evolutions of complex eigenvalues versus friction coefficient and incline angle of SRO

a)

b)

4. Influence of disc SRO on transient responses

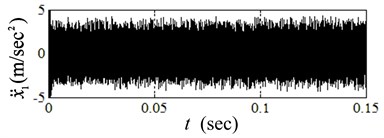

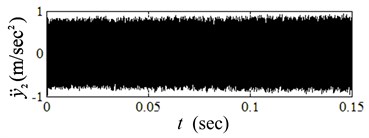

The system transient dynamics under the condition of smooth friction surface is firstly simulated. Take the friction coefficient 0.4, the velocity of 0.02 m/s, the damping coefficient 220 N/m·s-1, and the applied force on 10 N. The time histories of vibration variables of and are shown in Fig. 3.

Both the vibration amplitudes of and are excited to vibrate in a high frequency, which means that the system is unstable and produces self-excited vibration. The vibration frequency is consistent with the coupling frequency of the system.

Fig. 3Transient responses of unstable system when sliding on smooth surface

a)

b)

In order to simplify the analysis of the influence of SRO value on the system responses though it actually varies randomly, is assumed as a sine function in space whose wavelength is and amplitude is :

When the mass moves to the left at a speed of , the SRO of will produce a time-varying sine input signal relative to :

So the relation between that describes the incline angle of SRO and time can be expressed as the following:

According to the transition of SRO from space signal into time signal, we can conclude that the value of is relevant to the wavelength and amplitude . The value of increases as increases and as decreases, or vice versa.

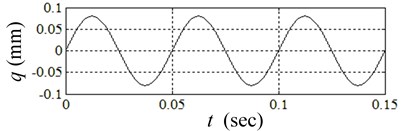

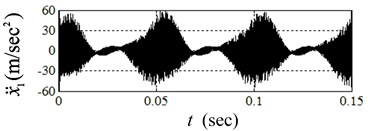

The wavelength of SRO 1 mm, amplitude 0.08 mm are taken for simulation. According to Eq. 11, the maximum incline angle of disc SRO in some local contact positions may even reach 26.7o, and the maximum value of is 0.5. The influence of disc SRO on the responses of vibration variables of and are simulated, see Fig. 4.

As the disc SRO on the rising stage, the responses tend to diverge, i.e. the system is unstable, and thus the friction-induced vibration takes place. The system tends to be convergent and stable when SRO on the descending stage, and the vibration is therefore reduced. The reason is that the incline angle of disc SRO changes the values of and between the surfaces of and , then the system stability is altered accordingly.

The above simulations of friction-induced vibration show that the system stability is mainly dependent upon the modal coupling of the system itself, and is influenced by the incline angle of SRO. The bigger the incline angle of SRO is, the more easily the self-excited vibration occurs, or vice versa. Therefore, the friction-induced vibration happens intermittently due to the influence of disc SRO.

Fig. 4Transient responses of system due to disc SRO

a)

b)

c)

5. Experiments on brake squeal with pin-on-disc setup

5.1. Pin-on-disc setup

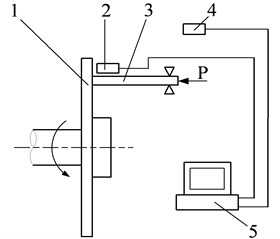

The complicated structure of disc brake system makes the problem of disc brake squeal more difficult to deal with. In this paper, a pin-on-disc brake squeal laboratory device is designed by using a solid brake disc (cast iron, Young’s module 105 GPa, density 7220 kg/m3, Poisson's ratio 0.21) and a round rod (PA6, 30 mm, cantilever length 45 mm, 2.95 Gpa, 1040 kg/m3, 0.35). The schematic diagram and a real photo of the brake squeal test rig are shown in Fig. 5.

The disc 1 is driven by motor and through transmission. The pin 3 is held by a clamp and applied with the axial force . The surface vibration of disc and sound pressure of squeal are respectively measured by an eddy current displacement sensor 2 and a microphone 4, which are connected to a data acquisition system. The sample rate is 40 kHz. In order to minimize the measurement error of the disc surface vibration at the contact position, the non-contact displacement sensor 2 is mounted adjacent to the pin 3 in the same circumference.

Because the disc hat and one end of the pin are mounted in the setup, it is necessary to identify the natural mode shapes and frequencies of pin and disc in constraint conditions. However, it is difficult to extract the required parameters of pin by using experimental modal analysis (EMA) method in that the cantilever length of pin is only 45 mm which is too short to excite the pin vibration by a impulse force hammer. To solve this problem, the natural frequencies of a cantilever beam (550 mm in length) are firstly measured, thus the accurate values of material’s module and Poisson's ratio can be computed on the basis of the relations between material parameters and natural frequencies of such structure. Then, as shown in Table 1, the modal characteristics of constrained pin (45 mm in length) are identified by using finite element analysis (FEA) techniques. In the same table, the modal characteristics of disc under constraint conditions are measured by using EMA method and are also computed by FEA technique for comparison. It can be obviously observed that the measured and simulated frequencies are in good agreement with each other.

Fig. 5The brake squeal test rig: 1 – disc; 2 – eddy current transducer; 3 – pin; 4 – microphone; 5 – data acquisition system

a) The schematic diagram

b) The general view of the experimental setup

Table 1The natural modes and frequencies of constrained pin and disc

Component | Mode shape description | Experiment result (Hz) | FEA result (Hz) | Mode shape |

Pin | Bending | / | 2561 |  |

Torsional+swell | / | 5376 |  | |

Tensile | / | 8653 |  | |

Disc | 1st nodal diameter | 1236 | 1276 |  |

2nd nodal diameter | 1629 | 1610 |  | |

3rd nodal diameter | 2332 | 2346 |  | |

4th nodal diameter | 3620 | 3466 |  |

5.2. Disc brake squeal experiment

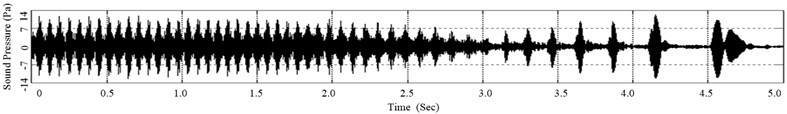

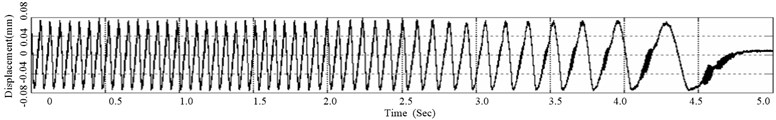

Initially, the disc rotates for about 2 s at a steady speed of 900 rpm while the pin is applied with an axial force of 10 N. Then the motor is powered off to stop the disc. The signals of sound pressure and disc surface vibration during the whole braking process are measured as shown in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7. The disc brake squeal and vibration repeated again and again. The signals in every disc turn behave nearly the same when in brake drag. But during the stopping process, the amplitudes of them firstly decrease and then increase as time evolves. The reason for the phenomena may be the friction coefficient increases as disc rotation speed decreases.

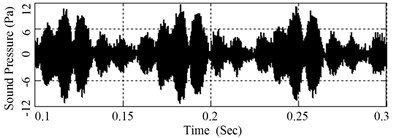

Fig. 6Time history of sound pressure when squeal occurs

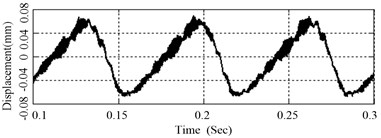

Fig. 7Time history of disc surface vibration signal when squeal occurs

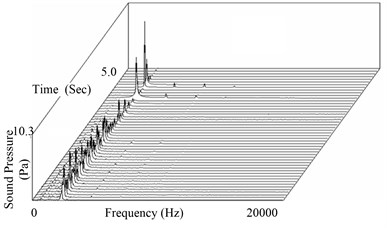

The time-frequency characteristics of disc brake squeal and vibration are given as shown in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9. Both of them are also resemble except that the vibration signal exists low-frequency components. Further analysis shows that the main frequency of disc brake squeal is about 2388 Hz accompanying small amount of harmonic components. Compared with the natural mode shapes and frequencies of disc in constraint conditions, the principal frequency of squeal is close to the 3rd bending mode frequency of disc and the 1st bending mode frequency of round bar.

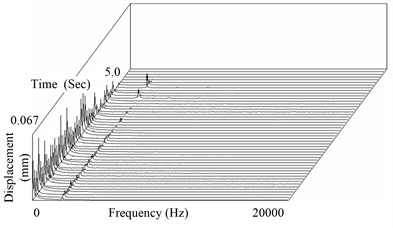

Fig. 8Time-frequency characteristics of sound pressure signal

Fig. 9Time-frequency characteristics of displacement signal

To investigate the influence of disc SRO on brake squeal, the measured signals from 0.1 s to 0.3 s are extracted for analysis, as shown in Fig. 10 and Fig. 11. The time histories of disc brake squeal during three rotations appear intermittently and the amplitudes vary similarly with time.

Due to manufacturing and mounting errors, the brake disc has a certain amount of SRO. There exists a significant signal of high-frequency vibration that is overlaid on the rising stage of SRO while less high-frequency vibration of smaller amplitude on the descending stage.

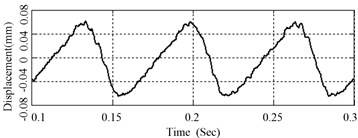

When the signal of Fig. 11 is low-pass filtered to 1000 Hz through a Butterworth filter, the low-frequency component of disc surface character is extracted as shown in Fig. 12. It shows that the disc surface is composed of macro and micro SRO. The macro one has a comparatively longer wavelength and greater amplitude while the micro one has a comparatively shorter wavelength and smaller amplitude. According to Eq. 11, the incline angle of macro SRO is very small due to the long wavelength, but the incline angle of micro SRO may have a great value due to very short wavelength in spite of its small amplitude of SRO.

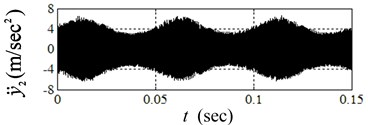

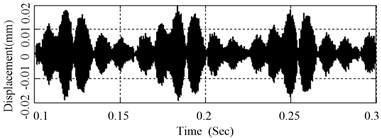

The high-frequency vibration signal of disc surface is extracted through a band-pass filter between 1000 Hz and 2500 Hz, as shown in Fig. 13. It is also similar to the sound pressure, which shows that they have the resemble character.

Fig. 10 to Fig. 13 show that the processes of generation, development and disappearance of disc brake squeal are closely related to the disc SRO. Under the action of friction, the vibration amplitude increases obviously in the rising edge of SRO, and so does the sound pressure of squeal, and vice versa. The main reason is that the incline angle and the equivalent friction coefficient increase when SRO is rising, and the system tends to be unstable and generate friction-induced vibration, and accordingly brake squeal occurs. When disc SRO is descending, and also decrease, and the system tends to be stable. When the friction-induced vibration is suppressed, the squeal of disc is reduced or even disappears.

Fig. 10Sound pressure when squeal occurs

Fig. 11Disc surface vibration

Fig. 12Low-frequency component of disc surface vibration

Fig. 13High-frequency component of disc surface vibration

In addition, the experimental results also show that even when the disc SRO is on the whole rising, there still exists locally descending edge during some regions, which will also suppress the high-frequency vibration. So the squeal will be reduced and even disappear. But squeal may be generated again in the next rising edge of SRO. Regarding this, the friction induced squeal is highly relevant to the value of incline angle of disc SRO.

In short, the synthesis effects of macro and micro SRO may be the cause of intermittent brake squeal, and should be taken into account in analyzing the influence factors on system stability.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a 3-DOF friction-induced vibration model, taking into account the effect of disc SRO, is established to investigate the mechanism of brake squeal and the relations of system stability to modal coupling, friction coefficient and disc SRO.

With the effect of friction, the modal coupling can lead to the stiffness matrix of system asymmetrical and the real part of complex eigenvalue positive, which results in system instability. When friction coefficient increases, the system is eventually coupled to be unstable, and the imaginary part of eigenvalue changes a little due to the decrease of the system stiffness, thus the vibration frequency changes slightly.

There is no direct relation between the system instability and the amplitude of disc SRO, but the incline angle of the disc SRO can affect system stability, as same as that the friction coefficient does. When incline angle increases, the total equivalent friction coefficient increases, and the system tends to be unstable, and the high-frequency coupling vibration will lead to friction-induced squeal, and vice versa.

In the process of disc brake squeal, the squeal is intermittent, and the time history of sound pressure shows the same tendency as those of disc vibration amplitude and velocity. This can be attributed to the synchronization of macro and micro disc SRO that has the equivalent effect on system stability as friction coefficient does.

References

-

Kinkaid N. M., O'Reilly O. M., Papadopoulos P. Automotive disc brake squeal. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 267, Issue 1, 2003, p. 105-166.

-

Shin K., Brennan M. J., Joe Y.-G., Oh J.-E. Simple models to investigate the effect of velocity dependent friction on the disc brake squeal noise. International Journal of Automotive Technology, Vol. 5, Issue 1, 2004, p. 61-67.

-

Awrejcewicz J., Olejnik P. Friction pair modeling by a 2-dof system: numerical and experimental investigations. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos, Vol. 15, Issue 6, 2005, p. 1931-1944.

-

Yang F.-H., Zhang W., Wang J. Sliding bifurcations and chaos induced by dry friction in a braking system. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, Vol. 40, Issue 3, 2009, p. 1060-1075.

-

Spurr R. T. A theory of brake squeal. Proceedings of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers (Automotive Division), 1961, Issue 1, p. 33-40.

-

Sinou J. -J., Thouverez F., Jezequel L. Analysis of friction and instability by the centre manifold theory for a non-linear sprag-slip model. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 265, Issue 3, 2003, p. 527-559.

-

North M. R. Disc brake squeal. IMechE Conference on Braking of Road Vehicles, London, England, 1976, C38/76, p. 169-176.

-

Liles G. D. Analysis of disc brake squeal using finite element methods. SAE Paper 891150.

-

Hamabe T., Yamazaki I., Yamada K., Matsui H., Nakagawa S., Kawamura M. Study of a method for reducing drum brake squeal. SAE Paper 990144.

-

Hoffmann N., Fischer M., Allgaier R., Gaul L. A minimal model for studying properties of the mode-coupling type instability in friction induced oscillations. Mechanics Research Communications, Vol. 29, Issue 4, 2002, p. 197-205.

-

Popp K., Rudolph M., Kröger M., Lindner M. Mechanisms to generate and to avoid friction induced vibrations. VDI-Berichte, Issue 1736, 2002, p. 1-15.

-

Rusli M., Okuma M. Squeal noise prediction in dry contact sliding systems by means of experimental spatial matrix identification. Journal of System Design and Dynamics, Vol. 2, Issue 2, 2008, p. 585-595.

-

Wagner U. V., Schlagner S. On the origin of disk brake squeal. International Journal of Vehicle Design, Vol. 51, Issue 1/2, 2009, p. 223-237.

-

Ouyang H.-J., Mottershead J. E. Optimal suppression of parametric vibration in discs under rotating frictional loads. Proceedings of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 215, Issue 1, 2001, p. 65-75.

-

Eriksson M., Bergman F., Jacobson S. On the nature of tribological contact in automotive brakes. Wear, Vol. 252, Issue 1-2, 2002, p. 26-36.

-

Massi F., Berthier Y., Baillet L. Contact surface topography and system dynamics of brake squeal. Wear, Vol. 265, Issue 11-12, 2008, p. 1784-1792.

-

Hammerström L., Jacobson S. Surface modification of brake discs to reduce squeal problems. Wear, Vol. 261, Issue 11, 2006, p. 53-57.

-

Chen G.-X., Zhou Z.-R. Experimental observation of the initiation process of friction-induced vibration under reciprocating sliding conditions. Wear, Vol. 259, Issue 1-6, 2005, p. 277-281.

-

Park P.-J., Choi S.-Y. Brake squeal noise due to disc run-out. Proceedings of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers. Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering, Vol. 221, Issue 7, 2007, p. 811-821.

-

Lee L., Gesch E. Discussions on squeal triggering mechanisms – a look beyond structural stability. SAE Paper 2009-01-3012.

-

Vayssière C., Baillet L., Linck V. Influence of contact geometry and third body on squeal initiation: experimental and numerical studies. Proceedings of World Tribology Congress III, Paper Number: 63839, 2005.

-

Rhee S. K., Tsang P. H. S., Wang Y. S. Friction-induced noise and vibration of disc brakes. Wear, Vol. 133, Issue 1, 1989, p. 39-45.

-

Chen F. Automotive disk brake squeal: an overview. International Journal of Vehicle Design, Vol. 51, Issue 1/2, 2009, p. 39-72.

-

Ouyang H.-J., Nack W., Yuan Y., Chen F. Numerical analysis of automotive disc brake squeal: a review. International Journal of Vehicle Noise and Vibration, Vol. 1, Issue 3/4, 2005, p. 207-231.

-

Chen G.-X., Dai H., Zhou Z.-R. Comparative study on the complex eigenvalue prediction of brake squeal by two infinite element modeling approaches. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 23, Issue 1, 2010, p. 383-390.

-

Yokoi M., Nakai M. Squeals induced by dry friction. Proceedings of Inter-Noise 95, Newport Beach, USA, 1995, p. 155-158.

-

Tworzydlo W. W., Hamzeh O. N., Zaton W., Judek T. J. Friction-induced oscillations of a pin-on-disk slider: analytical and experimental studies. Wear, Vol. 236, Issue 1, 1999, p. 9-23.

-

Akay A. Acoustics of friction. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 111, Issue 4, 2002, p. 1525-1548.

-

Tuchinda A., Hoffman N. P., Ewins D. J. Effect of pin finite width on instability of pin-on-disc systems. Proceedings of IMAC-XX in the International Modal Analysis Conference, Los Angeles, USA, 2002, p. 552-557.

-

Allgaier R., Gaul L., Keiper W., Willner K., Hoffman N. P. A study on brake squeal using a beam-on-disc model. Proceedings of IMAC XX in the International Modal Analysis Conference, Los Angeles, USA, 2002, p. 528-534.

-

Schroth R., Hoffmann N., Swift R. Mechanism of brake squeal – from theory to experimentally measured modal coupling. Proceedings of IMAC XXII, Paper number 370, Dearborn, USA, 2004.

-

Emira N. A., Mohamad H. T., Tahat M. S. Stick-slip detection through measurement of near field noise. Journal of Mechanical Engineering Research, Vol. 3, Issue 3, 2011, p. 96-102.

-

Giannini O., Akay A., Xu Z. A laboratory brake for the study of automotive brake noise. Proceedings of IMAC XX in the International Modal Analysis Conference, Los Angeles, USA, 2002, p. 548-551.

-

Massi F., Giannini O., Baillet L. Brake squeal as dynamic instability: an experimental investigation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 120, Issue 3, 2006, p. 1388-1398.

-

Akay A., Giannini O., Massi F., Sestieri A. Disc brake squeal characterization through simplified test rigs. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 23, Issue 8, 2009, p. 2590-2607.

-

Mortelette L., Brunel J. F., Boidin X., Desplanques Y., Dufrénoy P., Smeets L. Impact of mineral fibres on brake squeal occurrences. SAE Paper 2009-01-3050.

-

Beloiu D. M., Ibrahim R. A. Analytical and experimental investigations of disc brake noise using the frequency-time domain. Structural Control and Health Monitoring, Vol. 13, Issue 1, 2006, p. 277-300.

-

Heylen W., Lammens S., Sas P. Modal Analysis Theory and Testing. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, 1999.

About this article

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by National Program on Key Basic Research Project (973 Program, No. 2011CB711200) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51175380).