Abstract

In certain industrial applications with frictional interfaces such as brake systems, the friction-induced vibrations created by coupled modes can lead to a dynamic instability and thus to an important deterioration in the operating condition. As a result, they are considered as a source of critical engineering problem. In addition, the presence of the nonlinearity makes necessary the consideration of the nonlinear dynamic analysis in order to explain clearly the complexity of the contribution of different frequency components due to unstable modes in the self-excited friction-induced vibrations, to get a design as reliable as possible and to avoid catastrophic failure during the operation phase of the mechanism. The present paper is based on previous works of Sinou and Jézéquel and extends them to include a developed damped four-degree-of-freedom system with frictional contact and spring cubic nonlinearities. Its essential goals are to analyze numerically the mode-coupling instability of the four-degree-of-freedom system owing to the friction between the surfaces of contact and to predict its nonlinear dynamic behavior. The numerical study of stability for the static solution of the mechanical system is performed by applying the complex eigenvalue analysis of the linearized differential equations of motion and by identifying the Hopf bifurcation points as a function of the coefficient of kinetic friction. Depending on the Runge-Kutta time-step integration scheme and the fast Fourier transforms, quantitative and qualitative nonlinear phenomena related to self-excited friction-induced oscillations and limit cycle evolutions are observed and discussed for various friction coefficients.

1. Introduction

Squeal events of brake systems are deeply relevant to the dry friction between the surfaces of the disk and the pads. This frictional contact can generate the mode-coupling phenomenon which is responsible for flutter instabilities and complex nonlinear self-excited vibrations generally associated with the fundamental frequencies of the system. The instabilities and the self-excited vibrations are recognized as one of the most serious problems of the modern engineering industries. The addition of damping to one part of a brake system (such as the pads) is commonly taken into account to reduce the self-excited friction-induced vibrations and to eliminate the instability. Nevertheless, the presence of excessive damping can have a negative effect and cause instabilities as demonstrated experimentally and numerically (see Earles and Chambers [1] as well as Kinkaid et al. [2]).

Some papers focused on studying simplified and minimal models of mode-coupling mechanisms with frictional contact. In order to provide an overall review of the dynamic behavior of mechanisms with coalescence patterns and frictional interfaces, Ibrahim [3] and Kinkaid et al. [2] presented the studies existing in the literature until the years 1994 and 2002 respectively and including practical dynamic models (such as disk brake systems modeled as a mass-spring system sliding on a running belt) and deterministic investigations as well as few stochastic treatments. Hoffmann and Gaul [4] clarified the influence of structural damping (assumed as linear viscous) on the mode-coupling instability in friction-induced oscillations. The outcomes of their research confirmed that the role of damping may not be considered as an easily ignorable side effect and that the increase of damping could destabilize the investigated minimal dynamic system with sliding friction. Sinou and Jézéquel [5] investigated the dynamics of a two-degree-of-freedom minimal model, analyzed its mode-coupling instability and developed analytical expressions to examine carefully and to understand better the roles of structural damping in the determination of stable and unstable regions. As shown in their article, the damping ratio of the coupled modes has played a key role for eliminating the dynamic instability phenomenon. Sinou et al. [6] introduced the robust damping factor to define the robust stable mechanical system versus the structural damping factor of the stable and unstable modes. This criterion is a function of the differences between the real parts and imaginary parts of the stable and unstable modes. Using the same model as indicated in [5], Sinou and Jézéquel [7] demonstrated that increasing the cubic nonlinearity may decrease the limit cycle amplitudes and that the structural damping ratio between the stable and unstable modes and the nonlinearity were very important and should be taken into account to realize a complete design containing not only the evolution of stable and unstable zones but also the evolution of limit cycle amplitudes as a function of the structural damping and the nonlinear feature of the system.

In many works, authors analyzed the deterministic dynamic behavior of industrial brake systems and obtained numerical and experimental results. Fritz et al. [8] assessed the modal behavior of a brake system with the finite element method and analyzed its squeal as a mode-coupling phenomenon induced by the frictional interfaces. Coalescence patterns describing the evolution of eigenvalues with respect to the coefficient of friction was determined. According to their work, the damping stabilized the system for the case of equally damped modes involved in the coalescence, while it could destabilize the system for other cases of modes. The robust damping factor was used to predict the most stable combination of damping. Sinou and Jézéquel [9] used a dynamic model describing elementary mechanisms of friction-induced vibrations due to a geometric constraint to investigate the effects of damping on flutter instability. During the computational simulations, they found a certain damping factor which allowed obtaining the largest stable region with regard to the effects of damping. Chevillot et al. [10] presented a nonlinear model for the analysis of friction-induced mode-coupling instabilities of an aircraft brake system and developed it using experimental observations to reproduce whirl and squeal instabilities. Parametric studies were performed to determine the effects of damping on the stability. It has been established that the use of a robust damping factor stabilized the system and no destabilization due to damping was possible. The paper of Butlin and Woodhouse [11] bridged the gap between reduced-order models and those of greater complexity by deriving a reliable minimal model. Their method has been shown to be effective and could prove to be more widely applicable. Kang et al. [12] used the single-doublet mode model for stationary or gyroscopic frictional mode-couplings. The stationary frictional mode-coupling generated the mode-merging type instability found to be the substantial brake squeal mechanism, while the gyroscopic frictional mode-coupling made the supplementary influence on the mode-coupling destabilization. The numerical results of their comprehensive model showed a speed corresponding to maximum squeal tendency for each flutter mode. Sinou [13] developed a nonlinear model of a disk brake system to study nonlinear transient and stationary self-excited vibrations. The technique called “continuous wavelet transform” was used to determine the different fundamental frequencies and the combination of their harmonics forming the nonlinear vibrations. From his study, during the occurrence of two instabilities, the transient and stationary vibrations are composed not only of the fundamental frequencies but also of the harmonic components and their combination. Cantone and Massi [14] investigated numerically the squeal instability of a brake system. The results achieved in their work confirmed the theoretical study of Sinou and Jézéquel [5] and allowed standardizing the damping distribution over the full system in order to realize a reduction of the instability zone. Teoh et al. [15] developed a nonlinear two-degree-of-freedom model of a drum brake system and verified it experimentally. As shown in their work, the increase of the friction coefficient decreased the critical value of sliding velocity, while the increase of the braking load increased it and affected the limit cycle of the nonlinear vibrations. The comparison between the numerical and experimental results gave differences smaller than 10 % and the model was greatly associated with the actual system. The numerical analysis of Brunetti et al. [16] showed a good agreement between results from the linear complex eigenvalue analysis and the nonlinear transient analysis for brake squeal and presented the effects of the nonlinearities on the limit cycles. A comparison between the numerical results and the experiments highlighted the main role of the material damping in the dynamic response of the brake system.

Although the reports cited above have treated the problems of mode-coupling instability and self-excited friction-induced vibrations using experimental, analytical and numerical approaches, they always have concentrated on the discussion of classical phenomena observed in the mode-coupling mechanisms with frictional interfaces. There are still phenomena which can be explored in order to understand better the role of coalescence patterns in the dynamics of such mechanical systems. The current research completes the works of Sinou and Jézéquel [5, 7] and extends them to highlight a developed Hultén model which is a damped minimal discrete system (built with four degrees-of-freedom) with frictional contact and spring cubic nonlinearities. Its main aims are to observe new phenomena by evaluating numerically the mode-coupling instability of the four-degree-of-freedom system because of the friction between the surfaces of contact and by investigating its nonlinear dynamic behavior. The nonlinear differential equations of vibratory motion of the adopted mechanism are deduced from Newton’s second law of motion. In the presented numerical examples, three different configurations of the developed Hultén model are studied. The numerical analysis of stability for the static solution of the mechanical system is achieved by computing the eigenvalues of the linearized differential equations of motion and by seeking the Hopf bifurcation points as a function of the coefficient of kinetic friction between the surfaces of contact. The exploitation of the explicit Runge-Kutta time-step integration algorithm permits one to calculate the self-excited friction-induced oscillations and the limit cycle evolutions and to examine and discuss quantitative and qualitative nonlinear phenomena. The fast Fourier transforms are employed to determine the different frequency components contained in the nonlinear oscillations and to interpret the associated dynamic behaviors for diverse coefficients of friction.

2. Model presentation and dynamic analysis

2.1. Description of the proposed mechanical system and equations of motion

In order to analyze flutter instabilities and squeal vibrations in drum brakes, a simplified discrete self-excited model was originally proposed by Hultén [17]. Even if this minimal two-degree-of-freedom model does not attempt to hold all the geometric properties of any realistic system with frictional interfaces, it was used by a lot of researchers [5, 7, 18-20] due to its simplicity and due to the fact that it allows to explore the basic roles of diverse physical parameters in the stability analysis of the static equilibrium points, in the nonlinear dynamic behavior and in the associated limit cycle amplitudes.

The simplified Hultén system consists of a block connected to a moving belt by means of two dampers and two plates supported by two different elastic springs (whose one has a cubic nonlinearity). Considering the frictional forces which are tangential forces between the two plates and the belt, Coulomb’s law of dry friction is assumed to be valid and is expressed as , i.e., the frictional force is proportional to the coefficient of kinetic friction and to the normal force acting on the surfaces of contact. The following assumptions are adopted in the Hultén model for the sake of simplicity:

• the surfaces of the plates and belt are permanently in contact (because of a preload applied to the system) in order to recognize the fundamental features of the mode-coupling mechanism,

• the coefficient of friction between the surfaces of contact is constant,

• the normal forces given by Coulomb’s law are the elastic restoring forces of the springs supporting the plates,

• the belt runs at a constant speed,

• the directions of the frictional forces do not change since the relative velocities between the velocity components of the block and the speed of the belt are considered to be positive.

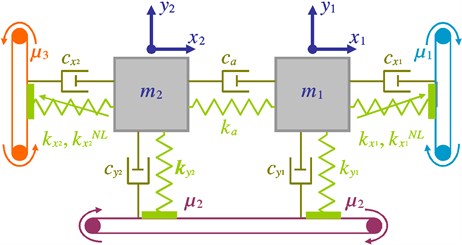

Let Fig. 1(a) sketch a developed Hultén model to be used in what follows. This nonlinear theoretical mechanism is composed of two different simplified Hultén systems linearly coupled through a damper and an elastic spring whose damping and stiffness coefficients are and respectively. Two principal Cartesian fixed frames of reference and shown in Fig. 1(a) are introduced to describe the movement of the mechanism. Namely, the latter includes four degrees-of-freedom. Moreover, it uses three different coefficients of kinetic friction between the plates and the belt, i.e., , and are not identical. All the assumptions mentioned above are taken into account in order to predict the mode-coupling instability in the considered damped mechanical system and to investigate nonlinear phenomena linked with self-excited friction-induced vibrations of this mechanism.

Fig. 1a) Developed Hultén model, b) corresponding free-body diagrams

a)

b)

The system motion and thereby the origin of the displacement measurement are here reported relative to the static equilibrium position corresponding to the quantities , , and . As the weights of the blocks contribute only to the static equilibrium, their effect on the motion is not taken into consideration. The forces exerted on the first block (i.e., the restoring, damping and frictional forces) are represented graphically on the free-body diagram, see Fig. 1(b). Using the data shown on the free-body diagram and by applying Newton's second law of motion to the first block of mass along the and axes when it moves out of equilibrium, Eqs. (1) and (2) are obtained as follows:

where , , and are respectively the linear damping and stiffness coefficients of the horizontal and vertical dampers and springs attached to the first block, is the cubic nonlinear stiffness coefficient of the horizontal spring. The dot refers to the differentiation with respect to time .

Drawing the free-body diagram for the second block provides a simplified graphical representation for all the applied forces, see Fig. 1(b). When the second block of mass is displaced by the amounts and from the static equilibrium position, the utilization of Newton’s second law of motion can yield the two following differential equations:

where , , and are respectively the linear damping and stiffness coefficients of the horizontal and vertical dampers and springs attached to the second block, is the cubic nonlinear stiffness coefficient of the horizontal spring.

Considering Eqs. (1)-(4), the obtained nonlinear second-order differential equations describing the dynamic behavior of the developed Hultén system can be written with respect to the chosen inertial frames of reference in the following matrix form:

with:

where , and are the global displacement, velocity and acceleration vectors of the considered mode-coupling mechanism. , and are the global mass, damping and stiffness matrices with constant coefficients. It can be noted that the mass and damping matrices are symmetric, while the stiffness matrix is non-symmetric due to the fact that the frictional forces have been taken into account in the system being studied. Lastly, is the global external nonlinear force vector including the excitations due to the influence of the spring cubic nonlinearities as well as to that of the friction between the surfaces of contact.

2.2. Prediction of the stability and the nonlinear dynamic behavior

In this section, the treatment of the equations of motion is detailed. The system of nonlinear differential equations (see Eq. (5)) including constant matrices is transformed into a first-order differential equation by introducing the state-space vector , i.e.:

with

where is the identity matrix of dimensions 4×4. As already stated above, the equations of motion are nonlinear. This is due to the nonlinear force vector and thereby to the cubic nonlinearity of the horizontal springs (local components) even if it does not concern all the degrees-of-freedom of the mechanism. For a nonlinear differential system with constant coefficients, the stability of a static equilibrium point is evaluated using the complex eigenvalue analysis of the system linearized at the static equilibrium point which can be obtained by solving the nonlinear static equations as reported in [21]. Therefore, a consistent linearization of the nonlinear force vector is applied by building a first-order Taylor series expansion of this vector in the vicinity of the static position , then:

with . According to Eq. (12), the static force vector and the derivative of the nonlinear force vector with respect to the displacement vector are related only to the static equilibrium position . Substituting Eq. (12) into Eq. (5), the equations of motion of the mode-coupling mechanism become linear as follows:

For the nonlinear mechanical system under study, the static equilibrium point corresponds to , , and as explained in the previous section (to the displacement vector ), i.e., the physical static solution coincides with the origin of the system. Since the displacement vector corresponding to the static solution is nil, the components of the static force vector and the matrix are equal to zero. Thus Eq. (13) becomes:

In this case, the vector expresses a small perturbation about the equilibrium point . Due to the linearization of the force vector , the left-hand side of Eq. (5) is never modified, while its right-hand side turns into a nil amount. As a consequence, the state-space system presented in Eq. (10) has a homogeneous form (differential system with no external forces) and can be rewritten in Eq. (15):

Then, the eigenvalues of the matrix of the homogeneous state-space system (Eq. (15)) are calculated in order to predict the stability of the static equilibrium point and to seek the natural (fundamental) frequencies of the mode-coupling mechanism. They are generally pairs of complex conjugate solutions. For each pair, the solutions have the same modulus and are written in the following form:

with . , and (, the number of degrees-of-freedom is 4) are respectively the eigenvalues, the corresponding real parts as well as the natural frequencies of the stable and unstable modes of the linearized system. Because of the non-symmetric stiffness matrix (as a result of the presence of friction contribution), the proposed four-degree-of-freedom model can be unstable. The criterion stipulates that the static equilibrium point (or the linear differential system) is asymptotically stable if the real part of all the eigenvalues is less than or equal to zero, while it is unstable if the real part of at least one of the eigenvalues is greater than zero. Considering the coefficient of friction as a control parameter, the Hopf bifurcation points corresponding to the generation of instability are determined by:

where is the coefficient of friction at which the instability begins to occur (because the complex eigenvalues have at least one positive real part) and the Hopf bifurcation appears. Thus, the real parts of the eigenvalues and the associated natural frequencies relative to stable and unstable modes are described versus the control parameter .

Now, it is well known that the stability analysis about a static equilibrium point may lead to an under-estimation or an over-estimation of the unstable modes observed in the nonlinear computational simulation as previously discussed in [13, 22]. Furthermore, the use of the conventional linear theory causes a complete loss of information about nonlinear phenomena such as periodic, quasi-periodic and chaotic vibrations which can be predicted only by the original nonlinear equations.

In the current paper, in order to calculate the time history responses and therefore to predict the nonlinear self-excited friction-induced oscillations as well as the associated limit cycles, the nonlinear second-order differential equations of motion (i.e., Eq. (5)) are solved using the explicit Runge-Kutta time-step integration scheme. The application of this scheme requires a differential system represented in the state-space form. Namely, Eq. (5) is transformed into a first-order system as given in Eq. (10). Non-zero initial conditions corresponding to the displacements and to the velocities at time are employed to initialize the transient dynamic problem. In what follows, we focus especially on the stationary oscillations (i.e., the responses in the steady-state regime). In order to assess the frequency distribution of the self-excited vibrations of the nonlinear system, the fast Fourier transform (FFT) will be utilized.

3. Results and discussion

Two specific numerical cases will be investigated. The first one will be a classical baseline with a simple mode-coupling mechanism (i.e., the coalescence of two modes, one being stable and the other unstable). The second one deals with more complex mode-coupling mechanisms in the presence of successive appearances and disappearances of correlated stabilities and instabilities as well as the crossing phenomenon between modes.

In order to propose a minimal model able to study different coalescence patterns with simple mode-coupling phenomena and complex ones which have not been reported in the extant literature, several tests are to be performed by means of three different configurations of the new phenomenological developed model presented in this article, see Fig. 1(a). The different configurations have been chosen in order to illustrate a classical baseline with a simple mode-coupling mechanism which has been previously reported in [5, 7, 17] (i.e., the coalescence of two modes, one being stable and the other unstable) and more complex coalescence patterns with the possibility of multi-instabilities and the successive appearances and disappearances of linked stabilities and instabilities in addition to the crossing phenomenon between modes. For all these configurations, not only the stability of the static equilibrium point but also the nonlinear self-excited friction-induced oscillations will be undertaken.

The main properties of these three configurations, which include the masses and the linear damping and stiffness coefficients defined in Section 2.1, are given in Table 1. It can be noted that the configuration 1 corresponds approximately to two separated simplified Hultén systems because the coupling stiffness coefficient is small when compared to the other ones. It is thus expected that the coalescence patterns found for each block of the system and the nonlinear behaviors will be significantly similar to those observed in [5, 7]. In the case of the configuration 2, only the coupling stiffness coefficient is modified, while the other parameters are the same as used for the configuration 1, i.e., the coupling becomes much stronger. The configurations 2 and 3 are similar except for the linear stiffness coefficient of the vertical spring attached to the second block of mass . It is expected that the last two configurations give rise to more complex phenomena of coalescence patterns due to the stronger coupling between the two blocks. The three coefficients of friction used in the adopted four-degree-of-freedom model are assumed to be equal all along the numerical simulations, i.e., . The cubic nonlinear stiffness coefficients of the horizontal springs attached to the first and second blocks are 106 N/m3, see Section 2.1. This value is used as a first procedure to perform the nonlinear dynamic analysis. Then, a parametric study is presented by means of three other nonlinear stiffness coefficients ( 104 N/m3, 108 N/m3 and 1010 N/m3).

Table 1Essential characteristics for three configurations of the developed Hultén system

Configuration number | kg | N·s/m | N/m | N·s/m | N/m | kg | N·s/m | N/m | N·s/m | N/m | N·s/m | N/m |

1 | 1 | 1 | 6000 | 1 | 3000 | 1 | 1 | 3000 | 1 | 1000 | 1 | 100 |

2 | 1 | 1 | 6000 | 1 | 3000 | 1 | 1 | 3000 | 1 | 1000 | 1 | 1000 |

3 | 1 | 1 | 6000 | 1 | 3000 | 1 | 1 | 3000 | 1 | 2000 | 1 | 1000 |

3.1. Stability analysis and coalescence patterns

The first step of the dynamic analysis of a mode-coupling mechanism is to evaluate the stability of the static equilibrium points for a given set of parameters [5, 6, 13]. As explained in Section 2.2, for a system of nonlinear differential equations (see Eq. (5)), the stability is studied by considering the system linearized at the static equilibrium point and by applying the complex eigenvalue analysis. Namely, the static equilibrium point under study is stable if all the eigenvalues of the linearized system have negative real parts, while it is unstable if at least one of the eigenvalues has a positive real part, i.e., when an instability of the system occurs, the unstable equilibrium point leads to friction-induced oscillations of the proposed nonlinear mechanism.

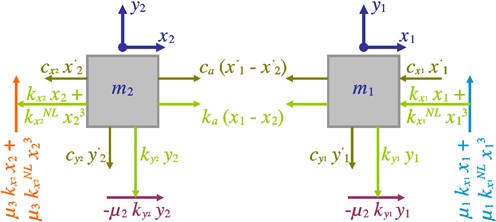

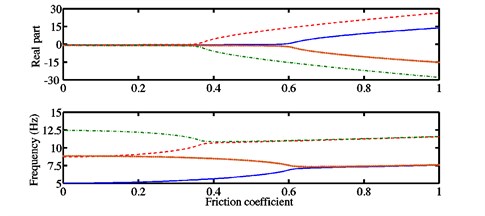

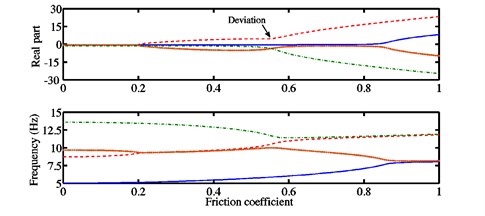

Since the developed model is based on four degrees-of-freedom, four modes exist. Figs. 2(a)-4(a) illustrate the stability charts and the evolution of the corresponding natural frequencies (obtained from the real and imaginary parts of the complex eigenvalue analysis) with respect to the friction coefficient for the chosen three configurations. The dashed, solid, dashed-dotted and dotted lines (see Figs. 2(b)-4(b)) correspond to the four modes , , and respectively. Tables 2-4 present a summary of the real parts of the eigenvalues and of the natural frequencies for the different modes of the three model configurations distinguished in Figs. 2(b)-4(b) as a function of the friction coefficient . It is shown that the number of instabilities increases for increasing values of . Moreover, the modes and are initially stable and then can become unstable, while the modes and always are stable whatever the value of the friction coefficient in the zone of interest [0; 1].

In Fig. 2(a) studying the configuration 1, there are two pairs of stable modes with different frequencies for at which the instability begins to occur. When , a new pair of unstable and stable modes (i.e., either the pair of modes and or that of modes and ) can be seen. The first Hopf bifurcation is detected at the friction coefficient and the frequency of the associated unstable mode (dashed line) is 10.03 Hz. The second Hopf bifurcation appears at the coefficient of friction and the frequency of the associated unstable mode (solid line) is equal to 6.59 Hz. After the Hopf bifurcation point (), the frequencies of the corresponding pair of stable and unstable modes are almost identical. As expected, increasing the coefficient of friction after always increases the real parts of the unstable modes (i.e., modes and dashed and solid lines) and decreases those of the stable modes (i.e., modes and dashed-dotted and dotted lines). This is because the first model configuration represents roughly two separated simplified Hultén models which highlight the most classical investigated behavior of a mode-coupling mechanism.

Fig. 2a) Stability chart and associated natural frequencies, b) real parts of the eigenvalues and frequencies for each mode in the case of the configuration 1

a)

b)

Table 2Real parts of the eigenvalues and corresponding natural frequencies as a function of the coefficient of kinetic friction μ for the first proposed model configuration

Friction coefficient | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.5 | –0.48 | –0.4 | –0.26 | 4.38 | 9.85 | 13.88 | 17.38 | 20.59 | 23.58 | 26.41 |

Frequency (Hz) | 8.72 | 8.81 | 9.07 | 9.63 | 10.67 | 10.82 | 10.95 | 11.09 | 11.24 | 11.39 | 11.55 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.5 | –0.5 | –0.49 | –0.46 | –0.42 | –0.31 | 0.62 | 5.91 | 9.03 | 11.55 | 13.75 |

Frequency (Hz) | 5.03 | 5.07 | 5.18 | 5.37 | 5.65 | 6.07 | 6.87 | 7.22 | 7.33 | 7.43 | 7.54 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –1.03 | –1.04 | –1.09 | –1.24 | –5.89 | –11.36 | –15.38 | –18.88 | –22.09 | –25.08 | –27.91 |

Frequency (Hz) | 12.43 | 12.37 | 12.17 | 11.74 | 10.87 | 10.91 | 11.02 | 11.14 | 11.28 | 11.43 | 11.59 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.97 | –0.98 | –1.03 | –1.04 | –1.08 | –1.18 | –2.11 | –7.41 | –10.53 | –13.04 | –15.25 |

Frequency (Hz) | 8.86 | 8.83 | 8.77 | 8.66 | 8.48 | 8.18 | 7.53 | 7.35 | 7.42 | 7.5 | 7.6 |

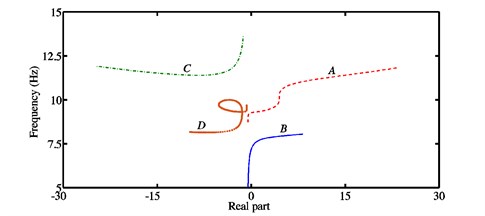

Fig. 3a) Stability chart and associated natural frequencies, b) real parts of the eigenvalues and frequencies for each mode in the case of the configuration 2

a)

b)

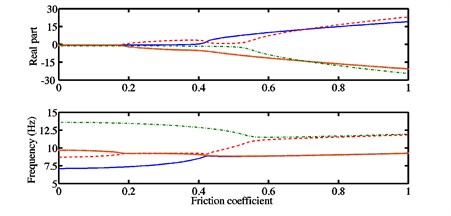

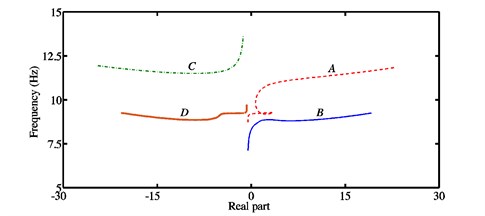

Fig. 4a) Stability chart and associated natural frequencies, b) real parts of the eigenvalues and frequencies for each mode in the case of the configuration 3

a)

b)

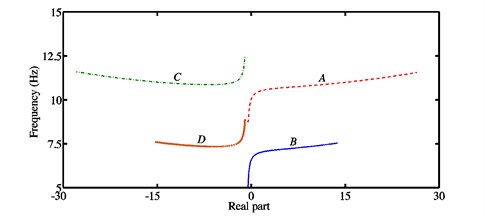

In Fig. 3(a) concerning the configuration 2, the first and second Hopf bifurcations are found at 0.205 and respectively, i.e., owing to the coupling stiffness coefficient being greater than that used in the configuration 1, the friction coefficient is shifted down for the mode , while it is shifted up for the mode . The frequencies of the associated unstable modes are 9.28 Hz and 7.21 Hz. In Fig. 4(a) corresponding to the configuration 3, the first and second Hopf bifurcations are obtained at and respectively. The frequencies of the associated unstable modes are equal to 9.2 Hz and 8.34 Hz. Unlike the case of the configuration 1, after the first Hopf bifurcation point , the real parts of one of the stable modes (i.e., mode ) in the configuration 2 can increase (before the second Hopf bifurcation point is reached) and those of one of the unstable modes (i.e., mode ) in the configuration 3 can decrease for a limited zone of interest of the friction coefficient . As can be observed in Figs. 3(a) and 4(a), when , the frequencies of the modes and begin to be coupled together. The increase of leads to their separation such that the frequencies of the modes and are coupled and that the frequencies of the modes and are almost equal for . The separation of the frequencies of the modes and in Fig. 3(a) is due to a deviation in the curve of the real parts of the mode recognized at and related to a new possible bifurcation which is questionable and will be verified through the nonlinear dynamic analysis discussed in the next section, while their separation in Fig. 4(a) is caused by the appearance of the other unstable mode (i.e., mode ).

By means of the previous observations, it is clearly shown that complex coalescence patterns with the possibility of multi-instabilities and the successive appearances and disappearances of correlated stabilities and instabilities (i.e., the coalescence or separation of the frequencies of two modes, one being stable and the other unstable) can be observed for the last two configurations due to the stronger coupling between the two blocks when compared to the first configuration.

3.2. Nonlinear self-excited oscillations

When an unstable equilibrium point appears, nonlinear transient and steady-state self-excited friction-induced oscillations can be produced. If only the linearized stability analysis of an equilibrium point is considered, it is then inconceivable to investigate the possible number of frequency components due to unstable modes found in the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations. Thus, the second step of the dynamic analysis is to predict the contribution of the harmonic components of the unstable fundamental frequencies and of their combination in the nonlinear vibrations. This step is of prime interest at the design stage in order to understand clearly the evolutions of the nonlinear behavior for a mode-coupling mechanism with instability of the equilibrium points.

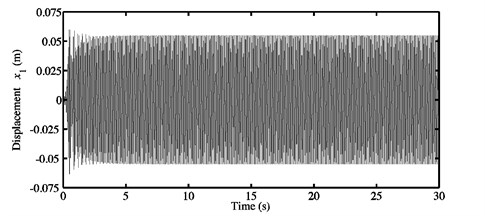

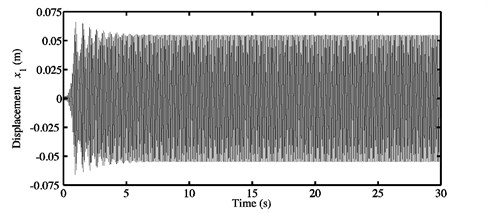

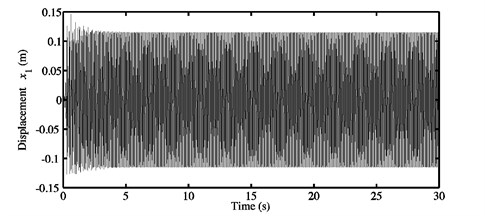

Fig. 5a) Time history response, and b) FFTs of the nonlinear stationary response computed at μ=0.5 for the first configuration

a)

b)

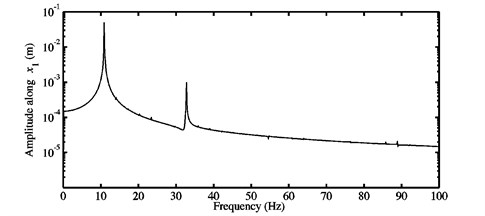

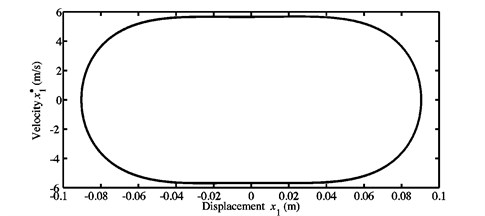

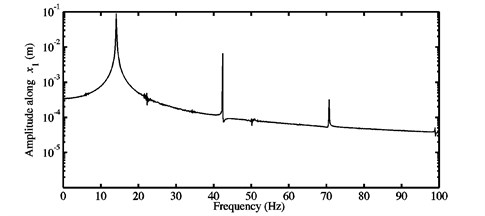

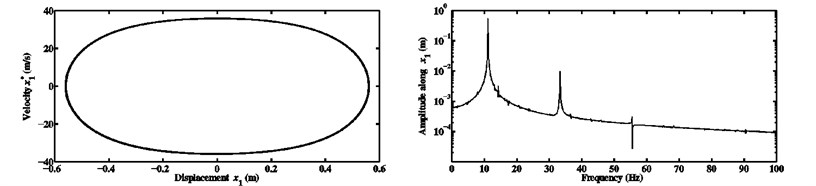

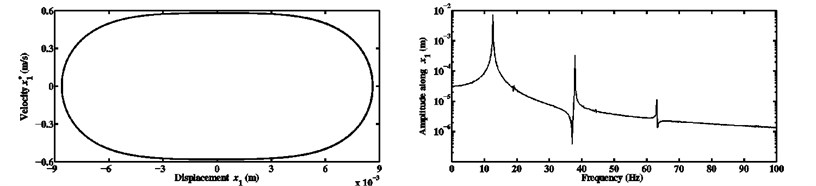

Fig. 6Limit cycles of the nonlinear self-excited vibrations of the blocks a) m1, and b) m2 obtained at μ=0.7 for the first configuration

a)

b)

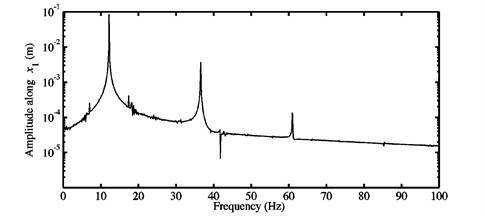

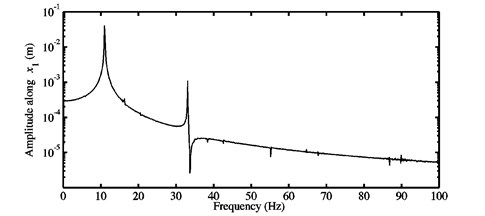

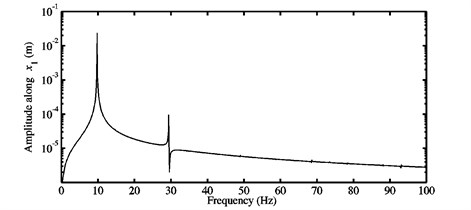

Fig. 7FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited motions of the blocks a) m1, and b) m2 obtained at μ=0.7 for the first configuration

a)

b)

In order to calculate the time history responses and to investigate the nonlinear behavior of the system under study, the Runge-Kutta integration algorithm is used. The initial conditions (i.e., the displacements and the velocities at time ) for the transient dynamic computations are set to be . The final integration time is chosen to be equal to s in order to exclude the transient effects and to predict the nonlinear self-excited vibrations when the steady-state responses are reached. On the other hand, the spectral analysis and the fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) of the nonlinear steady-state friction-induced motions are performed in order to compare the dynamic behavior obtained through the nonlinear transient numerical simulations with the complex eigenvalue analysis carried out in the previous section. Although the linearized stability analysis and the linearization about a static equilibrium point are not valid for the transient dynamic analysis, the major objective of the mentioned comparison is to verify the correlations between the linearized analysis (used for the detection of instabilities) and the transient Runge-Kutta integration scheme (employed for the description of the nonlinear dynamic behavior in the time domain). In this section, it will be proved that the nonlinear stationary vibrations can be simple or more complicated than expected.

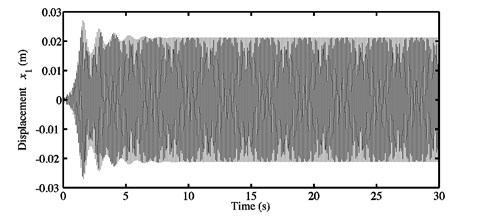

The cubic nonlinear stiffness coefficients employed in Figs. 5-13 are 106 N/m3. First of all, Fig. 5 displays the nonlinear transient and stationary responses in the time domain and the FFTs relative to the nonlinear steady-state self-excited oscillations for the configuration 1 of the adopted mechanical system and a constant coefficient of friction 0.5. The selected displacement corresponds to the degree-of-freedom of the first block in the direction. From Fig. 5(a), it can be shown that initially, the displacement magnitude grows (from zero according to the initial conditions) in an accelerated way with time and then decreases very slightly until the nonlinear steady-state periodic oscillations about the unstable equilibrium point are reached. Moreover, the stationary response plotted in Fig. 5(a) is linked with one of the simplest and most classical nonlinear dynamic behaviors investigated when a single instability phenomenon occurs. The FFTs seen in Fig. 5(b) exhibit two significant peaks and the associated frequencies included in the nonlinear stationary vibrations are listed in Table 5. The first peak, which is the biggest one, can be related to the contribution of the fundamental frequency given in Table 2. Namely, the prevalent frequency for the stationary self-excited oscillations is close to the frequency of the mode (i.e., of the first unstable mode which appears at as explained in the previous section) predicted at . The frequency at the second peak is rather equal to a multiple (i.e., a super-harmonic) of the fundamental frequency and concerns precisely the harmonic component . The presence of super-harmonics is only due to the cubic nonlinear stiffness coefficients. The results of Fig. 5 demonstrate the fact that the nonlinear stationary oscillations generated by an unstable static equilibrium point can be very simple and harmonic of period equal to the inverse of the fundamental frequency of the single unstable mode computed at the friction coefficient because only one fundamental frequency and its super-harmonics participate in the nonlinear oscillations. In other words, they give an example of classical nonlinear harmonic self-excited friction-induced vibrations of the mode-coupling mechanism with the participation of a single instability. Anyway, it can be reminded that the stability analysis of the system linearized about a static equilibrium point cannot investigate the harmonic components of the fundamental frequencies and their combination involved in the nonlinear stationary motions.

As shown in Section 3.1, the configuration 1 of the developed Hultén model under study can be subjected to two unstable modes (i.e., modes and ) when the coefficient of friction is greater than corresponding to the second Hopf bifurcation point. Thus, in order to know accurately the role of these two unstable modes in the dynamic behavior if , the nonlinear stationary self-excited friction-induced vibrations will be investigated. Fig. 6 introduces a comparison between the limit cycles of the nonlinear steady-state motions for the two blocks of the first proposed model configuration and the range of interest [25; 30 s] in the case where . The associated FFTs as well as the contribution of the harmonic components of the fundamental frequencies and/or of their combination are illustrated in Fig. 7. The type of oscillations of the first block seems to be periodic as can be seen in Fig. 6(a). Unlike the previous case, quasi-periodic oscillations of the second block are distinguishable during the steady-state regime, see Fig. 6(b). These observations are very important because they clarify the fact that the self-excited vibrations of all the discrete system components (or of all the nodes of a finite element model) have to be more and more examined carefully in order to validate wholly a mode-coupling mechanism (such as a brake system) during the design phase. Even if the quasi-periodic motions of a system component can be significantly small compared to the periodic motions of other components in the steady-state regime (see the limit cycles plotted in Fig. 6), this nonlinear dynamic behavior of a mode-coupling mechanism can be a key question for predicting dangerous and suitable operating conditions.

Fig. 8a) Time history response, and b) FFTs of the nonlinear stationary response investigated at μ=0.3 for the second configuration

a)

b)

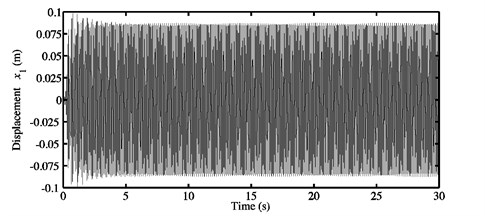

Fig. 9a) Time history response, and b) FFTs of the nonlinear stationary response investigated at μ=0.5 for the second configuration

a)

b)

Fig. 7(a) shows peaks identified in the FFTs of the nonlinear stationary vibrations of the first block , while Fig. 7(b) highlights peaks relevant to the second block . Even if the stability analysis really is not sufficient to assess the frequency components of the nonlinear self-excited oscillations of the mechanical system being studied, it is demonstrated that this analysis has previously predicted the unstable modes contained in the oscillations. It is recalled that the fundamental frequencies of the self-excited vibrations are close (but not equal) to the predicted frequencies of the unstable modes. These differences are due to the fact that the linear conditions (i.e., the stability analysis of the system linearized about an initial equilibrium point) are not valid during transient oscillations and that the value of fundamental frequencies may evolve during the transient regime. For the considered coefficient of friction 0.7, the fundamental frequencies and of both the first and second unstable modes (i.e., modes and ) are found in the FFTs of the nonlinear motions of the second block and their values are provided in Table 2. In addition to the fundamental frequencies and of the modes and , their super-harmonics and (with and positive integers) and the combination of the super-harmonics can be seen in Fig. 7(b) and are detailed in Table 5. This result confirms clearly the interaction of the two instabilities yielding the sum and the difference of frequencies . The FFTs exhibit the super-harmonics and . Moreover, they indicate the combination of the harmonic components , , , , , , , , and . However, all these combinations are less important than the fundamental frequencies as well as and than the combination . It should be noted that the presence of the combination of the frequency components is indicative of strong coupling of the two unstable modes leading to nonlinear stationary quasi-periodic self-excited vibrations of the second block . The coexistence of fundamental frequencies and , the super-harmonic components and their combination is due to the interaction between the cubic nonlinearities and the frictional interfaces. Lastly, a contribution of the frequency components , and is discovered in the FFTs of the nonlinear motions of the first block for (see Fig. 7(a)), i.e., the nonlinear oscillations are periodic as explained previously due to the presence of harmonic components being multiples of the fundamental frequency of the first unstable mode (i.e., mode ).

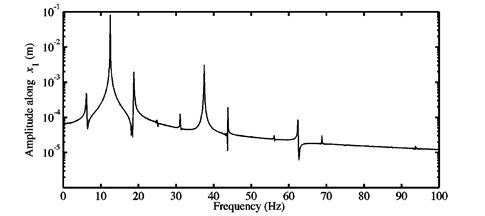

Fig. 10a) Time history response, and b) FFTs of the nonlinear stationary response investigated at μ=0.7 for the second configuration

a)

b)

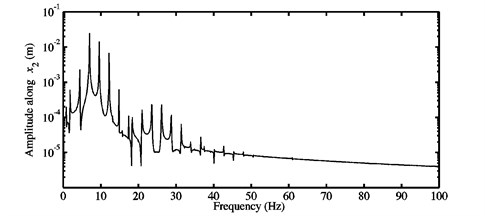

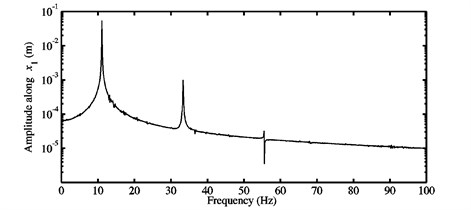

Figs. 8-11 illustrate the nonlinear transient and steady-state responses in the time domain and the FFTs relative to the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations for the configuration 2 of the investigated mechanism and various coefficients of friction ( 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9). The chosen displacement always represents the degree-of-freedom of the first block in the direction. According to Figs. 8(a)-11(a), it can be concluded that a fast increase of the transient oscillations (from zero owing to the initial conditions) is followed by a slight decrease until the nonlinear stationary periodic motions about the unstable static equilibrium point are obtained. Furthermore, the amplitudes of the stationary responses presented in Figs. 8(a)-11(a) become larger and larger when the coefficient of friction increases. Three different dynamic behaviors can be recognized in the nonlinear stationary time history responses. The first behavior (see Figs. 8(a) and 9(a)) corresponds to a simple and classical nonlinear behavior detected if only one instability phenomenon occurs. In this case, the considered friction coefficients 0.3 and 0.5 are positioned between and defining the first and second Hopf bifurcation points, see Section 3.1. The FFTs shown in Figs. 8(b) and 9(b) highlight two observable peaks. The associated frequencies contained in the nonlinear steady-state oscillations are presented in Table 6. The first peaks (which always represent the largest ones) can be linked with the contribution of the fundamental frequencies reported in Table 3 for the coefficients of friction 0.3 and 0.5. In other words, the paramount frequencies for the stationary self-excited vibrations concern the frequencies of the mode (i.e., of the first unstable mode seen at as explained in the previous section) computed at 0.3 and 0.5. The frequencies at the second peaks in Figs. 8(b) and 9(b) are quite equal to super-harmonics of the fundamental frequencies predicted at 0.3 and 0.5 and related exactly to the harmonic components . As a consequence, Figs. 8(b) and 9(b) confirm the observations pointed out in Figs. 8(a) and 9(a) and the fact that the first dynamic behavior presented above is not complex and is described by classical nonlinear self-excited friction-induced vibrations of the mode-coupling mechanism which are harmonic of period equal to the inverse of the fundamental frequencies of the first unstable mode calculated at 0.3 and 0.5. Namely, the first behavior is created through the interference of a single instability.

Fig. 11a) Time history response, and b) FFTs of the nonlinear stationary response investigated at μ=0.9 for the second configuration

a)

b)

The second behavior is illustrated in Fig. 10(a) and (b) which displays the time history response and the FFTs of the nonlinear stationary oscillations investigated at . As previously seen in Section 5.1, this case corresponds to a single instability predicted by the stability analysis just after the deviation in the curve of the real parts of the first unstable mode (i.e., mode ), see Fig. 3(a). The FFTs presented in Fig. 10(b) exhibit many considerable peaks and the associated frequencies involved in the nonlinear stationary self-excited motions are given in Table 6. The second peak concerns the fundamental frequency included in Table 3 for the coefficient of friction , while the first peak can be relevant to half (i.e., a sub-harmonic) of , i.e., . The frequencies at the other peaks are equal to super-harmonics of and more properly to , , , and .

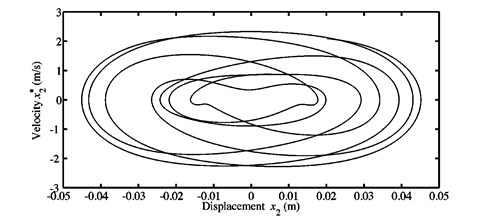

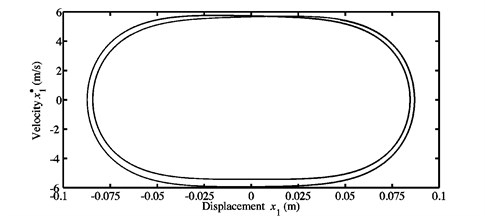

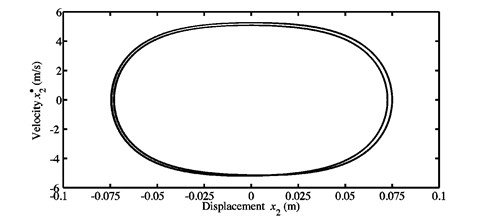

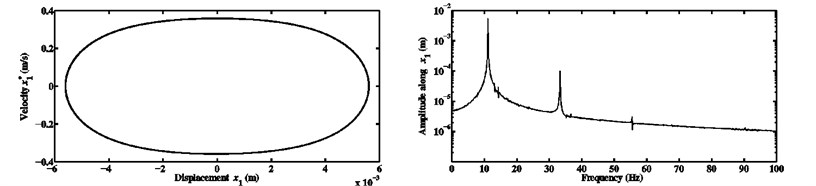

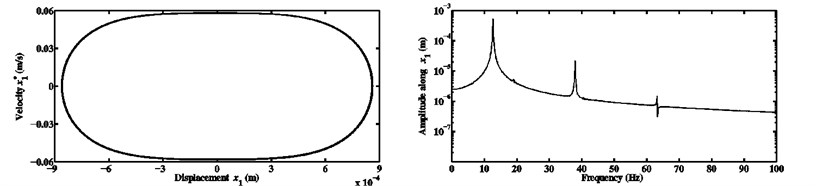

Fig. 12Limit cycles of the nonlinear self-excited vibrations of the blocks a) m1, and b) m2 obtained at μ=0.7 for the second configuration

a)

b)

Table 3Real parts of the eigenvalues and corresponding natural frequencies as a function of the coefficient of kinetic friction μ for the second proposed model configuration

Friction coefficient | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.5 | –0.5 | –0.22 | 2.56 | 3.91 | 4.5 | 7.39 | 12.67 | 16.69 | 20.17 | 23.32 |

Frequency (Hz) | 8.72 | 8.81 | 9.25 | 9.43 | 9.65 | 10.03 | 10.97 | 11.29 | 11.48 | 11.65 | 11.82 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.5 | –0.5 | –0.49 | –0.49 | –0.47 | –0.45 | –0.41 | –0.33 | –0.08 | 4.17 | 8.22 |

Frequency (Hz) | 5.03 | 5.06 | 5.14 | 5.27 | 5.46 | 5.72 | 6.04 | 6.46 | 7.08 | 7.91 | 8.05 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –1.28 | –1.29 | –1.32 | –1.39 | –1.54 | –2.04 | –8.02 | –13.88 | –18.03 | –21.56 | –24.75 |

Frequency (Hz) | 13.6 | 13.56 | 13.45 | 13.24 | 12.9 | 12.29 | 11.4 | 11.49 | 11.62 | 11.77 | 11.92 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.72 | –0.71 | –0.97 | –3.69 | –4.9 | –5.01 | –1.97 | –1.45 | –1.58 | –5.77 | –9.79 |

Frequency (Hz) | 9.68 | 9.63 | 9.33 | 9.4 | 9.57 | 9.84 | 9.81 | 9.37 | 8.85 | 8.15 | 8.17 |

The results provided in Fig. 10(b) illustrate nonlinear motions with a period equal to two times the inverse of the fundamental frequency of the first unstable mode. Thus, these results verify the second dynamic behavior highlighted previously and can be explained by the fact that the considered coefficient of friction yields nonlinear stationary oscillations (more complex than those due to 0.3 and 0.5) with a change of dynamic regime, i.e., with the appearance of a bifurcation which corresponds to a period-doubling (sub-harmonic) motion for the configuration 2 of the investigated model. Fig. 12 introduces the limit cycles of the nonlinear stationary self-excited motions for the two blocks and of the second configuration and the range of interest [25; 30 s] in the case where . The degrees-of-freedom in the and directions are chosen to be the quantities of interest. The limit cycles plotted in Fig. 12 highlight closed curves which comprise two loops. They confirm the results pointed out in Fig. 10 and verify the creation of a new bifurcation at (as explained in Section 3.1) leading to period-doubling motions of the mechanical system.

Table 4Real parts of the eigenvalues and corresponding natural frequencies as a function of the coefficient of kinetic friction μ for the third proposed model configuration

Friction coefficient | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.5 | –0.5 | 0.78 | 2.91 | 3.31 | 0.85 | 7.24 | 12.45 | 16.46 | 19.95 | 23.11 |

Frequency (Hz) | 8.72 | 8.81 | 9.22 | 9.27 | 9.25 | 10.16 | 11.16 | 11.37 | 11.53 | 11.69 | 11.84 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.5 | –0.49 | –0.47 | –0.39 | 0.41 | 6.8 | 9.93 | 12.54 | 14.9 | 17.1 | 19.17 |

Frequency (Hz) | 7.12 | 7.18 | 7.37 | 7.73 | 8.52 | 8.81 | 8.86 | 8.94 | 9.03 | 9.14 | 9.25 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –1.28 | –1.29 | –1.32 | –1.38 | –1.53 | –2.12 | –8.68 | –13.94 | –17.96 | –21.46 | –24.63 |

Frequency (Hz) | 13.6 | 13.56 | 13.45 | 13.23 | 12.88 | 12.22 | 11.5 | 11.56 | 11.68 | 11.81 | 11.95 |

Mode | |||||||||||

Real part | –0.72 | –0.72 | –1.99 | –4.14 | –5.18 | –8.52 | –11.49 | –14.05 | –16.39 | –18.59 | –20.66 |

Frequency (Hz) | 9.68 | 9.6 | 9.23 | 9.22 | 9.07 | 8.85 | 8.88 | 8.96 | 9.04 | 9.15 | 9.25 |

Table 5Frequency components observed in the FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations predicted at the coefficients of friction μ= 0.5 and 0.7 in the case of the first configuration

Friction coefficient | Frequency (Hz) | Frequency components |

0.5 | 10.9 | |

32.8 | ||

0.7 | 1.8 | |

4.4 | ||

7 | ||

9.6 | ||

12.2 | ||

14.8 | ||

17.4 | ||

18.4 | ||

21 | ||

23.6 | ||

26.9 | ||

28.8 | ||

31.4 | ||

36.6 | ||

42.7 |

The third behavior (see Fig. 11(a)) coincides with that of a mode-coupling mechanism affected by two unstable modes (i.e., modes and ). The FFTs shown in Fig. 11(b) indicate the contribution of the harmonic components of the fundamental frequency in the case of the nonlinear dynamic behavior predicted at the friction coefficient . The frequencies at the peaks of the FFTs satisfy the relationship (with a positive integer) and are detailed in Table 6. An important contribution of the harmonic components , and can be observed, i.e., the nonlinear oscillations are periodic as shown previously in Fig. 11(a) relevant to the third dynamic behavior because the frequency components are multiples of the fundamental frequency . It should be illustrated that although the interaction and the coupling between the two unstable modes (i.e., modes and ) of the adopted mechanical system are expected as already mentioned above for the third dynamic behavior studied at , the combination of the super-harmonics of the fundamental frequencies and is not present.

Table 6Frequency components observed in the FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations predicted at the coefficients of friction μ= 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9 in the case of the second configuration

Friction coefficient | Frequency (Hz) | Frequency components |

0.3 | 9.8 | |

29.3 | ||

0.5 | 11 | |

33.1 | ||

0.7 | 6.1 | |

12.5 | ||

18.8 | ||

31.1 | ||

37.5 | ||

43.8 | ||

62.4 | ||

0.9 | 14.1 | |

42.4 | ||

70.7 |

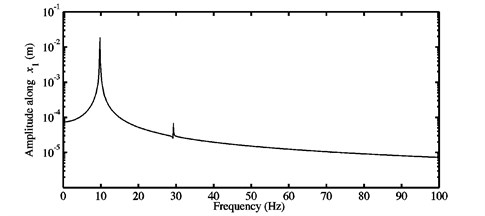

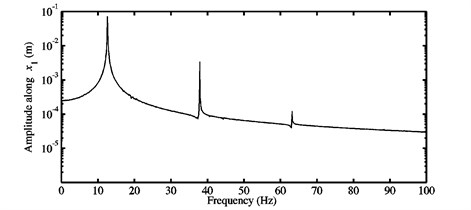

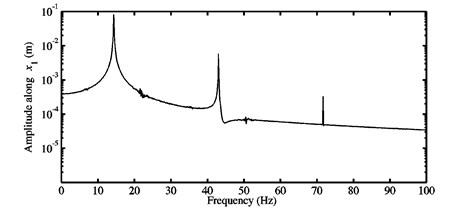

Fig. 13 achieves a comparison between the FFTs relative to the nonlinear steady-state self-excited friction-induced oscillations for the configuration 3 of the investigated mode-coupling mechanism and four coefficients of friction ( 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9). The degree-of-freedom of the first block in the direction is used as the amount of interest. The nonlinear stationary periodic vibrations about the unstable static equilibrium point can characterize two different dynamic behaviors. The first behavior (see Fig. 13(a)) emphasizes the classical nonlinear behavior discovered when only one instability phenomenon is present (as previously predicted in Section 3.1 using the stability analysis), i.e., the considered friction coefficient is situated between and corresponding to the first and second Hopf bifurcation points. The FFTs presented in Fig. 13(a) display two significant peaks and the associated frequencies involved in the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations are listed in Table 7. The first peak, which is the most important one, can demonstrate the contribution of the fundamental frequency provided in Table 4 for the coefficient of friction . Namely, the predominant frequency for the nonlinear steady-state motions represents the frequency of the mode (of the first unstable mode obtained at as shown previously) sought at . The frequency at the second peak is fairly equal to a super-harmonic of the fundamental frequency and corresponds precisely to the harmonic component . Fig. 13(a) confirms that the first nonlinear dynamic behavior stated above is classical and produced by a single unstable mode, i.e., by the participation of only one fundamental frequency and its super-harmonics in the nonlinear self-excited oscillations which are harmonic of period equal to the inverse of the fundamental frequency found at .

The second behavior (see Fig. 13(b)-(d)) highlights the FFTs of the nonlinear stationary response of the system for the coefficients of friction 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9. It is recalled that the stability analysis predicts a mode-coupling mechanism governed by two unstable modes (i.e., modes and ) since the considered coefficients of friction 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9 are greater than , see Section 3.1. Fig. 13(b)-(d) illustrates the contribution of the harmonic components of the fundamental frequencies identified in the FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited motions for the configuration 3 investigated at the coefficients of friction 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9. The relationship (with a positive integer) is verified by the frequencies at the peaks of the FFTs. These frequencies are reported in Table 7. It is observed that a considerable contribution of the harmonic components can be attained: , as well as . From these observations, it is deduced that for the second dynamic behavior presented above, the nonlinear vibrations are periodic because the frequency components are multiples of the fundamental frequency . Even if the stability analysis predicts the presence of two unstable modes, it is clearly observed that the nonlinear responses do not contain the fundamental frequency (and so the potential combination of the super-harmonics of the fundamental frequencies and ). This result illustrates the fact that the stability analysis may lead to an over-estimation of the unstable modes observed during the nonlinear computational simulation.

Fig. 13FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited oscillations of the block m1 computed at different μ: a) 0.3, b) 0.5, c) 0.7, and d) 0.9 for the third configuration

a)

b)

c)

d)

Table 7Frequency components observed in the FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations predicted at the coefficients of friction μ= 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9 in the case of the third configuration

Friction coefficient | Frequency (Hz) | Frequency components |

0.3 | 9.8 | |

29.4 | ||

0.5 | 11.1 | |

33.3 | ||

55.5 | ||

0.7 | 12.6 | |

37.9 | ||

63.2 | ||

0.9 | 14.3 | |

43 | ||

71.7 |

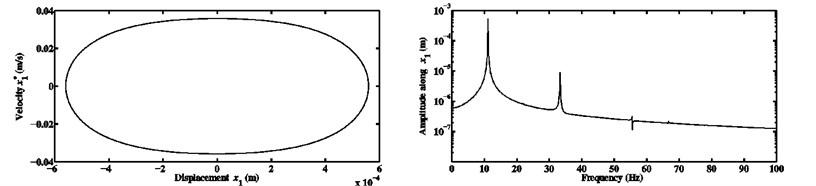

Fig. 14Limit cycles and FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited motions of the block m1 computed at μ=0.5 and kx1NL=kx2NL equal to a) 104 N/m3, b) 108 N/m3, and c) 1010 N/m3 for the third configuration

a)

b)

c)

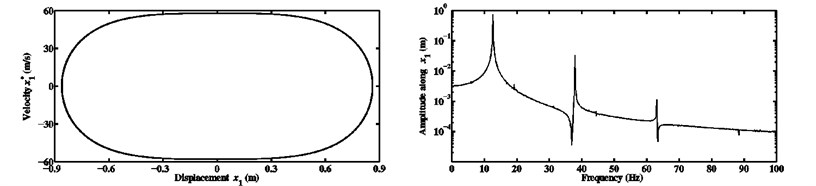

All the previous results relevant to the nonlinear dynamics have been obtained for a certain nonlinear stiffness coefficient (106 N/m3). Now, it seems interesting to study the dynamic behavior for various nonlinear cases and some explanations are to be given about the nonlinearity effects on steady-state responses in the presence of different coefficients of friction. Figs. 14 and 15 present a comparison between the limit cycles and the FFTs associated with the nonlinear stationary self-excited friction-induced vibrations for the configuration 3 of the developed Hultén model and two coefficients of friction ( 0.5 and 0.7) as well as three different values of cubic nonlinear stiffness coefficient ( 104 N/m3, 108 N/m3 and 1010 N/m3). As previously, the degree-of-freedom of the first block in the direction is considered as the quantity of interest. According to the limit cycles plotted in Figs. 14 and 15, it can be shown that the amplitudes of the nonlinear steady-state responses become smaller and smaller when the cubic nonlinear stiffness coefficients of the horizontal springs attached to the first and second blocks increase. In addition, increasing the nonlinearity does not change the type of oscillations and the latter remains periodic in our case under study. In other words, the change in the value of the cubic nonlinearity affects (as expected) only one phenomenon, i.e., the change of the amplitudes of the nonlinear self-excited oscillations. This observation has been previously discussed by Sinou and Jézéquel [7]. The FFTs seen in Figs. 14 and 15 always display three significant peaks and the corresponding frequencies involved in the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations are the same as detailed in Table 7 (corresponding to 106 N/m3). Namely, in the present study, the utilization of different nonlinearities has no influence on the contribution of the frequency components discovered in the FFTs of the nonlinear motions of the considered mode-coupling mechanism.

Fig. 15Limit cycles and FFTs of the nonlinear stationary self-excited vibrations of the block m1 computed at μ= 0.7 and kx1NL=kx2NL equal to a) 104 N/m3, b) 108 N/m3, and c) 1010 N/m3 for the third configuration

a)

b)

c)

4. Conclusions

A developed Hultén model, which is a damped minimal discrete system based on four degrees-of-freedom with frictional contact and spring cubic nonlinearities, is adopted to predict and analyze some phenomena occurring in the dynamics of a mode-coupling mechanism with frictional interfaces. Three different configurations of the proposed model are presented. The configuration 1 represents roughly two separated simplified Hultén systems because the coupling between them is relatively small. For the configurations 2 and 3, only the coupling between the two blocks and becomes stronger in order to investigate the stability and the nonlinear self-excited friction-induced vibrations for a minimal model subjected to multiple coalescence patterns.

Considering the stability analysis, it is shown that two Hopf bifurcation points and are identified. A new pair of unstable and stable modes can be noted when the friction coefficient . For the configuration 1, increasing after always increases the real parts of the unstable modes and decreases those of the stable modes. Unlike the case of the configuration 1, after , the real parts of one stable mode in the configuration 2 can increase and those of one unstable mode in the configuration 3 can decrease for a limited zone of interest of . When , the frequencies of the first stable and unstable modes begin to be coupled together. The increase of leads to their separation. In the configuration 2, this is due to a deviation in the curve of the real parts of the first unstable mode related to a new bifurcation verified by the nonlinear analysis, while in the configuration 3, this is caused by the appearance of the second unstable mode. Namely, complex coalescence patterns with the possibility of multi-instabilities and the coalescence or separation of the frequencies of two modes (one being stable and the other unstable) are observed for the last two configurations due to the stronger coupling between the two blocks when compared to the first configuration.

Considering the nonlinear transient analysis, more or less complex nonlinear behaviors of the stationary self-excited friction-induced vibrations of the system are found. It is seen that when only one unstable mode appears, the associated fundamental frequency and its super-harmonics can be involved in the nonlinear stationary periodic vibrations. If two unstable modes are predicted by the stability analysis, different nonlinear behaviors can be observed. First, the stationary vibrations can be composed not only of the fundamental frequencies and but also of the harmonic components and (with and constant positive integers) and their combination . For other configurations, it is demonstrated that although two instabilities are generated, the nonlinear stationary vibrations can be periodic and contain only the fundamental frequency of the first unstable mode and the harmonic components (with a positive integer). In this case, the second unstable mode (that is referenced with the frequency ) is not detected and the super-harmonics (with a constant positive integer) as well as the combination are not present in the nonlinear stationary responses. These results remind that the stability analysis only gives information about the initial rate of increase of instabilities and may lead to an under-estimation or an over-estimation of the unstable modes observed in the nonlinear computational simulation. The original phenomenon of period-doubling motions can be produced due to a new bifurcation corresponding to the deviation in the curve of the real parts of the first unstable mode. In this case, the nonlinear stationary self-excited oscillations are composed of the unstable fundamental frequency , its sub-harmonics and its super-harmonics.

In order to improve the current article, the comparison of the obtained theoretical prediction with experiments should be performed in the future. Moreover, a better modeling of a mode-coupling mechanism is to be required in order to predict accurately squeal events.

In conclusion, the new developed Hultén model allows to illustrate a huge variety of nonlinear behaviors for self-excited friction-induced vibrations and it may be useful as a benchmark for minimal phenomenological models subjected to multiple coalescence patterns.

References

-

Earles S. W. E., Chambers P. W. Disc brake squeal noise generation: predicting its dependency on system parameters including damping. International Journal of Vehicle Design, Vol. 8, Issues 4-6, 1987, p. 538-552.

-

Kinkaid N. M., O’Reilly O. M., Papadopoulos P. Automotive disc brake squeal. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 267, Issue 1, 2003, p. 105-166.

-

Ibrahim R. A. Friction-induced vibration, chatter, squeal, and chaos – Part II: Dynamics and modeling. Applied Mechanics Reviews, Vol. 47, Issue 7, 1994, p. 227-253.

-

Hoffmann N., Gaul L. Effects of damping on mode-coupling instability in friction induced oscillations. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, Vol. 83, Issue 8, 2003, p. 524-534.

-

Sinou J.-J., Jézéquel L. Mode coupling instability in friction-induced vibrations and its dependency on system parameters including damping. European Journal of Mechanics – A/Solids, Vol. 26, Issue 1, 2007, p. 106-122.

-

Sinou J.-J., Fritz G., Jézéquel L. The role of damping and definition of the robust damping factor for a self-exciting mechanism with constant friction. ASME Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 129, Issue 3, 2007, p. 297-306.

-

Sinou J.-J., Jézéquel L. The influence of damping on the limit cycles for a self-exciting mechanism. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 304, Issues 3-5, 2007, p. 875-893.

-

Fritz G., Sinou J.-J., Duffal J.-M., Jézéquel L. Investigation of the relationship between damping and mode-coupling patterns in case of brake squeal. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 307, Issues 3-5, 2007, p. 591-609.

-

Sinou J.-J., Jézéquel L. On the stabilizing and destabilizing effects of damping in a non-conservative pin-disc system. Acta Mechanica, Vol. 199, Issue 1, 2008, p. 43-52.

-

Chevillot F., Sinou J.-J., Mazet G.-B., Hardouin N., Jézéquel L. The destabilization paradox applied to friction-induced vibrations in an aircraft braking system. Archive of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 78, Issue 12, 2008, p. 949-963.

-

Butlin T., Woodhouse J. Friction-induced vibration: should low-order models be believed? Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 328, Issues 1-2, 2009, p. 92-108.

-

Kang J., Krousgrill C. M., Sadeghi F. Comprehensive stability analysis of disc brake vibrations including gyroscopic, negative friction slope and mode-coupling mechanisms. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 324, Issues 1-2, 2009, p. 387-407.

-

Sinou J.-J. Transient non-linear dynamic analysis of automotive disc brake squeal – on the need to consider both stability and non-linear analysis. Mechanics Research Communications, Vol. 37, Issue 1, 2010, p. 96-105.

-

Cantone F., Massi F. A numerical investigation into the squeal instability: effect of damping. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 25, Issue 5, 2011, p. 1727-1737.

-

Teoh C.-Y., Ripin Z. M., Hamid M. N. A. Analysis of friction excited vibration of drum brake squeal. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 67, 2013, p. 59-69.

-

Brunetti J., Massi F., Saulot A., Renouf M., D’Ambrogio W. System dynamic instabilities induced by sliding contact: A numerical analysis with experimental validation. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 58-59, 2015, p. 70-86.

-

Hultén J. Friction phenomena related to drum brake squeal instabilities. Proceedings of the ASME Design Engineering Technical Conferences, (Sacramento, Canada), 1997.

-

Nechak L., Berger S., Aubry E. Prediction of random self friction-induced vibrations in uncertain dry friction systems using a multi-element generalized polynomial chaos approach. ASME Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 134, Issue 4, 2012, p. 041015-1-14.

-

Nechak L., Berger S., Aubry E. Non-intrusive generalized polynomial chaos for the robust stability analysis of uncertain nonlinear dynamic friction systems. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 332, Issue 5, 2013, p. 1204-1215.

-

Sarrouy E., Dessombz O., Sinou J.-J. Stochastic study of a non-linear self-excited system with friction. European Journal of Mechanics – A/Solids, Vol. 40, 2013, p. 1-10.

-

Sinou J.-J., Thouverez F., Jézéquel L. Methods to reduce nonlinear mechanical systems for instability computation. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering: State of the Art Reviews, Vol. 11, Issue 3, 2004, p. 257-344.

-

Sinou J.-J., Loyer A., Chiello O., Mogenier G., Lorang X., Cocheteux F., Bellaj S. A global strategy based on experiments and simulations for squeal prediction on industrial railway brakes. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 332, Issue 20, 2013, p. 5068-5085.

Cited by

About this article

J.-J. Sinou acknowledges the support of the Institut Universitaire de France.