Abstract

This article presents a robotic arm designed for mushroom picking in a greenhouse environment, taking into consideration the specific characteristics of Agaricus bisporus. The robotic arm was equipped with self-lifting and self-stretching functions, allowing it to move effectively within the restricted space of the greenhouse, while picking and placing Agaricus bisporus without causing any damage. The mechanical arm and flexible gripper were designed according to the growth environment and size of Agaricus bisporus. A finite element analysis was carried out on the flexible gripper, with the use of ABAQUS to construct a simulation model. The Yeoh model and the Mooney-Rivlin model are used as the research models, and tetrahedral linear elements C3D4H were used for meshing. By changing the positive and negative pressure of the gas inside the flexible gripper's airbag to simulate gripping and releasing actions, it was demonstrated that the deformation of the flexible gripper meets the requirements for picking actions under both the Yeoh model and the Mooney-Rivlin model. It was shown that a shear force greater than 3.2N is needed for the gripping and twisting of Agaricus bisporus within the flexible gripper to successfully complete the picking action. Finally, the experimental verification was carried out, proving the stability and feasibility of the mushroom picking robotic arm. And the design of flexible gripper control system, through the distributed computing and I/O structure, CANopen communication protocol, etc. makes the flexible gripper can perform accurate gripping tasks in complex environments, with high efficiency, reliable, flexible control performance, adaptable, and easy to expand and optimize.

Highlights

- The robotic arm has self-lifting and self-extension functions, which can move flexibly in the limited space of the greenhouse, adapt to the growth environment of Agaricus bisporus, ensure that the mushrooms are not damaged during picking and placing, and improve the picking efficiency and safety.

- The flexible fixture was simulated by ABAQUS finite element analysis using Yeoh and Mooney-Rivlin models, which verified that its deformation during the grasping and releasing of Agaricus bisporus met the requirements. The study determined the shear force threshold (>3.2N) required for picking.

- The flexible manipulator control system adopts distributed computing and I/O structure, combined with CANopen communication protocol, to realize accurate gripping in complex environment. The system is highly efficient and reliable, flexible in control, adaptable, easy to expand and optimize.

1. Introduction

Agaricus bisporus can use forestry waste materials and untreated animal manure from farms as conducive growing substrates [1-4]. By using these resources as the main ingredients, it provides carbon and nitrogen for its growth. This not only addresses local pollution concerns but also offers geographical advantages to farmers, realizing the utilization of forestry waste, saving costs, and improving economic and social benefits. With the advancement of Agaricus bisporus cultivation technology, greenhouse production of Agaricus bisporus has been successfully implemented in China [5-7]. However, large-scale production of mushrooms requires a large investment of labor. To address this issue, the integration of mechanization and automation emerges as a pivotal solution to increase mushroom yields, reduce labor requirements, enhance production efficiency, and increase farmers’ income [8-10].

Currently, most vegetable and fruit picking robots are designed for specific varieties. Engineers T. A. Pool from Greece and R. C. Harrell from Florida, USA, collaborated on developing end effector for picking citrus fruits in 1990 [11]. Boaz Arad and Jos Balendonck created a pepper picking robot that can automatically recognize, locate, and pick peppers in greenhouse environments [12]. Japanese scholar Naoshi Kondo developed a tomato picking robot capable of picking a cluster of tomatoes on a stem [13]. Shigehiko Hayashi and scholars from the Japan Agricultural Machinery Research Institute jointly developed a greenhouse nighttime strawberry picking robot, designed primarily for strawberry plants grown in elevated substrate [14]. Jedrzejowicz Piotr and Wierzbowska Izabela proposed a new type of mushroom picking framework (MPF) and provided solutions for flexible workshop scheduling problems [15]. Chuan-Pin Lu, Jun-Jian Liaw and their team applied deep learning to develop a mushroom growth measurement system based on image recognition [16].

In China, Professor Ji Changying from Nanjing Agricultural University, in collaboration with Gu Baoxing and others researchers, has developed an intelligent mobile fruit-picking robot, which enables automatic fruit picking [17]. Northeast Forestry University has developed a robot for collecting berries on a large scale, effectively alleviate labor shortages [18]. At Jilin University, Zhou Silu has researched on the structural optimization and machine vision aspects of cucumber harvesting manipulators [19]. Zhang Jianfeng et al. have proposed an adaptive robust tracking control algorithm for picking robots, ensuring stability in tracking control despite uncertainties and disturbances in outdoor farmlands [20]. Researchers at Henan University of Science and Technology, including Li Zhao and Zhang Yaoyi, have designed a strawberry picking robot [21]. Professor Zhang Tiezhong from China Agricultural University invented an eggplant picking robot [22]. Zhou Yunshan et al. have proposed the integration of computer vision technology into mushroom picking machines, enabling the mechanical arm to grasp mushrooms based on coordinate information obtained from image processing [23]. Zhou Yingying et al. have studied path planning and autonomous navigation technology for picking robots, improving the efficiency of path planning in unfamiliar environments [24]. Qiu Jianxin proposed a detection algorithm for mushroom picking robots to detect picking targets [25].

Research on agricultural and forestry picking robots has led to significant scientific achievements. Nevertheless, current automated robots for tasks such as vegetable picking and berry picking are not suitable for the picking of Agaricus bisporus. The picking of mature mushrooms is a critical step in the production process of Agaricus bisporus. In the greenhouse, mushroom cultivation beds are typically arranged in multiple parallel layers, with narrow spaces between the upper and lower layers, as well as aisles. Additionally, Agaricus bisporus are prone to damage during picking. To ensure the efficiency and quality of picking Agaricus bisporus, this paper proposes the design of a flexible mushroom picking robotic arm specialized in Agaricus bisporus picking. The robotic arm features autonomous lifting and stretching capabilities, allowing it to move within the confined spaces of the greenhouse, and pick and place Agaricus bisporus without causing damage.

2. The structure of the flexible mushroom picking robotic arm

2.1. Work environment

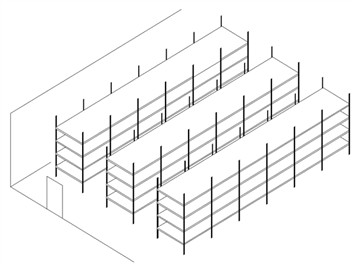

The design of this study is based on the greenhouse used for mushroom cultivation in Shenxian County, Shandong Province. The cultivation beds are arranged in multiple layers, as shown in Fig. 1. A standard mushroom greenhouse consists of three mushroom cultivation racks and four aisles, with support frames made of 80×40 mm steel bars on both sides. The height of the space between the upper and lower layers is 600 mm, and four layers are evenly distributed from bottom to top. Rectangular shapes are defined within the cross-sectional area of the steel bars, which forms a two-dimensional plane measuring 1200×1000 mm. Each rectangle represents a picking unit, and each picking unit is independent of others. There are 18 basic picking units in each layer.

2.2. Mechanical structure and technical parameters

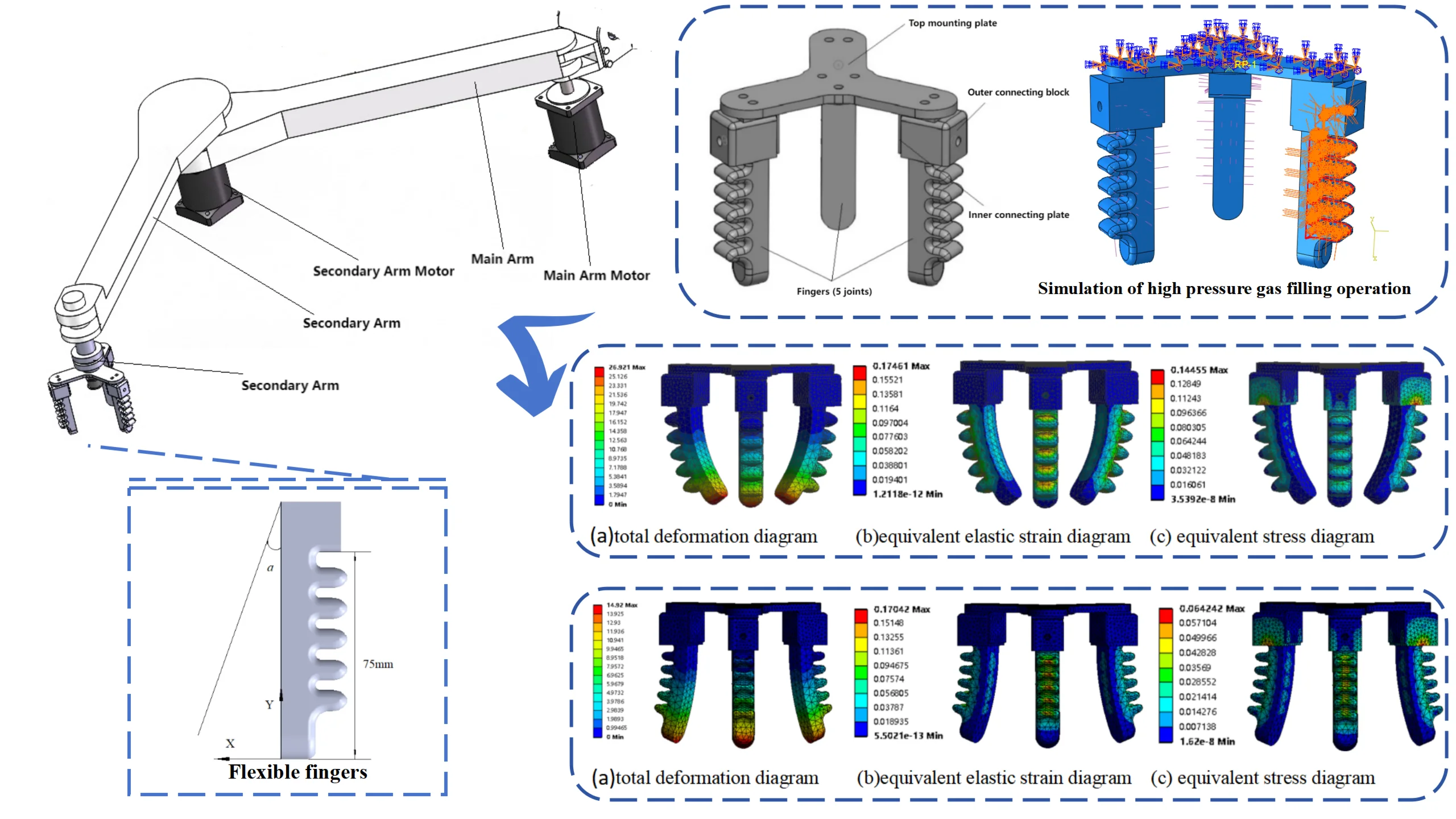

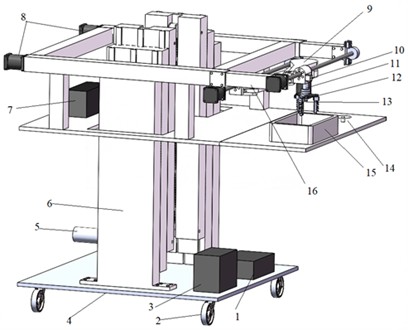

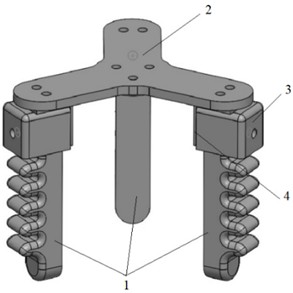

The mushroom picking flexible robotic arm designed in this study include the picking mechanical arm, chassis, industrial camera, flexible gripper, collection basket, and lifting system. Fig. 2 shows the structure of the mushroom picking robotic arm, with the flexible gripper as the core component.

The robotic arm moves along the aisles between Agaricus bisporus cultivation area, with the retractable system entering the picking unit from the side of the mushroom cultivation rack. The mechanical arm is a planar articulated robotic arm controlled by motors to rotate the arm joints. An industrial camera is positioned vertically in front of the robotic arm, capturing the coordinates of the center of Agaricus bisporus in the horizontal plane within the picking unit. A distance sensor is placed at the gripper's center to measure the height difference between the mushroom and the gripper, determining whether the gripper can grasp the mushroom. The flexible gripper at the end of the mechanical arm can enter the workspace of each point and pick mushrooms through lifting and twisting actions. The modular design of the mushroom picking robotic arm streamlines integration, reduces manufacturing costs, simplifies the installation and removal of the picking mechanism.

Fig. 1Structure diagram of planting greenhouse

Fig. 2Structure of mushroom picking flexible robotic arm: 1 – storage battery; 2 – universal wheels; 3 – lifting system control box; 4 – bottom support plate; 5 – lifting system motor; 6 – lifting system; 7 – retractable system control box; 8 – retractable system motor; 9 – mechanical arm; 10 –industrial camera; 11 – electric retractable rod; 12 – rotating cylinder; 13 –distance sensor; 14 – retractable system fixed platform; 15 – collection basket; 16 – retractable system

According to the basic parameters of the mushroom greenhouse and the requirements of picking operations, the main performance parameters of the mushroom picking robotic arm are shown in Table 1.

Table 1The main performance parameters of the mushroom picking robot

Parameter | Value | Unit |

Dimensions | 1200×1100×650 | mm |

Main arm motor power | 155 | kW |

Secondary arm motor power | 53 | kW |

Gripper width | 45-65 | mm |

Gripper height | 45-90 | mm |

Picking speed | 2 | m/s |

3. Design of robotic arm and flexible gripper

3.1. Structural design of robotic arm

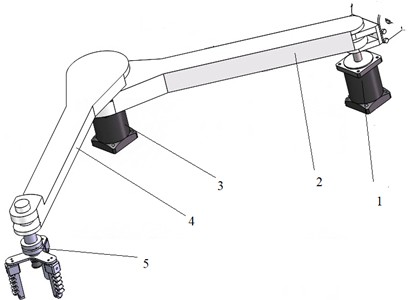

To provide sufficient picking space within the limited space between layers of the standard mushroom greenhouse, a planar joint typed robotic arm is adopted as the layout scheme for the picking arm. The planar layout scheme robotic arm has the advantages of compact structure, small size and occupying less vertical space. The entire robotic arm is connected to an -axis lead screw slider of the scalable system through the main arm and support base. The main arm links the shoulder and the elbow joints, while the secondary arm links the elbow joint to the wrist join which is equipped with a flexible gripper for picking mushrooms. The design of the robotic arm is shown in Fig. 3. This layout allows the robotic arm to exhibit both flexibility and efficiency, facilitating precise picking operations within the confined space between layers.

Fig. 3Design diagram of robotic arm: 1 – main arm motor; 2 – main arm; 3 – secondary arm motor; 4 – secondary arm; 5 – flexible gripper wrist

In the design of the mushroom picking robot, high-performance harmonic reducers are selected as the transmission devices for the main arm joint and secondary arm joint. The reduction ratio is set at 80, and high-speed closed-loop brushless DC motors are utilized to drive the harmonic reducers. An electric retractable rod is employed at the end of the robotic arm to control the vertical position of the flexible gripper, enabling precise picking actions such as descending to grab mushrooms, ascending, and placing in fixed position. This design ensures accurate motion control and stable operational performance, enabling the robot to effectively carry out the task of mushroom picking.

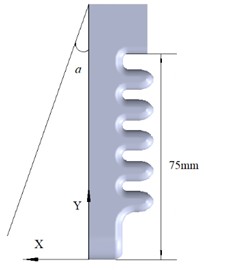

3.2. Structural design of flexible grippers

Mushroom are typically cultivated in an enclosed mushroom greenhouse where environmental parameters such as humidity, temperature, and lighting can be controlled. The picking targets of the mushroom picking robot are generally white mushrooms, with specific parameters as follows: height ranging from 45 to 90 mm, cap diameter ranging from 45 to 120 mm, cap thickness ranging from 45 to 75 mm, and stem diameter ranging from 15 to 35 mm.

The mycelium of mushrooms grows clustered on the surface of the substrate, and due to the random size and position of the mushrooms during the growth process, there is no fixed row or plant spacing. For the picking operation, the target mushrooms have a cap diameter of 45-65 mm, with a smooth, white, hemispherical surface that shows a certain degree of elasticity. The mushroom stems are approximately cylindrical in shape, with a diameter of 15-20 mm for the picking operation. Since mushrooms are relatively lightweight, only a minimal gripping force is required. When using the robotic gripper to pick mushrooms, it is essential to avoid damaging the root system of the growing substrate, which could potentially disrupt the normal growth of nearby immature mushrooms.

During the picking process with the robotic arm, the gripper descends first, with its inner side making contact with the stem of mushroom. The gripping force is generated at the fingertips to grasp the stem firmly. The gripping force is then generated at the fingertips to grasp the stem of the mushroom firmly. With a fixed angle attained through the rotation of the cylinder, the stem of mushroom is twisted off, freeing it from the substrate. Subsequently, the flexible gripper ascends along with the electric scalable rod to complete the picking action. The mushroom stem is cut at the base and then placed in the complete basket to finalize the harvest process.

Fig. 4Structure diagram of flexible gripper: 1 – fingers (5 joints); 2 – top mounting plate; 3 – outer connecting block; 4 – inner connecting plate

During the picking process, different white mushrooms exhibit varying degrees of growth direction, adhesion strength, and compression force. Traditional metal robotic grippers are ineffective in protecting the mushroom caps, and the high temperature and humidity in the environment may cause corrosion to metal fingers and components. To resolve this problem, flexible picking grippers are used to efficiently and non-destructively pick the white mushroom. The design of the an end effector, takes into consideration the spatial constraints during arm movement and the physical properties of the silicone rubber material used for constructing the flexible fingers, such as Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio. The placement of the distance sensor within the flexible gripper facilitates the accurate determination of the optimal grasping point.

The picking procedure with the flexible gripper is as follows: Upon detection by the distance sensor that the gripper is directly over the mushroom at the predetermined distance, the fingers of the flexible gripper exert pressure to grasp the mushroom stem. Subsequently, after breaking off the stem, the gripper moves it to the cutting blade located on the left side of the collection basket for trimming, and then places it into the collection basket.

4. Finite element analysis of flexible grippers

4.1. Mesh division of flexible fingers

The use of hyper-elastic material models, such as the Mooney-Rivlin and Yeoh models, has been extensively investigated across various applications involving soft materials and structures [26]. The Mooney-Rivlin model effectively captures the mechanical behavior of materials under small to moderate strains, while the Yeoh model is better suited for simulating the behavior of materials subjected to large strains. If the operational range of the flexible manipulator primarily falls within moderate strains and the material demonstrates good elastic recovery, the Mooney-Rivlin model may be a suitable choice. Conversely, for flexible manipulators that function under high strain conditions or require precise predictions of material behavior in extreme scenarios, the Yeoh model may be more appropriate, as it provides enhanced accuracy and adaptability.

The material used for the flexible gripper fingers is silicone rubber. Deformation analysis of the fingers is conducted using both the Yeoh model and the Mooney-Rivlin model. The model parameters were obtained through experimental procedures, which involved conducting standard uniaxial tensile and compression tests on silicone rubber samples to acquire stress-strain data. Subsequently, a nonlinear regression method was utilized to fit the experimental data. The parameters for the Yeoh model are set as follows: C10 = 0.6465, C20 = –0.3968, and C30 = 0.2040. For the Mooney-Rivlin model, the parameters are: C10 = 0.6976 and C01 = –0.1416. The Poisson’s ratio of the silicone rubber is 0.48, and its density is 500 kg/m3.

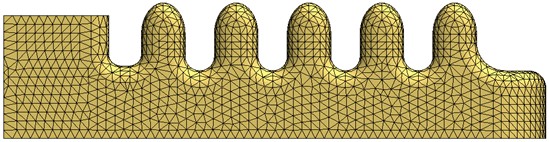

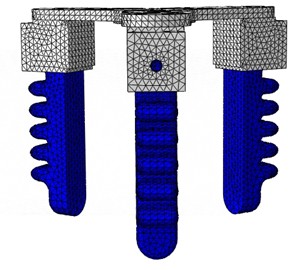

Mesh generation for the fingers plays a pivotal role in enhancing computational efficiency and convergence. Considering the material characteristics of the silicone rubber used in the flexible fingers, which acts as an approximately incompressible material, the meshing strategy should account for large bending deformations while avoiding volumetric locking. When performing elastoplastic analysis of incompressible materials, appropriate mesh element types should be chosen to prevent volume locking phenomena. Modified quadratic triangular, tetrahedral elements, non-conforming elements, and linear reduced integration elements are commonly used methods for handling elastoplastic analysis of incompressible materials. In this case, due to the complex shape of the pneumatic fingers, tetrahedral elements are chosen for meshing to better handle the intricate geometric shape. While quadratic tetrahedral elements offer higher solution accuracy, they may face challenges in convergence for large displacement problems. Therefore, linear tetrahedral elements with a four-node linear elastic tetrahedral element type (C3D4H) are chosen for meshing, as depicted in Fig. 5. This meshing approach not only ensures accurate solution results but also facilitates rapid convergence. The analysis steps are outlined as follows:

(1) Importing the Model and Setting Material Parameters. A three-dimensional model of the flexible finger is constructed and imported into ANSYS. The material properties of the flexible finger are defined as silicone rubber, with its nonlinear characteristics described by the Yeoh model and the Mooney-Rivlin model. The material parameters are derived from standard uniaxial tensile and compression tests on silicone rubber. For the Yeoh model, the parameters are C10 = 0.6465, C20 = –0.3968, and C30 = 0.2040. For the Mooney-Rivlin model, the parameters are C10 = 0.6976 and C01 = –0.1416. The Poisson’s ratio of the rubber is set at 0.48, and its density is 500 kg/m³.

(2) Assembling the Model and Adding Analysis Steps. The assembly instance type is selected as non-independent, and the analysis step type is configured as static general. To neglect the nonlinear effects of large deformations in hyperelastic materials, geometric nonlinearity is chosen. The maximum increment steps are set to 10, and the minimum and maximum increment sizes are set to 0.00001 and 1, respectively. The initial increment step is set at 0.1.

(3) Adding Boundary Conditions and Loads. Complete constraints are applied to the connection points of the flexible finger, and a pneumatic load of –0.5 to 1 MPa is applied to all inner surfaces of the air chamber.

(4) Discretizing the Mesh. The mesh properties for the flexible finger are defined as tetrahedral, with a mesh size of 0.5 mm. The element type used is C3D4H, utilizing a hybrid formulation for the simulation job.

Fig. 5Picture of flexible finger meshing

4.2. Load applied

To ensure the successful picking of mushrooms by the picking robotic arm, the flexible gripper plays a crucial role.

The deformation of the flexible gripper under loading conditions was determined by finite element analysis, and its operational range was investigated. By establishing the mechanical model of the flexible gripper, the deformation of the gripper under different air pressure conditions was simulated, and the relationship between pressure and deformation was recorded. Analysis of the results determined the required air pressure range for the flexible fingers to perform single-degree-of-freedom bidirectional bending actions, ensuring the success rate of the picking robotic arm in picking mushroom. The objective of this study is to ensure that the flexible gripper operates within the appropriate pressure range to achieve reliable picking actions, and enhance the performance and efficiency of the picking robotic arm.

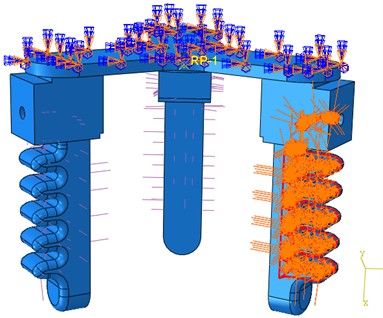

Six degrees of freedom displacement constraints are applied to the upper boundary of the picking claw model to simulate the fixed load on the flexible gripper. Pressure loads are then applied to the finger airbags to simulate the injected high-pressure gas, as shown in Fig. 6. By varying the pressure of the gas positively and negatively, both gripping and releasing conditions are simulated. Ultimately, the overall deformation of the flexible gripper is determined.

Fig. 6Simulation of high pressure gas filling operation picture

4.3. Simulation result

To explore the corresponding working pressure range for the finger's operational states, the flexible gripper model established in SOLIDWORKS was imported into ABAQUS [26] for finite element analysis. The deformation of the flexible fingers was found to be more evident in the -axis direction as compared to the -axis direction. When calculating angle , it can be considered as a right-angled triangle. The initial state of the flexible gripper is shown in Fig. 7, while Fig. 8 illustrates the deformation of the fingers.

Fig. 7Initial state diagram

Fig. 8Schematic diagram of finger deformation

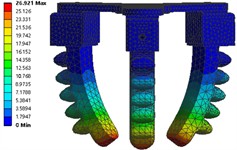

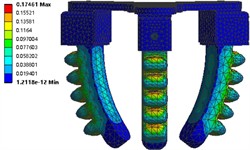

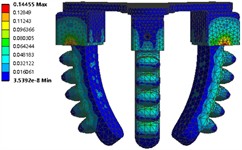

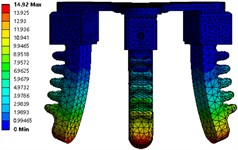

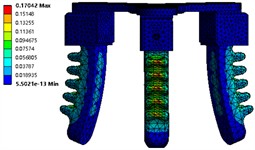

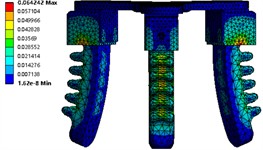

The deformation results of the two models under positive and negative pressure are recorded as follows: Under positive pressure working conditions, the deformation of the flexible fingers increases with additional pressure. Under negative pressure working conditions, the deformation of the fingers increases as pressure decreases. The displacement of the flexible finger’s tip under positive pressure working conditions can be used to grip the picking target, preventing it from slipping. When reverting to the original state under negative pressure working conditions, the grip on the picking target can be released. The flexible gripper needs to withstand certain loads during operation. Through static analysis, the stress and strain conditions were obtained, and the total deformation diagrams, equivalent elastic strain diagrams, and equivalent stress diagrams of the flexible gripper under positive and negative air pressures are presented in Fig. 9 and 10.

Fig. 9Simulation parameters of fingers under positive air pressure

a) Total deformation diagram

b) Equivalent elastic strain diagram

c) Equivalent stress diagram

Fig. 10Simulation parameters of a finger under negative air pressure.

a) Total deformation diagram

b) Equivalent elastic strain diagram

c) Equivalent stress diagram

As depicted in Fig. 9(a), the maximum deformation occurs at the fingertips. The analysis of the flexible gripper’s deformation under positive air pressure is presented in Table 2. The Yeoh model shows a maximum deformation of 26.921 mm, while the Mooney-Rivlin model shows a maximum deformation of 30.15 mm. Fig. 9(b) clearly demonstrates a relatively high equivalent elastic strain at the airbags on both sides of the flexible gripper, with the maximum value of 0.17461 meeting the requirements for picking Agaricus bisporus. In Fig. 9(c), the distribution of forces on the inner side and tips of the fingers appears to be uniform, with higher stresses observed on the outer side. The maximum stress value recorded is 0.14455, which also meets the requirements for picking Agaricus bisporus.

Table 2Finger deformation of flexible jaws by positive air pressure

Pressure (MPa) | Yeoh deformation (mm) | Mooney-Rivlin deformation (mm) | Yeoh deformation angle | Mooney-Rivlin deformation angle |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

0.2 | 5.911 | 6.77 | 4.5 | 5.15 |

0.4 | 11.39 | 12.93 | 8.63 | 9.78 |

0.6 | 16.74 | 18.79 | 12.58 | 14.07 |

0.8 | 22.13 | 24.50 | 16.43 | 18.09 |

1 | 26.921 | 30.15 | 20.29 | 21.9 |

During the negative pressure work analysis, the operation will automatically stop when the pressure reaches –0.6 MPa. Therefore, only the working states up to –0.5 MPa need to be analyzed, as shown in Table 3.

From Fig. 10(a), it can be seen that during negative air pressure operation, the maximum deformation also occurs at the fingertips, with the maximum deformation for the Yeoh model being –14.92 mm and for the Mooney-Rivlin model being –16.74 mm. As illustrated in Fig. 10(b), there is a relatively high equivalent elastic strain at the airbags on both sides of the flexible gripper, with the maximum equivalent elastic strain value reaching 0.17042. In Fig. 10(c), the distribution of forces on the inner side and tips of the fingers appears to be relatively uniform, while higher stresses occur on the outer side, with the maximum stress value being 0.064242. All these conditions meet the requirements for releasing Agaricus bisporus after picking.

Table 3Finger deformation of flexible jaws by negative air pressure

Pressure (MPa) | Yeoh deformation (mm) | Mooney-Rivlin deformation (mm) | Yeoh deformation angle | Mooney-Rivlin deformation angle |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

-0.1 | –3.257 | –3.785 | –2.48 | –2.89 |

-0.2 | –6.326 | –7.303 | –4.82 | –5.56 |

-0.3 | –9.192 | –10.59 | –6.99 | –8.03 |

-0.4 | –11.93 | –13.73 | –8.81 | –10.37 |

-0.5 | –14.92 | –16.74 | –11 | –12.58 |

Research indicates that the mechanical properties of Agaricus bisporus are as follows: The stem has an elasticity modulus of 0.92×106 Pa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.38, while the cap has an elasticity modulus of 1.01×106 Pa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.25. The shear strength of the stem is 3.20×104 N/m2 with a shear modulus of 0.33×106 Pa, and the shear strength of the cap is 7.15×104 N/m2 with a shear modulus of 0.40×106 Pa.

By considering the rheological parameters, it can be concluded that mushrooms exhibit anisotropic characteristics, with picking posing greater challenges for the stem than the cap:

where: – shear force (N); – shear strength (N/m2); – shear area (m2).

Substituting the shear strength of the mushroom stem, with the shear area set to 0.0001 m2, shear forces of 3.2 N and 7.15 N for the stalk and cap respectively are obtained. It is evident that the stem of the mushroom is comparatively easier to be sheared than the cap, as only 3.2 N of shear force is needed to break it. When the distance sensor at the center of the flexible gripper detects the specified distance for picking mushrooms, the airbag inflates to grip and twist the mushroom. As long as the shear force required to shear the mushroom exceeds 3.2 N, the process can proceed smoothly.

5. Flexible gripper control system overall program

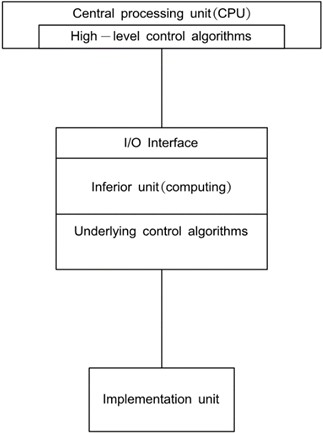

5.1. Flexible gripper control frame design

The flexible gripper as an execution part is usually commanded by the central processing unit (CPU) in a unified way, presenting a control relationship between the upper and lower levels. The control structure adopted in this paper (as shown in Fig. 11) is a distributed computing and I/O (input/output) structure, which mainly consists of a central processing unit (CPU), a lower computer, a communication protocol network and input/output devices (I/O). The central processing unit is responsible for the high-level control algorithm, and the lower computer executes the instructions and performs the underlying calculations. The execution parts perform actions according to the instructions of the lower computer, the communication protocol network realizes data transmission and instruction control, and the I/O devices are used to interact with the external environment.

Fig. 11Picking gripper control frame

The advantages of this structure lie in the allocation of the underlying computation to the lower computer, which reduces the computational burden on the central processing unit and lowers the system performance requirements; at the same time, the communication protocol network simplifies cable connections, reduces complexity and facilitates the expansion of other execution units. However, this structure also faces upper and lower level development environment differences and data transmission issues that need to be addressed in design and implementation. In addition, the rational selection and deployment of the lower level is the key to ensure the stable and efficient operation of the system.

5.2. CANopen communication framework design

The control scheme of the flexible gripper adopts a distributed computing and I/O structure, using a communication protocol network to realize the separation of upper and lower I/O interfaces. In this paper, CANopen protocol network is chosen as the communication protocol between the central processing unit and the lower computer.

CANopen is a high-level communication protocol based on the CAN bus, which is widely used for real-time serial communication, especially in industrial control and automation. Its architecture is based on control LANs and supports efficient and reliable data transmission.

The CANopen protocol consists of four sub-protocols:

1) Network Management Protocol (NMT): It is used for network management and node control, supporting state change commands and remote fault detection.

2) Heartbeat Protocol (Heartbeat Protocol): used to monitor the working status of each node.

3) Service Data Object Protocol (SDO): used for uploading/downloading object dictionaries in the network.

4) Process Data Object Protocol (PDO): used for real-time data transmission between nodes, especially suitable for immediate transmission of process data.

The communication framework for this article is shown in Fig. 12, and the driver module acts as a slave node, responsible for data exchange with the master.

Fig. 12Control system workflow diagram

5.3. Servo control

The Flexible Gripper is equipped with two internal servos, each of which is identified by a unique ID number. The servos are controlled using TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) signals, a digital signaling standard commonly used in robotics. The servos precisely control the angle of rotation based on the received TTL signals. The microprocessor sends TTL signals to the servo through the signal processing module, and after receiving commands from the central processing unit (CPU), the microprocessor controls the servo to reach a predetermined position according to the commands. After the servo reaches the target position, the microprocessor reads the status information of the servo (e.g. position and current) and returns the data to the CPU via the CANopen bus.

In this paper, we also design a set of flexible gripper grasping judgment process, based on the servo current and position feedback to determine whether the target mushroom stalk is successfully grasped. As shown in Fig. 13, when the flexible gripper completes the grasping operation, it enters the blocking mode, and the servo current reaches twice the normal operating current. The microprocessor determines whether it is in the blocking state through the current feedback, if so, it is considered that the grasping is successful; if not, it is considered that the grasping fails. However, the flexible gripper may grab other objects, not necessarily the target mushroom stalk. Therefore, after the initial judgment of successful grasping, it is still necessary to confirm whether it is the target mushroom stalk.

According to the cap and stalk height data provided in Section 3.2, if the servo successfully grabs the target stalk, the servo position should be within the height range of the stalk. The microprocessor further confirms whether the grasping is successful by reading the servo position and determining whether it is within this range. If the servo position is within this range, it is judged as successfully grasping the target mushroom stalk; otherwise, it is judged as grasping failure.

6. Experimental validation

6.1. Sensing system and data acquisition

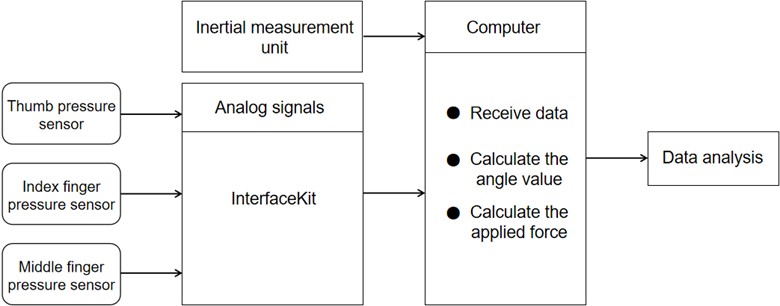

To measure the force applied by each flexible finger to the cap of the Agaricus bisporus during harvesting, thin-film force sensors were attached to the thumb, index finger, and middle finger. The maximum range of these sensors is 20 N, with a measurement calibration error less than 0.1 N. During this process, the fingertips generate a gripping force that clamps the stem of the Agaricus bisporus, and after the rotating cylinder turns at a fixed angle, it causes the mushroom stem to twist and break. This process involves changes in the orientation of the mushroom itself, which is measured using a high-precision six-axis inertial measurement unit (IMU), model WT61P, installed within a base equipped with a securing pin that is inserted into the upper surface of the mushroom cap.

Fig. 13Data acquisition flowchart

During harvesting, the sensors attached to the thumb, index, and middle fingers convert the forces into analog signals, which are then fed into a computer via an InterfaceKit module through a serial port for storage. The obtained data is used to calculate the applied force using Eq. (2):

where: – shear force (N); voltage ratio – the ratio of output voltage to input voltage in a transformer; – acceleration due to gravity (m/s2).

The IMU WT61P measures the angular changes around three axes of the mushroom during picking through its internal gyroscope and accelerometer. The collected signals are input into the computer for real-time display and recording of the angles. The data acquisition process is illustrated in Fig. 13.

6.2. Flexible gripper shear force, picking angle, and time analysis

In this study, the Agaricus bisporus mushrooms used were cultivated in a mushroom-growing greenhouse located in Shen County, Shandong, where the growing bed racks are arranged in multiple layers. During harvesting, mature mushrooms of similar size that mostly grow individually or without interference from neighboring mushrooms were selected. Prior to picking, thin-film force sensors were attached to the ends of the flexible grippers, and an inertial measurement unit was installed on the cap of the targeted mushroom to facilitate the collection of data related to shear force, picking angle, and picking time.

During the experiment, three growing racks within the greenhouse were chosen for harvesting tests when the Agaricus bisporus reached the same maturity level. The tests recorded the shear forces experienced by the stem and cap during the harvest, as well as changes in angle and picking time. Throughout the operation, the flexible gripper performed stably without any other anomalies. Observations of the obtained data revealed that the average shear force experienced by the stems during harvesting was 3.1 N, which is lower than the 7.3 N experienced by the caps (as shown in Table 4), results that are largely consistent with the simulation outcomes. During the picking process, fluctuations in shear force and angles occurred; this is attributed to the relatively slippery surface of the mushroom caps in the growing greenhouse, causing slippage of the flexible gripper on the cap surface leading to failed picks.

Table 4Picking parameters during harvesting with flexible grippers

Shear force on stem / N | Shear force on cap / N | Picking angle (-axis) / (°) | Picking time / s | |

Rack No.1 | 2.9 | 7.3 | 86.6 | 3.1 |

Rack No.2 | 3.4 | 7 | 82.3 | 3.3 |

Rack No.3 | 3.0 | 7.6 | 85.1 | 3.1 |

mean | 3.1 | 7.3 | 84.7 | 3.17 |

6.3. Flexible gripper picking success analysis

The maturation cycle of Agaricus bisporus is 30 to 40 days under suitable growth conditions, and the cap and stalk diameters vary with the change of growth time, which may affect the picking effect of the designed gripper jaws. In order to verify the picking stability and safety of the gripper at different growth stages, a picking test was conducted under the above conditions. In the experiment, Agaricus bisporus buds with cap diameter of about 1 cm were selected and picked after 34, 36, 38 and 40 days of mushroom growth, with four groups of 20 samples each, totaling 80 mushrooms. The average values of cap and stipe diameters at different growth stages are shown in Table 5. The test method was as follows: after confirming the picking target, move the picking jaws to the target position, grasp the stipe and rotate to separate the mushrooms, and the picking speed was 2 m/s. The picking success rate was recorded and the influencing factors were analyzed, and the results of the test are shown in Table 6.

According to the data in the table, the clamping jaw designed in this paper successfully picked 68 mushrooms and failed 12, with a picking success rate of 85 %. Among them, for mushrooms grown for 36 and 38 days, the picking success rate was higher, 90 % and 95 %, respectively; while for mushrooms grown for 34 and 40 days, the success rate was relatively lower, 80 % and 75 %, respectively. At 34 days of growth, the mean value of stipe diameter was 12.1 mm, while at 40 days of growth, the mean value of stipe diameter was 15.4 mm, which resulted in a lower picking success rate due to the slippage of the jaws when holding these mushrooms. Therefore, the designed jaws were most effective in picking mushrooms with cap diameters of 59.6 mm to 64.5 mm and stipe diameters of 12.8 mm to 13.6 mm at the 36 to 38 days growth stage. In addition, this growth stage is also the most suitable period for picking Agaricus bisporus mushrooms.

Table 5The cap diameter and stipe diameter of Agaricus bisporus at different days of growth

34 days | 36 days | 38 days | 40 days | |

Diameter of mushroom cap (mm) | 55.3 | 59.6 | 64.5 | 72.1 |

Stalk diameter (mm) | 12.1 | 12.8 | 13.6 | 15.4 |

Table 6Picking grasper success rate statistics

Days of growth | Number of successful picks | Number of failed picks | Success rate |

34 | 16 | 4 | 80 % |

36 | 18 | 2 | 90 % |

38 | 19 | 1 | 95 % |

40 | 15 | 5 | 75 % |

7. Conclusions

This passage presents a flexible mushroom picking robotic arm with autonomous lifting and extending capabilities, designed for the specific characteristics of mushrooms grown in greenhouse environments and their vulnerability character during picking. The robotic arm can move within the restricted space of the greenhouse and perform damage-free picking mushrooms, thereby enhancing the efficiency of picking operations.

The design of the mechanical arm and flexible gripper of the device takes into consideration the growth parameters of mushrooms and the physical properties of the silicone rubber material used to make the flexible fingers, such as Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio. ABAQUS software is used to simulate clamping and releasing conditions by adjusting the pressure inside the flexible gripper's airbags, using the Yeoh model and the Mooney-Rivlin model as research models. Tetrahedral linear elements (C3D4H) are used for meshing, with mesh refinement applied to ensure accurate and quick convergence.

The finite element analysis reveals that under positive pressure, the maximum deformations of the flexible gripper based on the Yeoh model and the Mooney-Rivlin model are 27.74 mm and 30.15 mm, The maximum equivalent elastic strain was 0.17461 and the maximum stress was 0.14455, which met the requirements of picking Agaricus bisporus. Under negative pressure, the maximum deformations according to the Yeoh model and the Mooney-Rivlin model are –14.58 mm and –16.74 mm, The maximum equivalent elastic strain was 0.17042 and the maximum stress was 0.064242, both of which met the requirements of releasing and picking Agaricus bisporus. In the experimental verification of the mushroom planting greenhouse in Shen County, Shandong, a sensing system was built to measure the force exerted by each flexible finger on the mushroom cap, the picking angle and the picking time during the picking process of Agaricus bisporus, and the data obtained were basically the same as the simulation results, and analyzed the picking success of the flexible gripper, so the flexible gripper structure met the actual picking requirements of Agaricus bisporus, and proved that the designed mushroom picking manipulator had good stability and feasibility.

References

-

S. Budzyńska et al., “Mycoremediation of flotation tailings with agaricus bisporus,” Journal of Fungi, Vol. 8, No. 8, p. 883, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/jof8080883

-

F.-H. Zhai, Y.-F. Chen, Y. Zhang, W.-J. Zhao, and J.-R. Han, “Phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of wheat fermented with Agaricus brasiliensis and Agaricus bisporus,” FEMS Microbiology Letters, Vol. 368, No. 1, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnaa213

-

P. Salachna, Łopusiewicz, A. Wesołowska, E. Meller, and R. Piechocki, “Mushroom waste biomass alters the yield, total phenolic content, antioxidant activity and essential oil composition of Tagetes patula L.,” Industrial Crops and Products, Vol. 171, No. 1, p. 113961, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113961

-

A. Hassainia, H. Satha, and S. Boufi, “Chitin from agaricus bisporus: extraction and characterization,” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Vol. 117, No. 1, pp. 1334–1342, Oct. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.172

-

W. Chen, Z. Cai, Z. Zheng, M. Chen, and J. Dai, “Localization development and process improvement of aseptic breathable bags of Agaricus bisporus,” Southeast Gardening, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 464–471, 2024, https://doi.org/10.20023/j.cnki.2095-5774.2024.06.003

-

N. Wang, Y. Wang, F. Wang, W. Feng, Q. Zhang, and Q. Liu, “Key Points of Factory Cultivation Techniques for agaricus bisporus,” (in Chinese), Agricultural Science and Technology Communication, No. 5, p. 296, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6400.2021.05.100

-

Q. Tang, J. Huang, L. Sang, X. Shen, and F. Cai, “Harvesting techniques for factory cultivated agaricus bisporus,” (in Chinese), Edible Fungi, Vol. 42, No. 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-8357.2020.05.014

-

K. Tao, Z. Wang, J. Yuan, and X. Liu, “Design of a novel end-effector for robotic bud thinning of Agaricus bisporus mushrooms,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, Vol. 210, No. 10, p. 107880, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.107880

-

K. Mollazade, “Non-destructive identifying level of browning development in button mushroom (agaricus bisporus) using hyperspectral imaging associated with chemometrics,” Food Analytical Methods, Vol. 10, No. 8, pp. 2743–2754, Feb. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-017-0845-y

-

M. Zhong, R. Han, Y. Liu, B. Huang, X. Chai, and Y. Liu, “Development, integration, and field evaluation of an autonomous Agaricus bisporus picking robot,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, Vol. 220, No. 10, p. 108871, May 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.108871

-

T. A. Pool and R. C. Harrell, “An end-effector for robotic removal of citrus from the tree,” Transactions of the ASAE, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 0373–378, Jan. 1991, https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.31671

-

B. Arad, “Development of a sweet pepper harvesting robot,” Journal of Field Robotics, Vol. 37, No. 6, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3030/644313

-

X. Cheng et al., “A halation reduction method for high quality images of tomato fruits in greenhouse,” Engineering in Agriculture, Environment and Food, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 200–206, Oct. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eaef.2015.10.001

-

S. Hayashi, S. Yamamoto, S. Saito, Y. Ochiai, Y. Nagasaki, and Y. Kohno, “Structural environment suited to the operation of a strawberry-harvesting robot mounted on a travelling platform,” Engineering in Agriculture, Environment and Food, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 34–40, Jan. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1881-8366(13)80015-8

-

P. Jedrzejowicz and I. Wierzbowska, “Implementation of the mushroom picking framework for solving flexible job shop scheduling problems in parallel,” Procedia Computer Science, Vol. 207, pp. 292–298, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.09.062

-

C.-P. Lu, J.-J. Liaw, T.-C. Wu, and T.-F. Hung, “Development of a mushroom growth measurement system applying deep learning for image recognition,” Agronomy, Vol. 9, No. 1, p. 32, Jan. 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9010032

-

B. Gu, C. Ji, H. Wang, G. Tian, G. Zhang, and L. Wang, “Design and experiment of intelligent mobile fruit picking robot,” (in Chinese), Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 153–160, 2012, https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2012.06.028

-

H. Nie, “Research on the vibration characteristics of mechanical harvesting of blueberry plants and the design of harvesting experiment platform,” (in Chinese), Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2020.

-

E. J. van Henten et al., “An autonomous robot for harvesting cucumbers in greenhouses,” Autonomous Robots, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 241–258, Jan. 2002, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020568125418

-

J. Zhang, D. He, and Z. Zhang, “Design of adaptive robust tracking control algorithm for picking robot,” (in Chinese), Journal of Agricultural Mechanization Research, Vol. 31, No. 12, pp. 10–14, 2009, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-188x.2009.12.003

-

Z. Li, Y. Zhang, Y. Geng, Y. Xie, and J. Sun, “Packaging and food machinery,” (in Chinese), Packaging and Food Machinery, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 70–74, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-1295.2023.01.011

-

C. Liu, T. Zhang, and L. Yang, “Design of end effector for eggplant picking robot,” (in Chinese), Journal of Agricultural Mechanization Research, Vol. 30, No. 12, pp. 62–64, 2008, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-188x.2008.12.019

-

Y. Zhou, Q. Li, H. Li, and R. Wang, “Transactions of the Chinese society of agricultural engineering,” (in Chinese), Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 27–32, 1995, https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1002-6819.1995.04.007

-

Y. Zhou, D. Zhang, and Y. Zhang, “Research algorithm of multi-mobile robot path planning--based on distributed real-time simulation system,” (in Chinese), Journal of Agricultural Mechanization Research, Vol. 42, No. 12, pp. 205–209, 2020, https://doi.org/10.13427/j.cnki.njyi.2020.12.037

-

Qiu Jianxin, “Object detection algorithm for mushroom picking robot,” (in Chinese), Journal of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, 2021, https://doi.org/10.16853/j.cnki.1009-3575.2021.02.017

-

R. K. Venkatesh and R. Malayalamurthi, “Assessment on assorted hyper-elastic material models applied for large deformation soft finger contact problems,” International Journal of Mechanics and Materials in Design, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 299–305, Aug. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10999-011-9167-1

-

N. Ye, C. Su, and Y. Yang, “Free and forced vibration analysis in Abaqus based on the polygonal scaled boundary finite element method,” Advances in Civil Engineering, Vol. 2021, No. 1, pp. 1–17, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7664870

-

J. Li, “Design of shiitake mushroom stalk gripping-screwing picking hand claw,” (in Chinese), Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2024.

About this article

The authors would like to thank the Northeast Forestry University (NEFU), the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province. The research topic was supported by the Natural Science Foundation Project of Heilongjiang Province (Grant No. LH2020C047), the Innovation Training Program of Northeast Forestry University (Grant No. 202310225190).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Haining Xu: modeling and writing. Ying Xin: conceptualization and supervision. Zihan Wang: simulation. Bingheng Li: experiments. Siyi Chen: analyzing research data.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.