Abstract

This paper concerns with the study of wave propagation in fibre reinforced anisotropic half space under the influence of temperature and hydrostatic initial stress. Lord-Shulman theory is applied to the heat conduction equation. The resulting equations are written in the form of vector matrix differential equation by using Normal Mode technique, finally which is solved by Eigen value approach.

1. Introduction

Fibre-reinforced composite(FRC) materials are usually low weight and high strength used in construction engineering. The physical property of FRC material is governed by the theory of elasticity for different materials with the direction along the direction of fibre. Green [1] studied wave propagation in anisotropic elastic plates. Abbas and Othman [2] discussed the distribution of wave propagation under hydrostatic initial stress of fibre-reinforced materials in anisotropic half-space. Baylies and Green [3] analyse the flexural waves in fibre-reinforced laminated plates. Rogerson [4] discussed effect of penetration in a six-ply composite laminates.

Most of the thermoelasticity and generalized thermoelasticity (coupled or uncoupled) problems have been solved by potential function approach. This method is not always suitable as discussed by Dhaliwal and Sherief [5] and Sherief and Anwar [6]. These may be summarized by the initial conditions and the boundary conditions for physical problems which are directly concern with the material quantities under consideration and not with the potential function. Also, the potential function representations are not convergent always while the physical problems in natural variables constitute convergent solution. So, the alternative method of potential function approach is eigenvalue approach. In this method, we obtain a vector-matrix differential equation from the basic equations which reduces finally to an algebraic eigenvalue problem and the solutions for the field variables are obtained by determining the eigenvalues and eigenvectors from the corresponding coefficient matrix. In this theory, body forces and/or heat sources are also accommodated as in Das and Lahiri [7], Bachher et al. [8]. Now, two different models of generalized thermoelastisities are extensively used. One is Lord and Shulman (L-S) [9] theory and the other is Green and Lindsay (G-L) [10] theory. Introducing one relaxtion time parameter in L-S theory the heat conduction equation becomes hyperbolic type without violating conventional Fourier’s law. Whereas the G-L theory modified the heat conduction equation as well as the equation of motion in coupled thermoelasticitywo relaxation time parameters. There are other three models (Model I, II and III by Green and Nagdhi [11-13]) for generalized thermoelasticity concerned to the theory of with or without energy dissipation.

2. Development of governing equations

The stress-strain relation and the governing equations of motion without body forces and heat sources are written as follow:

+2(μL-μT)(aiakekj+ajakeki)+βakamekmaiaj-βij(T-T0)δij,i,j,k,m=1,2,3,

We consider the problem of a elastic half-space (x≥0) in fibre-reinforced anisotropic material with a≡(a1,a2,a3) where a21+a22+a23=1 as in I. A. Abbas [14], where the displacements are given:

We consider the direction of fibre as a≡(1,0,0) with x-axis as prefered direction, and Eqs. (1-5), reduces as given:

with:

where α11, α22 are linear thermal expansion coeeficients.

To transform the above governing equations in non-dimensional forms, we introduce the non-dimensional variables as follows:

(σ'11,σ'12,σ'22)=1ρc21(σ11,σ12,σ22),c21=A11ρ.

Using non-dimensional Eq. (13), the governing equations reduces to (eleminating primes for convenience):

where:

(ε2,ε3)=T0β11A11ρce(β11,β22),ε1=K11K22.

3. Solution procedure

3.1. Normal mode analysis: formulation of vector-matrix differential equation

For the solution of the Eqs. (14-19), physical variables can be decomposed using normal modes Eq. (20) in the following form:

where i=√-1, ω is the angular frequency and a is the wave number along x-axis.

Using Eq. (20), Eqs. (14-19) reduces to omitting ‘*’ for convenience:

where:

M53=Rp2-B1-B4B4+Rp2,M54=iaB3B4+Rp2,M62=iaε3(ω+t0ω2),

M63=ω+t0ω2+ε2a2,M64=ε22(ω+t0ω2).

Eqs. (24-26) can be written in the form of vector-matrix differential equation as [2, 8]:

where →W =[uvTu'v'T']T and A=[L11L12L21L22]. Where L11 is null matrix and L12 identity matrix of order 3×3 respectively and L21 and L22 are given by:

L21=(M41000M52M530M62M63),L22=(0M451M5400M6400).

3.2. Solution of the vector-matrix differential equation

To solve the vector-matrix differential Eq. (27), we apply the method of eigenvalue approach,

The characteristic equation of the matrix →A is given by:

The roots of the characteristic Eq. (28) are λ=λi, i= 1, 2, 3 which are of the form λ=±λ1, λ=±λ2 and λ=±λ3 and they are also eigenvalues of the matrix.

The eigenvector, →W corresponding to the eigenvalue λ can obtained as:

where δ1=a2b3-a3b2, δ2=a3b1-a1b3, δ3=a1b2-a2b1.

As in Lahiri et al. [7], the general solution of Eq. (27) which is regular as can be written as:

Hence the field variables can be written as the following:

v=A1x12e-λ1x+A2x22e-λ2x+A3x32e-λ3x,

T=A1x13e-λ1x+A2x23e-λ2x+A3x33e-λ3x.

The simplified form of Eqs. (21-23) can be written as:

where:

R12(x)=[-λ2x21+B1iax22-x23]e-λ2x,

R13(x)=[-λ3x31+B1iax32-x33]e-λ3x,

R21(x)=[-λ1B1x11+B2iax12-B3x13]e-λ1x,

R21(x)=[-λ2B1x21+B2iax22-B3x23]e-λ2x,

R21(x)=[-λ3B1x31+B2iax32-B3x33]e-λ3x,

R31(x)=[B4iax11-λ1x12]e-λ1x,

R32(x)=[B4iax21-λ2x22]e-λ2x,

R33(x)=[B4iax31-λ3x32]e-λ3x.

4. Boundary conditions

Considering the problem of a half-space ϕ, defined as follows:

In order to determine the arbitrary constants A'is, i= 1, 2, 3, we consider the boundary conditions as follows.

4.1. Case 1

a) Mechanical Boundary condition:

For stress-free surface x=0, σ11=0, σ12=0.

b) Thermal Boundary condition:

where ν is Biot’s number.

4.2. Case 2

a) Mechanical Boundary condition:

For stress-free surface x=0, σ11=-P1+P2eωt+iay, σ12=0.

b) Thermal Boundary condition:

5. Numerical analysis

5.1. Case 1

5.1.1. Distribution of different stress components

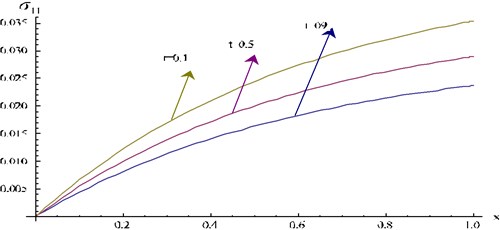

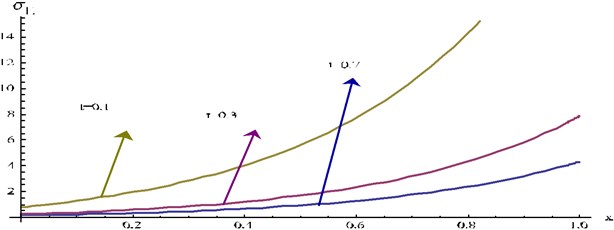

Fig. 1 represents distribution of normal stress σ11 for y=0.3.

For fixed time t, σ11 gradually increases as x increases. For fixed x numerical values of σ11 gradually decreases as t increases.

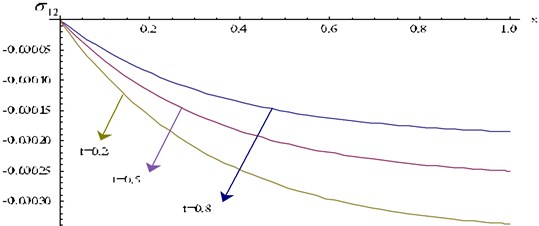

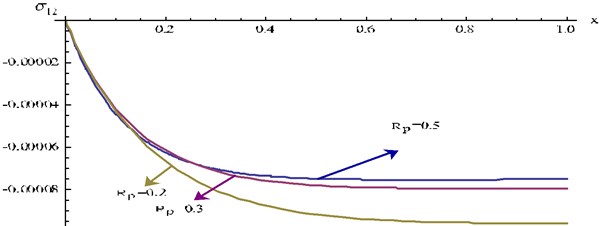

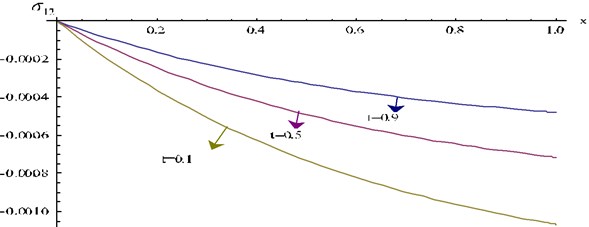

Fig. 2 represents distribution of normal stress σ12 for y=0.2.

For fixed time t, σ12 gradually decreases as x increases. For fixed x numerical values of σ12 gradually increases as t increases.

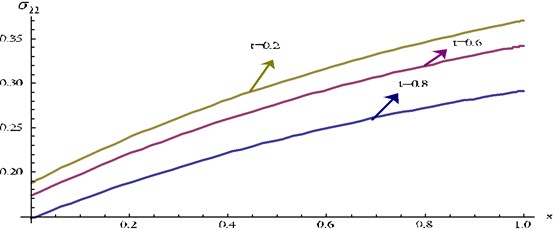

Fig. 3 represents distribution of normal stress σ22 for y=0.5.

For fixed time t, σ22 gradually decreases as x increases. For fixed x numerical values of σ12 gradually increases as t increases.

Fig. 1Stress component σ11 at y= 0.3 for different values of t verses x

Fig. 2Stress component σ12 at y= 0.2 for different values of t verses x

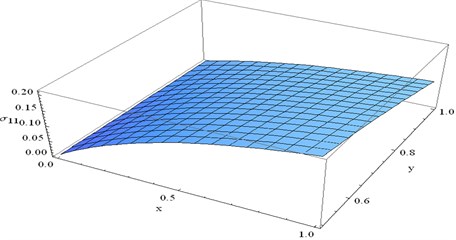

Fig. 4 represents distribution of normal stress σ11 for different values of x and y for fixed t=0.1 and ω=0.5.

x numerical value of σ11 gradually decreases as y increases. For fixed y the numerical value of σ11 gradually increases as x increases. σ11 is maximum when x=1 and y=0.

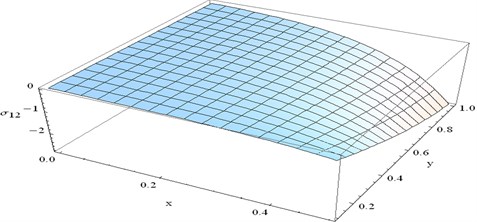

Fig. 5 represent distribution of normal stress σ12 for different values of x and y for fixed t=0.4 and ω=5.

For fixed x numerical value of σ12 gradually decreases as y increases. For fixed y the numerical value of σ12 gradually decreases as x increases. Significant changes occur in the region 0.2≤x≤0.6 and 0.6≤y≤1.0.

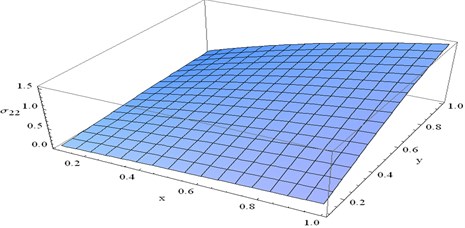

Fig. 6 represent distribution of stress component σ22 at for different values of x and y for fixed t=0.1 and 0.1.

Fig. 4Stress component σ11 at t= 0.1 and ω= 0.5 verses x and y

Fig. 5The variation of stress component σ12 at t= 0.4 and ω= 3 verses x and y

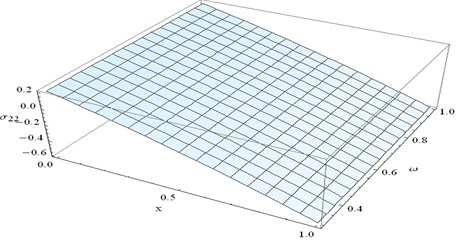

Fig. 6Stress component σ22 at t= 0.1 and ω= 0.1 verses x and y

For fixed x numerical value of σ22 gradually increases as y increases. For fixed y numerical value of σ22 gradually increases as x increases.

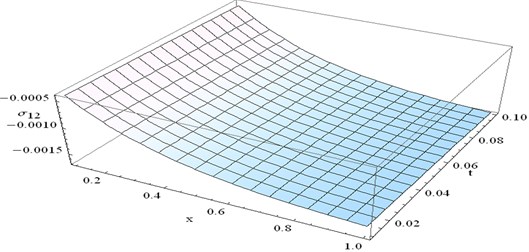

Fig. 7 represent distribution of normal stress σ12 for different values of x and t for fixed y=0.2 and 1.

For fixed x, nominal decreasing of numerical values of σ12 has been seen as t increases, while For fixed t, numerical values of σ12 decreases gradually as x increases. numerical values of σ12 minimum at x=1 and 0.02≤t≤0.1

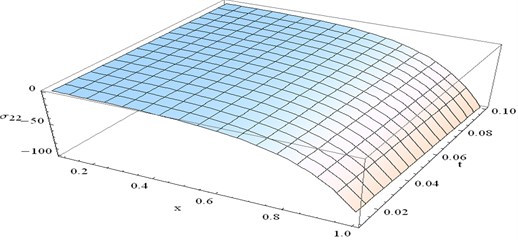

Fig. 8 represent distribution of normal stress σ22 for different values of x and t for fixed y=0.5 and 2.

For fixed x, nominal decreasing of σ22 has been seen as t increases. For fixed t, numerical values of σ12 decreases as x increases. Also, significant changes occur in the region 0.6≤x≤1.0 and 0≤t≤1.0.

Fig. 7Stress component σ12 at y= 0.2 and ω= 1 verses x and t

Fig. 8The distribution of stress component σ22 at y= 0.5 and ω= 2 verses x and t

5.1.2. Distribution of temperature

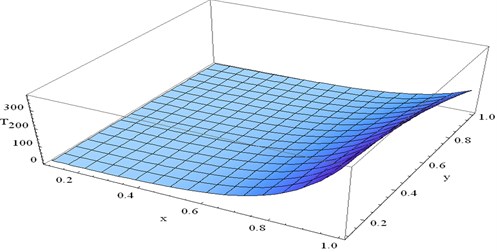

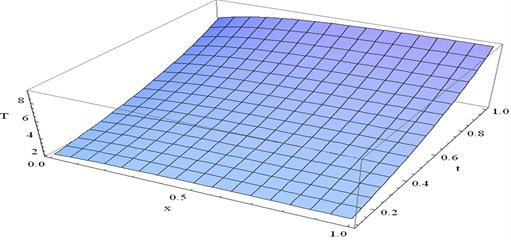

Fig. 9 represent distribution of temperature, T for different values of x and y for fixed t=0.3 and 2.

For fixed x numerical value of T gradually decreases as y increases. For fixed y numerical value of T gradually increases as x increases. T in minimum at x=0 and significant changes occurs in the region 0.6≤x≤ 1.0 and 0 ≤y≤1.0

Fig. 10 represent distribution of temperature, T for different values of x and t for fixed y=0.1 and 1.5.

Fig. 9The variation of T at t= 0.3 and ω= 2 verses x and y

For fixed t numerical value of T nominally increases as x increases. For fixed x numerical value of T gradually increases as t increases.

Fig. 11 represent distribution of temperature, T for different values of y and t for fixed x=0.5 and 3.

For fixed t numerical value of T nominally increases as y increases. For fixed x numerical values of T decreases as t increases.

Fig. 10Variation of T at y= 0.1 and ω= 1.5 verses x and t

Fig. 11Variation of T at x= 0.5 and ω= 3 verses y and t

5.2. Case 2

5.2.1. Distribution of different stress components

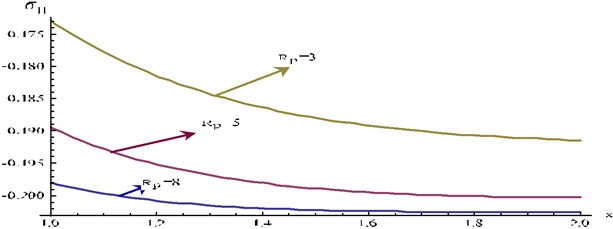

Fig. 12 represents distribution of normal stress σ11 for y=0.3, t=0.01 and 5 for different numerical values of Rp.

For fixed Rp, σ11 gradually decreases as x increases. For fixed x numerical values of σ11 gradually decreases as Rp increases.

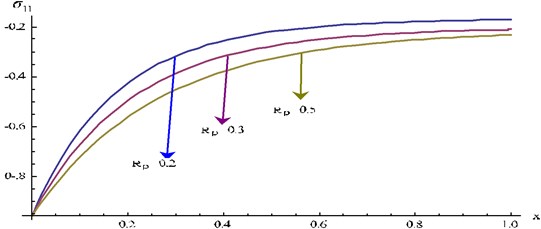

Fig. 13 represents distribution of normal stress σ11 for y=0.3, t=0.01 and 5 for different fractional values of Rp.

For fixed time Rp, σ11 gradually increases as x increases. For fixed x numerical values of σ11 gradually decreases as Rp increases. Significant changes occurred for 0≤x≤ 0.4.

Fig. 14 represents the distribution of stress component σ12 at y=0.2, t=0.03 and 0.3 for different fractional values Rp of verses x for P1=1.

For fixed time Rp, σ11 gradually decreases as x increases. For fixed x numerical values of σ11 increases as Rp increases. Significant changes occurred for 0≤x≤ 0.4.

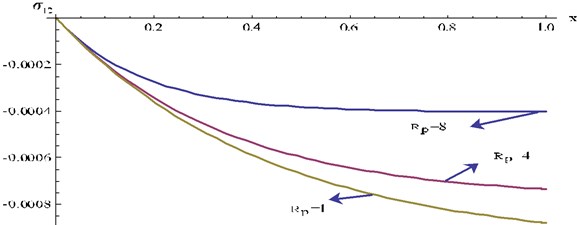

Fig. 15 represents the distribution of stress component σ12 at y=0.3, t=0.1 and 4 for different integral values Rp for P1=0.

For fixed Rp, σ12 gradually decreases as x increases. For fixed x numerical values of σ12 increases as Rp increases.

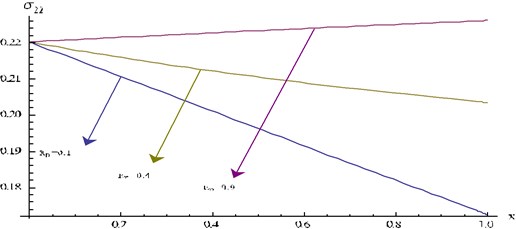

Fig. 16 represents the distribution of stress component σ22 at y=0.2, t=0.6 and 0.4 for different values Rp for P1=0.

For fixed Rp=0.9, σ22 gradually increases as x increases but for other fixed values of Rp, σ22 gradually decreases as x increases. For fixed x, σ22 gradually increases as x increases for Rp=0.9 but for other fixed values of Rp, σ22 gradually decreases as x increases.

Fig. 17 represents the distribution of stress component σ11 for different values of t for fixed y=0.2 and 1.5.

Fig. 12Stress component σ11 at y= 0.3, t= 0.01 and ω= 5 for different values Rp of verses x

Fig. 13Stress component σ11 at y= 0.2 and ω= 0.2 for different values Rp of verses x

Fig. 14Stress component σ12 at y= 0.2, t= 0.03 and ω= 0.3 for different values Rp of verses x for P1= 1

Fig. 15Stress component σ12 at y= 0.3, t= 0.1 and ω= 4 for different values Rp of verses x for P1= 0

For fixed t, the numerical value of σ11 gradually increases as x increases. For fixed x, the numerical value of σ11 gradually increases as t increases.

Fig. 18 The distribution of stress component σ12 for fixed y=0.3 and 0.5 for different values of t.

For fixed t, the numerical value of σ12 gradually decreases as x increases. For fixed x, the numerical value of σ12 gradually increases as t increases.

Fig. 16Stress component σ22 at y= 0.2, t= 0.6 and ω= 0.4 for different values Rp of verses x for P1= 0

Fig. 17Stress component σ11 at y= 0.2 and ω= 1.5 for different values of t verses x

Fig. 18Stress component σ12 at y= 0.3 and ω= 0.5 for different values of t verses x

Fig. 19Stress component σ22 at y= 0.5 and ω= 0.2 for different values of t verses x

Fig. 19 represents the distribution of stress component σ22 at fixed y=0.5 and 0.2 for different values of t.

For fixed t, the numerical value of σ12 gradually increases as x increases, but for fixed x, the numerical value of σ12 gradually decreases as t increases.

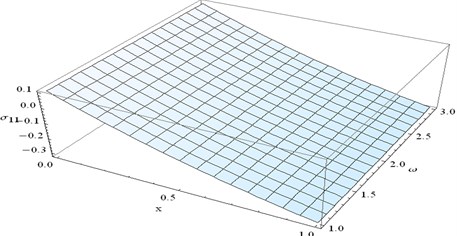

Fig. 20 represents distribution of normal stress σ11 for different values of x and for fixed t=0.3 and y=0.3.

For fixed x numerical value of σ11 remain constant as increases, but for fixed ω the numerical value of σ11 gradually decreases as x increases.

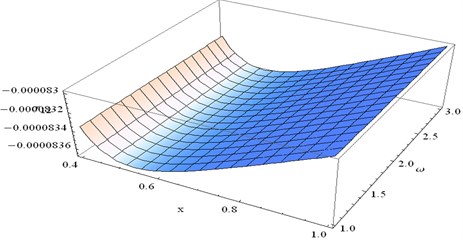

Fig. 21 represents distribution of normal stress σ12 for different values of x and for fixed y=0.3 and t=0.5.

For fixed x, nominal increasing of numerical values of σ12 has been seen as increases, while for fixed ω, numerical values of σ12 increases gradually as x increases after x=0.6 (approx.). Numerical values of σ12 minimum at x=0.5 (approx.) and 1≤t≤3.

Fig. 22 represents distribution of stress component σ22 at for different values of x and for fixed t=0.1 and y=0.4.

For fixed ω numerical value of σ22 gradually decreases as x increases. Numerical values of σ22 minimum at x=1 and 0≤ω≤1.

Fig. 20Stress component σ11 at y= 0.3 and t= 0.3 verses x and ω

Fig. 21Stress component σ12 at y= 0.3 and t= 0.5 verses x and ω

Fig. 22Stress component σ22 at y= 0.4 and t= 0.1 verses x and ω

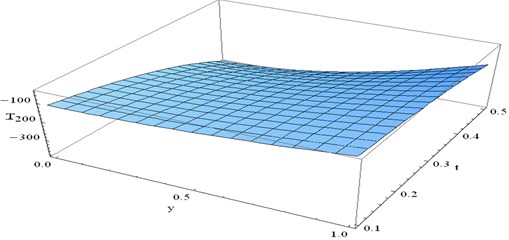

5.2.2. Distribution of temperature

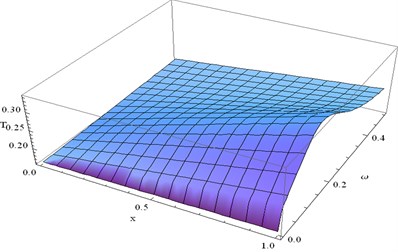

Fig. 23 represents distribution of temperature, T for different values of x and ω for fixed t= 0.1 and y= 0.4.

For fixed x numerical value of T gradually increases in the region 0≤ω≤0.3 (approx.) For fixed ω numerical value of T nominally increases as x increases.

Fig. 23The variation of T at y=0.4 and t= 0.1 verses x and ω

6. Conclusion

We consider the physical parameters in SI units given in Dhaliwal and Singh following below to obtain the numerical result to observe the effect of wave propagation:

μT=2.46×1010N/m2,μL=5.66×1010N/m2,

α=-1.28×1010N/m2,β=220.90×1010N/m2,

α11=0.017×10-4deg-1,α22=0.015×10-4deg-1,

l=0.5,T0=293K,ce=0.787×103JKg-1deg-1

K11=0.0921×1010Jm-1s-1deg-1

K22=0.0963×1010Jm-1s-1deg-1

P1=0or1,P2=0.1,P3=0.2.

References

-

Green W. A. Bending waves in strongly anisotropic plates. Quarterly Journal of Mechanics and Applied Mathematics, Vol. 35, 1982, p. 485-507.

-

Abbas I. A., Othman M. I. A. Generalized thermoelastic interaction in a fiber-reinforced anisotropic half-space under hydrostatic initial stress. Journal of Vibration Control, Vol. 18, Issue 2, 2011, p. 175-182.

-

Baylis E. R., Green W. A. Flexural waves in fiber reinforced laminated plates. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 110, 1986, p. 1-26.

-

Rogerson G. A. Penetration of impact waves in a six-ply fiber composite laminate. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 158, 1992, p. 105-120.

-

Dhaliwal R. S., Sherief H. H. Generalized thermoelasticity for anisotropic media. Quarterly of Applied Mathematics, Vol. 33, 1980, p. 1-8.

-

Sherief H. H., El-Sayed A., El-Latief A. Fractional order theory of thermoelasticity. International Journal of Solids and Structures, Vol. 47, 2010, p. 269-275.

-

Santra S., Das N. C., Kumar R., Lahir A. Three dimensional fractional order generalized thermoelastic problem under effect of rotation in a half space. Journal of Thermal Stresses, Vol. 38, 2015, p. 309-324.

-

Bachher M., Sarkar N., Lahiri A. Generalized thermoelastic infinite medium with voids subjected to a instantaneous heat sources with fractional derivative heat transfer. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 89, 2014, p. 84-91.

-

Lord H. W., Shulman Y. A generalized dynamical theory of thermoelasticity. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, Vol. 15, 1967, p. 299-309.

-

Green A. E., Lindsay K. A. Thermoelasticity. Journal of Elasticity, Vol. 2, 1972, p. 1-7.

-

Green A. E., Naghdi P. M. A re-examination of the basic results of thermomechanics. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A, Vol. 432, 1991, p. 171-194.

-

Green A. E., Naghdi P. M. On undamped heat waves in an elastic solid. Thermal Stresses, Vol. 15, 1992, p. 252-264.

-

Green A. E., Naghdi P. M. Thermoelasticity without energy dissipation. Elasticity, Vol. 31, 1993, p. 189-208.

-

Ibrahim A. Abbas Generalized magnetothermoelasticity in a fiber-reinforced anisotropic half-space. International Journal of Thermophysics, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10765-011-0957-3.