Abstract

The primary, subharmonic, and superharmonic resonances of an Euler–Bernoulli beam subjected to harmonic excitations are studied with damping and spring delayed-feedback controllers. By method of multiple scales, the non-linear governing partial differential equation is transformed into linear differential equations directly. Effects of the feedback gains and time-delays on the steady state responses are investigated. The velocity and displacement delayed-feedback controllers are employed to suppress the primary and superharmonic resonances of the forced nonlinear oscillator. The stable vibration regions of the feedback gains and time-delays are worked out based on stablility conditions of the resonances. It is found that proper selection of feedback gains and time-delays can enhance the control performance of beam’s nonlinear vibration. Position of the bifurcation point can be changed or the bifurcation can be eliminated.

1. Introduction

In the past decades, a considerable amount of research has helped us better understand the effect of time delays on the behavior of nonlinear dynamical systems, which are controlled by the linear or nonlinear feedback controllers to mitigate vibrations. The intrinsic time delays, which inevitably exist in processing of the actuation mechanisms, filters, circuits, and controllers, can lead to an unacceptable detrimental delay period between the controller input and real-time system actuation in the control engineering [1-2]. However, the time-delays feedback controllers can be utilized to change the dynamic behavior of nonlinear systems [2]. Rencently, the application of time delays in the suspension controlling has become a hot research topic.

The studies on delayed dynamic systems are basically parallel to those on the dynamic systems without any delay. The major approaches include those on stability of systems, such as eigenvalue and Lyapunov method [3], and those on the Hopf-bifurcation, the center manifold reduction [4], the Lyapunov-Schmidt [5], perturbation [6] and frequency domain [7] method. The stability criteria of linear systems, the Hopf bifurcation and chaotic behavior of non-linear systems have attracted many researchers’ attention.

The dynamic behavior of delayed systems of discrete systems has received considerable concerns. Sato et al. [8] discussed the free and forced vibration of non-linear system with time-delays, using the center current theorem and average method to study its stable periodic solution and stability. Hu et al. presented analytical and numerical studies of primary resonance and subharmonic resonance of a harmonically forced Duffing oscillator under state feedback control with a time delay [9]. Ji and Leung studied the primary, superharmonic, and subharmonic resonances of a harmonically excited non-linear s.d.o.f system with two distinct time-delays in the linear state feedback [10]. Nima and Nader [11] found that the experimental results and theoretical findings were in good agreement, which demonstrated that the non-linear modeling framework could provide a better dynamic representation of the micro cantilever than the previous linear models.

Recently, stabilization of beam with delayed feedback has raised many researchers’ interests. Mohammed et al. presented a comprehensive investigation of the effect of feedback delays on non-linear vibrations of a piezoelectric actuated cantilever beam [12]. Khaled et al. investigated the effect of time delays on stability, amplitude, and frequency-response behavior of a beam and found that even the minute amount of delays can completely alter the behavior and stability of the parametrically excited beam, leading to unexpected behavior and responses [13]. Mustapha and Mohamed [14] examined the control of self-excited vibration of a simply-supported beam subjected to axially high-frequency excitation. The primary resonance of a cantilever beam under state feedback control with a time delay was investigated [15]. Vibration control and high-amplitude response suppression could be performed with appropriate time-delays and feedback gains. Wang and Hu [16] used the Lambert W function to calculate the rightmost characteristic root of retarded time-delay systems and analyzed the stability of high order mode or the systems with multiple delays. Alhazza [17] presented a single-input and single-output multimode delayed-feedback control methodology to mitigate the free vibrations of a flexible cantilever beam. A comprehensive investigation of the effect of feedback delays on the non-linear vibrations of a piezo-electrically actuated cantilever beam is presented. Stability boundaries of mechanical controlled system with time delay was studied [18]. Qian and Tang [19] discussed the primary resonance and the subharmonic resonances of a non-linear beam under moving load by using time-delay feedback controller. Gohary et al. [20] studied the vibration suppression of a dynamical system to multi-parametric excitations via time-delay absorber.

Methods of treating weakly non-linear continuous systems can be broadly divided into three groups. In the first approach, harmonic balance method is applied to obtain a nonlinear boundary-value problem. In the second approach, the Galerkin procedure is always used to discretize the non-linear governing partial differential equation and boundary conditions. The two approximate methods are easy and straightforward for application. However, the calculation of higher-order approximate solution may be complex. In the third approach, Nayfeh et al. [21] calculated an approximate solution of the nonlinear differential equation by directly solving the continuous problem. In the study, the non-linear governing partial differential equation and boundary conditions were transformed into linear differential equations by using multiple scales directly. The obtained mode shapes were in full agreement with those obtained by using discretization because the latter was performed by using a complete set of basis functions that satisfied the boundary conditions. This method is beneficial to the elimination of coupling terms and removal of solving the multi-dimensional equations and it can easily be used to analyze the dynamic response of higher modes.

Liao et al. [22] presented a feasible methodology by which could achieve good control performance of a dynamic beam structure system with time delay effect. A spring time-delay controller was designed to achieve good control performance. In this paper, the delayed damping and spring feedback controllers are designed to change the beam’s nonlinear dynamical behavior. The feedback gains and time-delays of damping controllers are easy to set and change by using active control facilities.

In this study, the spring and damping controllers are designed to control the dynamic behavior of an inextensible Euler–Bernoulli beam in the primary, subharmonic, and superharmonic resonances. The multiple scales method is applied to obtain the linear equations, which can easily analyze the high order mode dynamic behavior of beam. The stable vibration regions of the feedback gains and time-delays are calculated by using the stability conditions of resonances. The unstable behavior of the non-linear dynamic system can be changed by the action of the spring and damping controllers. The effects of the feedback gains and time-delays on the steady state responses of the dynamic beam structure system are investigated.

2. Formulation and analysis

2.1. Primary resonance

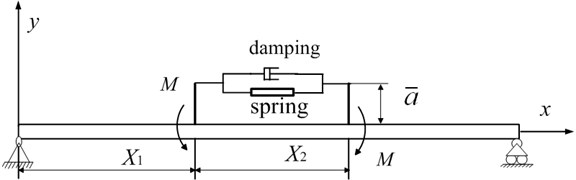

The non-linear resonance of bridge can take place under the moving load and wind, which can lead to serious accidents. The bridge is assumed to be a simply-simply supported beam and inextensible. It is also assumed to follow the Euler–Bernoulli beam theory and possess uniform cross-sectional area, where rotary inertia terms and shear deformations are negligible (see Fig. 1). The non-dimensional form of equations of motion and boundary conditions of the beam can be obtained from [23-25]:

where the primes and overdots indicate the derivatives with respect to the position and time , respectively. is the nondimensional bending vibration, the damping coefficient, the small parameter, the excitation frequency, and the perturbation parameter, H the Heaviside unit doublet function. , where is a characteristic transverse displacement, the area of cross-section, and the inertia momentum. is the length of beam., , . The active control torque is expressed as:

where , is the stiffness of the spring. , is the coefficient of the damping controller. . is the displacement of spring caused by time-delayed active controller. and are the time-delays, which are produced by the displacement time-delayed and velocity time-delayed controllers. That in Eq. (3) is corresponding to a passive structure control system.

Fig. 1Dynamic beam structure

The beam bending vibration can be expanded by order of as [22-24]:

where and are the time scales. Substituting expression (4) into the partial differential Eq. (1) and boundary conditions (2), and separating terms at orders of , one yields:

where , . The Galerkin approximation can be used to represent as a series of products of spatial functions of and time-dependent functions as:

where is the th eigenfunctions of a linear uniform beam, . is the th generalized time-dependent coordinates.

is the displacement of spring and damping caused by delayed feedback active controllers. When the functions are designed as displacement and velocity time-delayed feedback control, the simplest form with time-delays of and can be written as the linear functions of and . By introducing the time-delays, and can be expressed as:

where g is feedback gain parameter. , , and point to positive, negative and no feedback, respectively.

The solution of linear Eq. (5) is:

where is the th eigenfunction of a linear uniform beam. is the th approximate amplitude of Eq. (5), which is the function of time , is the conjugate item of . The solvability condition demands that the eigenfunctions are orthogonal, i.e.:

is the Kronecker delta. For the primary resonance, the frequency of force is close to the natural frequency of system. One can get:

where is the detuning parameter. is the circular frequency of th order mode. By substituting Eqs. (11), (12) and (13) into (7), applying the conditions of Eq. (8), and letting , the secular terms which should be equal to zero turn into:

where:

Let . Separating the real and imaginary parts of Eq. (14), we can get:

where , , . The nominal damping and detuning coefficients are expressed as the function of time-delays and feedback gains.

By setting , the steady-state response in the system can be expressed as:

From Eqs. (17) and (18), the frequency response equation of the system can be obtained by:

The peak amplitude at primary resonance, obtained from Eq. (19), can be expressed as:

For the purpose of comparison, the equation of motion for the nonlinear primary oscillator without attached controllers can be written as:

The peak amplitude at primary resonance without the controllers is written as:

As the response amplitude cannot be found analytically for a nonlinear system, a different method has to be developed here to study the performance of vibration controllers. In suppressing the primary resonance vibrations of the nonlinear oscillator, the performance of the vibration controller will be examined in the paper by defining a ratio. An attenuation ratio of nonlinear response is defined by the ratio of the amplitude of nonlinear vibrations with and without the controllers. The attenuation ratio, denoted by , can be expressed as:

The attenuation ratio of the peak amplitude of primary resonance response is also defined by the ratio of the peak amplitude of primary resonance vibrations of the nonlinear system with and without the controllers. The attenuation ratio is [25]:

As can be seen from the definition given by Eq. (24), under a fixed value of the amplitude of excitation, a small value of the attenuation ratio indicates a large reduction in the nonlinear vibrations of the nonlinear system.

For simplicity, one expresses the time-delays in the form and . The parameters become [10]:

As the phase of velocity is ahead of displacement , the phase difference can be assumed as . Eq. (25) can be expressed as:

where . The attenuation ratio , can be expressed as:

2.2. Determing of control parameters for the nonlinear vibtation system

The primary resonance response amplitude is determined by the real solution of Eq. (19). One or three real solutions can be obtained. Three real solutions exist between two points of vertical tangents (saddle-node bifurcation), which are determined by differentiation of Eq. (19) implicitly with respect to . This leads to the condition:

Its solutions are:

For the case of , three real and positive solutions of Eq. (29) exist in an interval . In the limit , this interval shrinks to the point . The critical force amplitude obtained from Eq. (19) can be written as:

For , there are three solutions. While , there is only one.

The stability of the solutions can be determined by the eigenvalues of the corresponding Jacobian matrix of Eq. (17) and (18). The corresponding eigenvalues are the roots of [10]:

As can be seen from Eq. (31), the sum of the two eigenvalues is . , which means that at least one of the eigenvalues will always have a positive real part. The system will be unstable. , there is a pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues for the system. The system is also unstable and a Hopf bifurcation may occur. If , the sum of two eigenvalues is always negative, at least one of the two eigenvalues will always have a negative real part. The other eigenvalues is zero when:

From Eq. (26), we can find that is the function of the feedback gains, damping parameters and time-delays. As a larger positive value, is prone to have the negative real parts of characteristic roots, should have a larger value in order to improve the control performance by selecting proper coefficients of damping coefficient , arm of force and the coordinates of installation of the controller.

Based on the analyses mentioned above, the sufficient conditions to guarantee the system stability are:

If there is no real solution to the Eq. (32), the sufficient conditions to guarantee the system stability are:

Letting , we can find that the inequalities satisfy the Eq. (34) and get:

If there are two real solutions to the Eq. (32), the solutions are the same as Eq. (29). Let:

We can find that . The sufficient conditions of guaranteeing the system stability can be written as:

For the fixed time-delay, the range of the feedback gains can be obtained based on the stable conditions of the primary response resonances. For the given feedback gains of the controllers, the time delay can be designed for the requirement of the suppression of the nonlinear systems.

2.3. Subharmonic resonance

In the case of subharmonic resonance, the excitation is:

Substituting Eqs. (4) and (38) into Eq. (1) and equating coefficients of like powers of , we have:

The solution to Eq. (39) can be written as:

where ,. are the conjugate items of the solution. Substituting (43) into Eq. (41), we can obtain the equation of secular terms:

Let , After substituting them into Eq. (44) and separating the real and imaginary parts, we have:

where In the case of , the steady state response corresponds to the solutions of:

By eliminating from Eqs. (47) and (48), the frequency response equation is obtained as:

There are two possibilities: either a trivial solution , or non-trivial solutions, which can be acquired by:

Solving Eq. (50), we can get:

where , . Because , the condition of the positive solution is and . The necessary condition of 1/3 subharmonic resonance can be written as:

The steady-state solutions of subharmonic resonance response are determined by the eigenvalues of the characteristic equation, which are the roots of:

2.4. Superharmonic resonance

For the case of superharmonic resonance, the solution of Eq. (39) is:

By substituting Eq. (54) into Eq. (41), the equation of secular terms is written as:

Let , . Substituting them into Eq. (55) and separating the real and imaginary parts, we have:

In the case of , the fixed points of this system are expressed as:

Eliminating from Eqs. (58) and (59), we obtain the frequency response equation:

The peak amplitude of the superharmonic resonance, obtained from Eq. (60), is given by:

For the purpose of comparison, the peak amplitude of the superharmonic resonance without control can be written as:

The attenuation ratio of the peak amplitude of superharmonic resonance response is defined by the ratio of the peak amplitude of superharmonic resonance vibrations of the nonlinear system with and without the controllers. The attenuation ratio is [26]:

The characteristic equation of superharmonic resonance response is:

The sufficient conditions of guaranteeing the system stability are:

If there is no real solution for the Eq. (65), the sufficient conditions of guaranteeing the system stability are:

Let . We can find that the inequalities satisfy the Eq. (66). We can get:

where .

If there are two real solutions for the , the solutions can be written as:

Let:

We can find that . The sufficient conditions of guaranteeing the system stability can be written as:

For the fixed time-delay, the range of the feedback gains can be obtained based on stable conditions of the superharmonic response resonances. For the given feedback gains of the controllers, the time delay can be designed for the requirement of the suppression of the nonlinear systems.

3. Case study

This section illustrates the effect of the feedback gains and time-delays on the non-linear dynamical behavior of the controlled system. The variation of attenuation ratio with time-delays and feedback gains is also discussed. The results are shown in a set of figures.

3.1. The response analysis of first mode

3.1.1. The primary resonance of first mode

The beam’s non-dimensional geometrical parameters , , and are 1, 0.05, 0.2, and 0.4, respectively. 0.2, 0.25. The coefficient of elasticity of the spring is 80. The feedback gain of the spring is 5. The coefficient of damping controllers is 0.3.

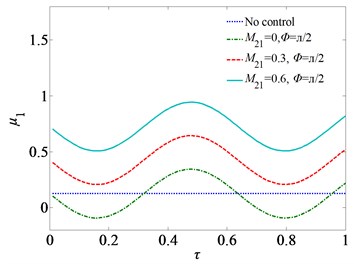

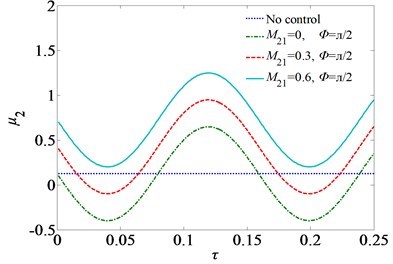

Figs. 2 and 3 show the variation of and with the time-delay for and 0, 0.3 and 0.6, respectively. We can find that varies with value of time-delays and . As larger is prone to have the negative real parts of characteristic roots, should have a larger value in order to improve the control performance. Fig. 2 shows that the value of of first order mode is larger than in the range 0.32 < τ < 0.63, which means that the attenuation ratio is smaller than 1. Fig. 3 shows that the value of of second order mode is larger than in the range . From Figs. 2 and 3, we also find that the value of time-delay for large of lower mode is larger than the higher one. For the fixed feedback gains and , different control purposes can be easily achieved by the right choice of the time-delays. should have a larger value in order to improve the suppression control performance.

Fig. 2Variation of μ1 with the time-delays of the first mode

Fig. 3Variation of μ2 with the time-delays of the second mode

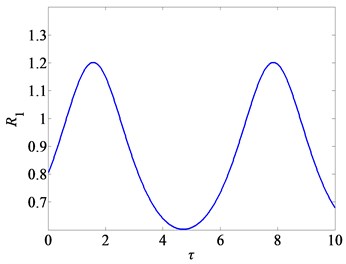

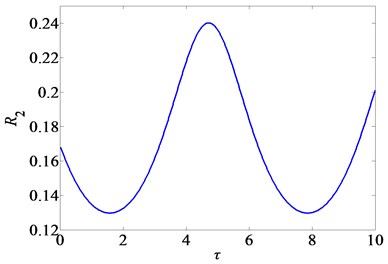

Figs. 4 and 5 show the variation of attenuation ratio with time-delays and feedback gains. As can be seen from the figures, under a fixed value of the amplitude of excitation, a small value of the attenuation ratio indicates a large reduction in the nonlinear vibrations of the nonlinear primary system. A selected value of time-delay can get a large positive value of and small attenuation ratio . From Eq. (35), we can find appropriate value of feedback controllers, which can satisfy the stability conditions. The proper selection of the feedback gains and the time-delays can guarantee the stability of the non-linear system. For the fixed feedback gains and , the good suppression control for the nonlinear vibration of beams can obtain from the right choice of the time-delays easily.

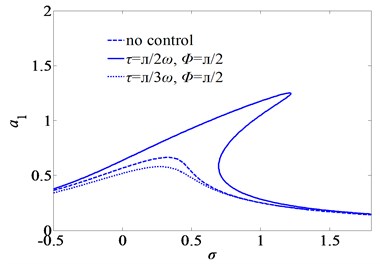

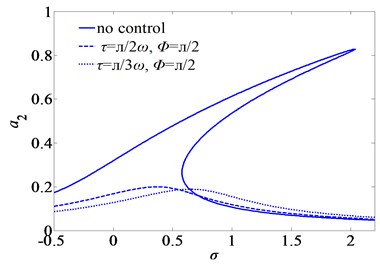

Fig. 6 shows the primary response curves of first mode for three different sets of the time-delays. There is no jump and hysteresis phenomenon when , and no control. This suggests that saddle node bifurcation and jump phenomenon can be eliminated by certain values of the time-delays. Three solutions exist in a region of coexistence of , . The bending of the frequency response curves is responsible for a jump phenomenon. Moreover, the peak amplitude of the primary resonance response at , is smaller than that in the other two cases.

Fig. 4Variation of attenuation ratio R1 with the time-delays

Fig. 5Variation of attenuation ratio R2 with the time-delays

Fig. 6First mode frequency-response curves of primary resonance for three sets of the time-delays

3.1.2. Subharmonic resonance

The excitation amplitude of the subharmonic resonance is 0.30. The curve of the subharmonic resonance with time-delays is shown as Fig. 7.

Fig. 7First mode frequency-response curves of subharmonic resonance for three sets of the time-delays

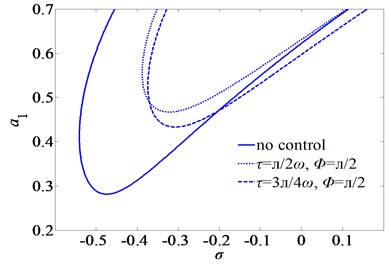

Fig. 7 shows the regions where subharmonic response exists for three different sets of time-delays. The time-delays can change the range of the occurrence of subharmonic resonance. It is noted that the regions for the existence of subharmonic responses are different. This shows that there always exist certain regions of the time-delays where subharmonic response does not exist.

3.1.3. Superharmonic resonance

The excitation amplitude of the superharmonic resonance of beam is 0.38. The curve of the superharmonic resonance with time-delays is shown in Fig. 8. For the superharmonic resonance response, the suitable choice of the time-delays and feedback gains can also improve the control performance. Moreover, the occurrence of saddle-node bifurcation, jump and hysteresis phenomena can be delayed or eliminated.

Fig. 8 shows the first mode frequency-response curves of superharmonic resonance response for three sets of the time-delays. , and 0 mean that the system is stable. When , and no control, jumps exist. This suggests that saddle node bifurcation and jump phenomenon can be eliminated by certain values of the time-delays. Thus, the control performance can be enhanced by the optimal selection of the feedback gains and time-delays.

Fig. 8Frequency-response curves of superharmonic resonance for three sets of the time-delays

3.2. Second mode response analysis

3.2.1. Primary resonance of second mode

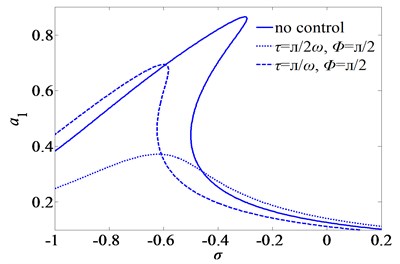

The beam’s geometry non-dimensional parameters , , and are 1, 0.05, 0.2, and 0.4, respectively. 0.2. The coefficient of elasticity is 80; the damping ratio is 0.3; the feedback gain is 10. The parameters and are 0.25, 4. The curves of the primary resonance with time-delays are shown in Figs. 9-10.

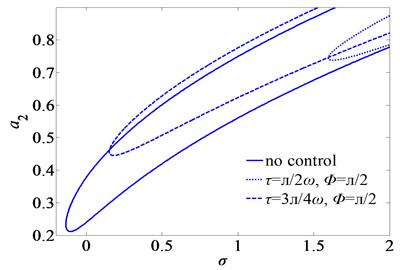

Fig. 9Second mode frequency-response curves of primary resonance for three sets of the time-delays

Fig. 9 shows the second mode frequency-response curves of primary response for three sets of the time-delays. , and , mean that the system is stable while jumps occur in the frequency response without control. This indicates that saddle-node bifurcation and jump phenomenon can be eliminated by selecting suitable time-delays.

3.2.2. Subharmonic resonance

The excitation amplitude of the subharmonic resonance of beam is 0.10. The curve of the subharmonic resonance with respect to time-delays is shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10 shows the regions where subharmonic response exists for the three different sets of time-delays. The time-delays can change the range of the occurrence of subharmonic resonance. It is noted that the regions for the existence of subharmonic responses are different. This shows that there always exist certain ranges of the time-delays where subharmonic response does not exist.

Fig. 10Second mode frequency-response curves of subharmonic resonance for three sets of the time-delays

4. Conclusions

The primary, subharmonic, and superharmonic resonances of the first and second modes of the Bernoulli-Euler beam are studied with spring and damping delayed feedback controllers. The results show that the proper selection of the feedback gains and time-delays can enhance the control performance, but the inappropriate feedback gains and time-delays may lead to instability of the system. By using the joint function of spring and damping delayed feedback control strategy, the bifurcation can be eliminated or the bifurcation point’s position can be changed.

Time-delays feedback controllers can be utilized to suppress the dynamic behaviors of nonlinear systems. Most of the vibrational energy of the nonlinear oscillator is transferred to the controllers through coupling spring and damping. The vibration controllers can effectively suppress the amplitude of oscillations of the nonlinear oscillator. Hence, by properly choosing the feedback gains and time-delays of the linked spring and damping controllers, the primary and superharmonic resonance response of the nonlinear oscillator can be reduced to relatively small amplitude. The control performance of beam’s nonlinear vibration can be improved with these delayed controllers by selecting appropriate time delays and feedback gains.

References

-

Hu H. Y., Wang Z. H. Review on non-linear dynamic systems involving time delays. Advanced Mechanics, Vol. 29, 1999, p. 501-509, (in Chinese).

-

Xu J., Pei L. J. Advances in dynamics for delayed system. Advanced Mechanics, Vol. 36, 2006, p. 17-30, (in Chinese).

-

Sun Y. J., Hsieh J. G., Yang H. C. On the stability of uncertain systems with multiple time-varying delays. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, Vol. 42, Issue 1, 1997, p. 101-105.

-

Compell S. A., Bėlair J., Ocira T., Milton J. Complex dynamics and multistability in a damped harmonic oscillator with delayed negative feedback. Chaos, Vol. 5, Issue, 4, 1995, p. 640-645.

-

Stech H. W. Hopf bifurcation calculation for functional differential equations. Journal of Math. Analysis and Applications, Vol. 109, 1985, p. 472-491.

-

Moiola J. L., Chen G. R. Hopf bifurcation in time-delayed nonlinear feedback control systems. Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Decision and Control, Vol. 1, 1995, p. 946-948.

-

Linkens D. A., Kitney R. I. Mode analysis of physiological oscillator intercoupled via pure time delays. Bulletin of Mathematics and Biology, Vol. 44, 1982, p. 57-74.

-

Sato K., Sumio Y., Okimura T. Dynamic motion of a non-linear mechanical system with time delay: Analysis of the self-excited vibration by an averaging method. Transactions of Japanese Society of Mechanical Engineering, Series C, Vol. 61, Issue 685, 1995, p. 1861-1866.

-

Hu H. Y., Dowell E. H., Virgin L. N. Resonance of a harmonically forced Duffing oscillators with time delay state feedback. Nonlinear Dynamics, Vol. 15, 1998, p. 311-327.

-

Ji J. C., Leung A. Y. T. Responses of a non-linear sdof system with two time-delays in linear feedback control. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 253, 2002, p. 985-1000.

-

Nima Mahmoodi S., Jalili N. Non-linear vibrations and frequency response analysis of piezoelectrically driven microcantilevers. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, Vol. 42, 2007, p. 577-587.

-

Daqaq M. F., Alhazza K. A., Arafat H. N. Non-linear vibrations of cantilever beams with feedback delays. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, Vol. 43, 2008, p. 962-978.

-

Alhazza K. A., Daqaq M. F., Nayfeh A. H., Inman D. J. Non-linear vibrations of parametrically excited cantilever beams subjected to non-linear delayed-feedback control. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, Vol. 43, 2008, p. 801-812.

-

Hamdi M., Belhaq M. Self-excited vibration control for axially fast excited beam by a time delay state feedback. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals, Vol. 41, 2009, p. 521-532.

-

Maccari A. Vibration control for the primary resonance of a cantilever beam by a time delay state feedback. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 259, Issue 2, 2003, p. 241-251.

-

Wang Z. H., Hu H. Y. Calculation of the rightmost characteristic root of retarded time-delay systems via Lambert W function. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 318, 2008, p. 757-767.

-

Alhazza K. A., Nayfeh A. H., Daqaq M. F. On utilizing delayed feedback for active-multimode vibration control of cantilever beams. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 319, 2009, p. 735-752.

-

Prashanth Ramachandran, Ram Y. M. Stability boundaries of mechanical controlled system with time delay. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 27, 2012, p. 523-533.

-

Qian C. Z., Tang J. S. A time delay control for a non-linear dynamic beam under moving load. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 309, 2008, p. 1-8.

-

Gohary H. A., Ganaini W. A. A. Vibration suppression of a dynamical system to multi-parametric excitations via time-delay absorber. Applied Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 36, 2012, p. 35-45.

-

Nayfeh A. H., Nayfeh S. A. On nonlinear modes of continuous systems. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 116, 1994, p. 129-136.

-

Liao J. J., Wang A. P., Ho C. M., Hwang Y. D. A robust control of a dynamic beam structure with time delay effect. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 252, Issue 5, 2002, p. 835-847.

-

Nageswara Rao B. Large amplitude free vibrations of simply supported uniform beams with immovable ends. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 155, 1992, p. 523-527.

-

Nayfeh A. H., Chin C., Nayfeh S. A. Nonlinear normal modes of a cantilever beam. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 117, 1995, p. 477-481.

-

Ji J. C., Zhang N. Suppression of the primary resonance vibrations of a forced nonlinear system using a dynamic vibration absorber. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 329, 2010, p. 2044-2056.

-

Ji J. C., Zhang N. Suppression of superharmonic resonance response using a linear vibration absorber. Mechanics Research Communications, Vol. 38, 2011, p. 411-416.

About this article

This research is supported by the Program for “Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University”, “Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions” and “Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China”.