Abstract

In this paper, we present some improvements to the convergent cross mapping (CCM) algorithm for detecting causality in uni-directionally connected chaotic systems. The basic concept of the CCM algorithm is that the causal influence of system on system appears as mapping of the neighbouring states in the reconstructed -dimensional manifold, , to the neighbouring states in the reconstructed -dimensional manifold, , and this effect is evaluated using the correlation coefficient between the estimated and observed values of . We proposed a composite indicator of causality as the ratio between the correlation coefficient and the Shannon entropy of the distribution of the residuals between the estimated and observed values of . Application of the proposed approach to four master-slave Rössler and Lorenz systems and real-world data showed that the new algorithm allowed a slight increase in capability to reveal the presence and direction of couplings.

1. Introduction

Quantification of the causal effects between simultaneously observed systems from the analysis of time series recordings is essential in many scientific fields, including economics, climatology, ecosystems, electrical activity of the brain, or cardiorespiratory relations. Estimating the interdependence between the observed variables provides valuable knowledge regarding the processes that generate time series [1]. The Granger causality method [2] is the most well-known and principal method for identifying directional interactions between variables from their time series, and many modifications and extensions of the Granger causality test has been developed. The Granger test focuses on determining whether one time series is useful in forecasting another. If useful, the first system causally affects the second system. The conventional Granger’s causality test is based on autoregressive models and is particularly useful in stochastic linearly interconnected systems [3]. However, its appropriateness of direct application to nonlinear systems depends on the specific problem to be analyzed [4-6]. Therefore, new approaches have been proposed, including nonlinear extensions of Granger’s causality [4], transfer entropy [7], conditional mutual information [8] and measures evaluating distances of conditioned neighbors in reconstructed state spaces [9-13], to name a few. In 2012, Sugihara et al. [5] introduced another method based on state space reconstruction. The method was called convergent cross-mapping (CCM) and involves evaluating distances between conditioned neighbours in reconstructed state spaces and tests for causation between the driver (“master”) system and the driven (“slave”) system Y, by measuring the extent to which the historical states of reconstructed state space, , can reliably estimate states of reconstructed state space, . Similarity between points, , and estimates, , is evaluated by assessing their correlation. To infer the direction of coupling, the opposite direction must also be assessed. Then, the direction of coupling is inferred based on asymmetries emerging from the calculations of the two possible causal directions.

In this paper, we propose a simple improvement to the CCM method by introducing a composite parameter for inferring the direction of causation composed of two components: (1) the correlation coefficient between the cross-mapped and observed values of the reconstructed state space, and (2) Shannon entropy of the distribution of the residuals between the cross-mapped and observed values of the reconstructed state space.

2. Convergent cross mapping

CCM [5, 14] is a method for detecting causality between two systems represented by time series. CCM is based on Takens’ embedding theorem, exploiting the geometry of attractors of coupled dynamical systems and constructs a map between mutual neighborhoods in state spaces of the coupled dynamical systems under study.

Let , and be two time series of finite length . To establish cross mapping from to , first we reconstruct the attractor manifold as a set of -dimensional vectors [15] for to , i.e., , where is the embedding dimension, is the time delay, and denotes the transpose of a real matrix. We find the nearest neighbors of in and denote their time indices (from the closest to the farthest) by . These indices will be used in the construction of the cross mapping of for , by:

where , and is the Euclidean distance between vectors and . The cross mapping from Y to X is defined analogously. The skill of cross-map estimates is indicated by the correlation coefficient between and (or between and , respectively). Sugihara et al. [5] declare in the supplement: “If and are dynamically coupled, the nearest neighbors of should identify the time indices of corresponding nearest neighbors on . As increases, the attractor manifold fills in and the distances among the nearest neighbors shrinks. Consequently, should converge to and should converge to . In this way, we use convergence of the nearest neighbors to test whether there is a correspondence between states on and states on ”. Cross-mapping that converges in only one direction is the criterion for unidirectional causality. One of the fundamental concepts of CCM is that when causation is unilateral, ( drives ), then it is possible to estimate from , but not from . It follows that a high value of the correlation coefficient between and comparing to the value of the correlation coefficient between and indicates that system drives system . This runs counter to Granger’s intuitive scheme. For more details on the CCM method see [5, 14, 16, 17].

3. Description of the algorithm

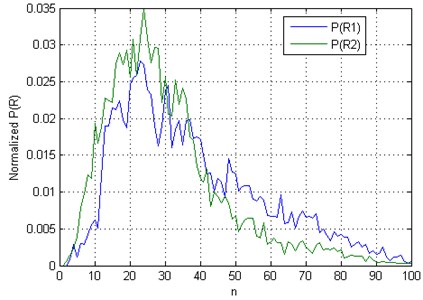

The simulation results obtained from the CCM method applied to uni-directionally coupled non-identical oscillators ( drives ) shows that probability distribution of the residuals taken as the Euclidean distance between manifold and manifold obtained by cross mapping using a manifold , and the Euclidean distance between manifold and manifold obtained by cross mapping using a manifold , differs. More specifically, the probability distribution of has a taller, narrower shape (Fig. 1). It is therefore reasonable to combine the Shannon entropy of the probability distributions of or , and the corresponding correlation coefficient to enhance the inference of the direction of instantaneous causality. Furthermore, we compute the relationship between vectors of the manifold and its cross-mapped estimate and between vectors of the manifold and its cross-mapped estimate , by determining the 2D correlation coefficient, and introduce interdependence measures and as:

where is the 2D correlation coefficient between vectors of the manifold and its cross-mapped estimate , is the 2D correlation coefficient between vectors of the manifold and its cross-mapped estimate , is the Shannon entropy of the probability distribution of , and is the Shannon entropy of the probability distribution of .

Fig. 1Example of the probability distribution of the Euclidean distances RMX,MX^|MY and RMY,MY^|MX

4. Results

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the cross-mapping evaluated by the proposed interdependence measures (), we compared it with the cross-mapping evaluated using the correlation coefficient () on four test examples of uni-directionally connected chaotic Rössler and Lorenz-type systems that were coupled with variable coupling strengths. In the examples used in this paper, the possibility of correlation instead of causation was excluded, and therefore the aspect of convergence was not used. The first and second datasets originated from the coupling of two Rössler systems [17], which were coupled via a one-way driving relationship between variables of the driving system and variable of the responsive system:

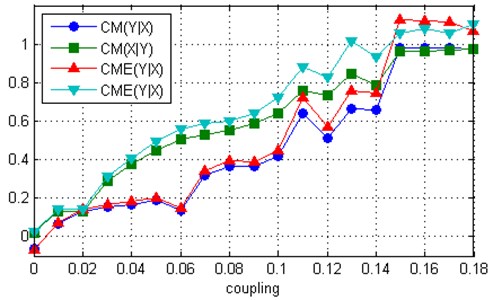

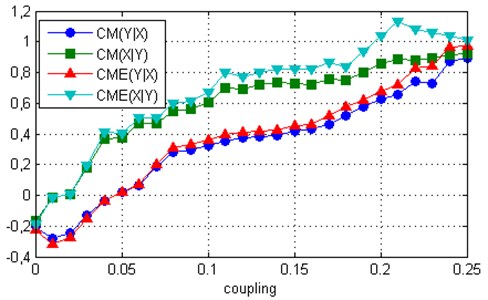

where 1.015, 0.985 and 1.075, 1.0. The coupling strength was chosen from 0 to 0:25 with the step 0:01. The data were generated by Runge-Kutta integration with a step size of 0.1. The first 2000 data points were discarded. The total number of obtained data was 14000 and this resulted in around 60 samples per one average orbit around the attractor. The causal relationship between the two systems was calculated using 7000 time-delayed vectors of and with a time delay equal to 3 and embedding dimension of 7. Eight nearest neighbours were used. All data processing and analyses were performed using Matlab software (MathWorks, Natick, MA) by adopting the ideas from reference [18], among others. Consequently, we denoted the direction from to as and the direction from to as . Taking, for example, the measure CM: if drives , the measure is expected to be higher than . As we can see from Fig. 2, both CME and CM measures show that drives until the onset of synchronization. The effect of the entropy contribution in the direction is little, but is considerable in the direction, especially at moderate and high coupling strengths. As a result, the gap between and becomes larger, compared to the gap between and , i.e. the direction of causation can be determined more reliable. Furthermore, in the case of the coupled Rössler systems with 1.075, 1.0, the independent-samples t-test showed that this difference between gaps across all coupling strengths is near to statistical significance ( 0.0866).

Fig. 2Measures CME and CM computed for two uni-directionally coupled Rössler systems: a) ω1= 1.015, ω2=0 .985, b) ω1= 1.075, ω2= 1.0

a)

b)

The third and fourth datasets originated from the coupling of two Lorenz systems [17], which are coupled via one-way driving relationship between variables of the driving system and variable of the responsive system:

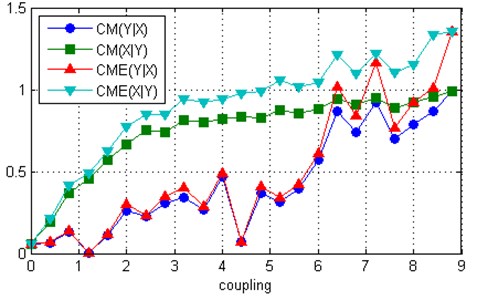

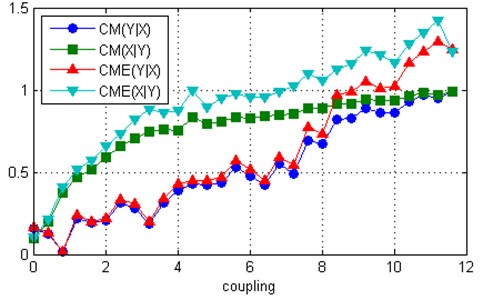

where 28,5, 27.5 and 39, 35. The coupling strength was chosen from 0 to 11.6 with a step size 0:4. The data were generated using the Matlab solver of ordinary differential equations ode45. The first 2000 data points were discarded. The total number of obtained data was 14000 and the causal relationship between the two systems was calculated using 7000 time-delayed vectors of and , with a time delay equal to 3 and embedding dimension of 7. As we can see from Fig. 3, the results are similar to the coupled Rössler systems, although the effect of entropy is greater.

Fig. 3Measures CME and CM computed for two uni-directionally coupled Lorenz systems: a) ω1= 28.5, ω2= 27.5, b) ω1= 39, ω2= 35

a)

b)

To demonstrate the performance of the proposed algorithm on real-world data, we applied the algorithm for the quantification of coupling between respiration and heart rate variability (HRV) because is well known that HRV is strongly related to respiration. For this purpose, we used data from the Fantasia database (https://physionet.org/physiobank/database/fantasia/). The data that are free of artifacts were acquired from 12 young subjects. The R-peaks of the electrocardiogram (ECG) signal were detected by means of a threshold method and the RR time series were obtained. In this study, we removed the mean of every RR time series either as of every respiration signal so that they oscillate around zero. The independent-samples t-test showed a statistically significant ( 0.0097) difference between and and much more statistically significant ( 0.000454) difference between and .

5. Conclusions

A simulation involving examples of uni-directionally connected chaotic of Rössler and Lorenz-type systems and real-world time series shows that the proposed substitutions in the CCM method reinforce the asymmetries between the calculations of the two possible causal directions and thus improve determination of the presence and direction of coupling, and also detection of the onset of full synchronization in uni-directionally connected chaotic systems.

References

-

Papana A, Kyrtsou C., Kugiumtzis D., Diks C. Simulation study of direct causality measures in multivariate time series. Entropy, Vol. 15, 2013, p. 2635-2661.

-

Granger C. W. J. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, Vol. 37, 1969, p. 424-438.

-

Krakovska A., Hanzely F. Testing for causality in reconstructed state spaces by an optimized mixed prediction method. Physical Review E, Vol. 94, 2016, p. 052203.

-

Chen Y., Rangarajan G., Feng J., Ding M. Analyzing multiple nonlinear time series with extended Granger causality. Physics Letters A, Vol. 324, 2004, p. 26-35.

-

Sugihara G., May R., Ye H., Hsieh C.-H., Deyle E., Fogarty M., Munch S. Detecting causality in complex ecosystems. Science, Vol. 338, 2012, p. 496-500.

-

Lusch B., Maia P. D., Kutz J. N. Inferring connectivity in networked dynamical systems: challenges using Granger causality. Physical. Review E, Vol. 94, 2016, p. 032220.

-

Schreiber T. Measuring information transfer. Physical Review Letters, Vol. 85, 2000, p. 461-464.

-

Paluš M., Vejmelka M. Directionality of coupling from bivariate time series: how to avoid false causalities and missed connections. Physical Review E, Vol. 75, 2007, p. 056211.

-

Arnhold J., Grassberger P., Lehnertz K., Elger C. E. A robust method for detecting interdependences: application to intracranially recorded EEG. Physica D, Vol. 134, Issue 4, 1999, p. 419-430.

-

Quiroga R. Q., Kraskov A., Kreuz T., Grassberger P. Performance of different synchronization measures in real data: a case study on electroencephalographic signals. Physical Review E, Vol. 65, 2002, p. 041903.

-

Andrzejak Kraskov R. G. A., Stögbauer H., Mormann F., Kreuz T. Bivariate surrogate techniques: Necessity, strengths, and caveats. Physical Review E, Vol. 68, 2003, p. 066202.

-

Smirnov D. A., Andrzejak R. G. Detection of weak directional coupling: phase-dynamics approach versus state-space approach. Physical Review E, Vol. 71, 2005, p. 036207.

-

Chicharro D., Andrzejak R. G. Reliable detection of directional couplings using rank statistics. Physical Review E, Vol. 80, 2009, p. 026217.

-

Coufal D., Jakubík J., Jajcay N., Hlinka J., Krakovská A., Paluš M. Detection of coupling delay: a problem not yet solved. Chaos, Vol. 27, 2017, p. 083109.

-

Kantz H., Schreiber T. Nonlinear Time Series Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004.

-

Ye H., Deyle E. R., Gilarranz L. J., Sugihara G. Distinguishing time-delayed causal interactions using convergent cross mapping. Scientific Reports, Vol. 5, 2015, p. 14750.

-

Krakovská A., Jakubík J., Budáčová H., Holecyová M. Causality Studied in Reconstructed State Space. Examples of uni-directionally connected chaotic systems. 2016, https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.00505.

-

Jakubik J. Convergent Cross Mapping. Version 1.3, http://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/ fileexchange/52964-convergent-cross-mapping.