Abstract

Local damage on concrete slab subjected to a contact explosion includes explosive cratering on the front face and spalling or perforating on the back face. It is a subject that has been studied by many investigators for many years for many purposes. However, computational methods on explosive spallation or perforation are rare while they are significant for the design of warhead, the protective structure and engineering blasting. In this paper, the dynamic behavior of material was described by rigid-plastic model, and the material resistance of concrete slab subjected to contact explosions was derived by utilizing limit equilibrium theory. Combined with the initial and boundary conditions, the formulae of the threshold thickness have been derived, which can predict the categories of local damage on concrete slab under contact explosion loads. Besides, a non-dimensional impact factor was derived, which reflects the integrated nature of explosive sources and material resistance. Finally, analysis study of the results of numerical simulation and the derived equations proved the rationality of the proposed calculation methods.

1. Introduction

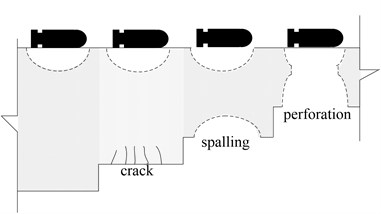

The analysis of concrete structures against short duration dynamic loads is a topic of extensive study in recent several decades [1]. Local damage of slabs will occur, when they are subjected to intense loads generated by an explosion or penetration. When shock waves spread to the back surface, tensile waves, causing the structure to spall on backside, forms concrete fragments of different sizes. Damage occurs throughout the thickness of members: compression or shock loads generate explosion craters and back faces rupture in slab members. When particularly thin concrete slabs suffer an explosion, punching failure arises. As shown in Fig. 1 [2, 3], there are many correspondences and similarity between the explosive damage and impact damage of slabs.

Fig. 1Local damage of slabs under intense loads

a) Explosive damage

b) Impact damage

In 1914, spalling damage was first observed by Hopkinson [4]. In the early 1950s, Reinhardt [5] observed spalling in a series of contact detonation tests of high explosives and metal plates. Since then, the Ballistic Research Laboratory (BRL) of the United States, in the 1960s, proposed the BRL formula for spalling thickness [6]: the spalling thickness is twice that of the perforations in a concrete member. In 1976, Glenn also obtained, using stress-intensity theory, triangular load distributions, spalling parameters and shockwave speeds. In 1979, Nikiforov et al. [7] obtained a theoretical solution for these parameters. In 1982, Haldar et al. [8], from a dimensional perspective, pointed out that one side of the NDRC formula is non-dimensional, while there is a lack of dimension on the other side, for which they introduced a non-dimensional parameter called the impact factor. Differing from Haldar, Hughes [9] defined an impact coefficient by using the tensile impact factor of concrete as follows. Li Q. M. and Chen X. W. [10, 11] also introduced a dimensionless impact factor to predict penetration depth into several mediums subjected to a normal impact of a non-deformable projectile. Therefore, there are lots of methods to calculate spallation and perforation effects caused by projectile impact or penetration, but computational methods on explosive spallation or perforation are rare. The explosive spalling thickness of slabs under air-blast of bomb can be found by using the “Protective Structure Design Manual” (PCDM) [12]. But this formula does not apply to computation of damage in contact explosions. In 1996, Wierzbicki T. and Nurick G. N. [13] investigated experimentally and theoretically the response of thin clamped plates to a localized impulsive load to determine the location of tearing failure and the threshold impulse to failure. In their theoretical development, the plate was modelled as a rigid-plastic membrane. In 2006, Luccionia B. M. and Luege M. [14] investigated the behaviour of concrete pavements subjected to blast loads produced by the detonation of high explosive charges above them. Some conclusions about the effect of the blast load on the concrete slab and about different tools available for the analysis of this type of problem were stated. In recent years, scholars have proposed a number of more applicable formulae and methods of calculating explosive loads and designing protective structures. For example, Wang M. Y. et al. [15] provided a design method for steel-fibre reinforced concrete shelter plates under contact explosions; Zhang X. B. et al. [16] conducted explosion tests to assess the design thickness of reinforced concrete slabs using similarity theory and numerical methods, and they also gave the test data and analysis of the phenomenon, and finally they established an empirical method to calculate spalling thickness. Lastly, scholars always investigate the response or damage of concrete slabs under explosive loading by combining field experiments and numerical simulation [17, 18]. Li Jun and Hao Hong [19] carried out a series of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) slabs tests to determine their response under explosive loading conditions, and test results verified the effectiveness of UHPC slabs against blast loads. However, they cared more about central deflection of the slabs which cannot reflect the local damage of slabs. The theoretical analysis methods discussed in references [2, 3] were based on some simplified assumptions and their application scope is limited to light and moderate spall damage. However, these results cannot be used to distinguish the damage caused by spalling, perforating, and punching. Spall is also dependent upon the stress change during the stress wave propagation and the dynamic properties of the concrete material under high strain rate. In order to give accurate spall damage analysis, the resistant force from the material dynamic bond, shear and mechanical interlock should also be carefully considered. Until now, there are still uncertainties about these parameters.

Accordingly, this research regarded the thicknesses of spalling and perforation as two kind of threshold thicknesses. Under circumstances in which the blast loading is fixed, when the material is thicker than the threshold thickness of spalling, only compressive explosion craters occur on the front-face of the structure, explosive collapse does not occur. And when the thickness of the material lies between the threshold values for spalling and perforation, explosive collapse occurs. When the material thickness is less than the threshold thickness of perforation, explosive failure over the entire section depth occurs. Therefore, the key question is how to determine the explosive effects on threshold parameters. Through theoretical analysis, formulae for two types of threshold thickness were deduced, and then their efficacy was analysed.

2. Basic principles and model assumptions

2.1. Model assumption and initial condition

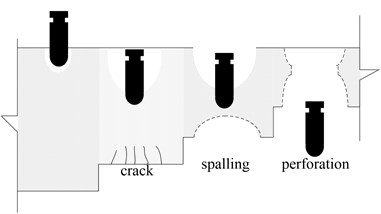

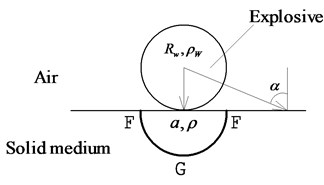

According to local damage tests on concrete slabs under explosive loads, as shown in Fig. 2 [20], there are some typical phenomena: for a thick slab, shown as Fig. 2(a), there will be a compression crater on the front-face when it is subject to a contact explosion, but there will not be any irreversible deformation on the back-face. This kind of phenomenon is called explosive cratering, and it is not necessary to consider reflective wave tension effects from the back-face of the thick slab. For a slab which is not thick enough (Fig. 2(b)), when it is subjected to a contact explosion, a compression crater will form on the front-face and a spalling crater forms on its back-face, but they are isolated from each other. This is known as spalling. For a thin slab (Fig. 2(c)), a compression crater forms on the front-face and a spalling crater forms on the back-face: the two are mutually connected. This kind of phenomenon is known as explosive perforation.

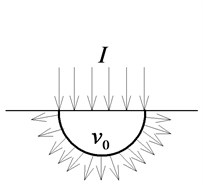

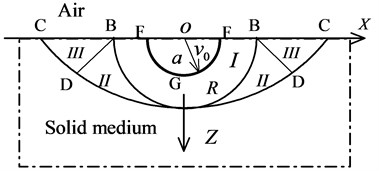

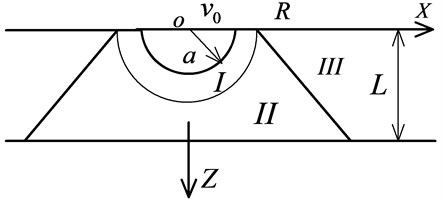

A model which depicts the impulse on the surface of a medium under contact explosion load is shown in Fig. 3. To make the mathematics tractable, we will make some simplifying assumptions:

a) The chemical reaction is completed instantly, and shock waves are quasi-instantaneous jumps in all the variables, from their initial, to final, states.

b) The radius of the spherical charge is Rw, and the density of the charge is ρw. It is in contact with the intended concrete targets.

c) Under contact explosive loads the concrete will reach a plastic state instantly and dissipate explosive energy through large deformation. Compared with the plastic deformations suffered, the elastic deformation can be ignored.

d) The impulse of the explosive detonation transmitted to the target is I, and it is firstly transmitted as a hemispherical distributed impulse (over the FGF area), which is named as initial expansion body.

Fig. 2Photographs of local damage tests on concrete slabs under explosive loads [20]

![Photographs of local damage tests on concrete slabs under explosive loads [20]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/17074/17074-img3.jpg)

a) Cratering on the front-face

![Photographs of local damage tests on concrete slabs under explosive loads [20]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/17074/17074-img4.jpg)

b) Spalling on its back-face

![Photographs of local damage tests on concrete slabs under explosive loads [20]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/17074/17074-img5.jpg)

c) Perforation

Fig. 3The impulse on the surface of medium under contact explosive loads

a)

b)

According to the law of the conversation of momentum, the vertical impulse of the detonation is equal to the vertical momentum of the initial expansion body:

where, M denotes the mass of the initial expansion body, and M=23πρa3; ρ denotes the density of target; v0 denotes the radial velocity thereof.

We assumed that the dimensions of the target are much bigger than the radius of the charge, and the kinetic energy can be written as:

Based on the conservation of energy, the relationship between the initial expansion body and the effective explosive energy can be shown to be as follows [21]:

where, Qv denotes the specific energy coefficient of the explosive, η is the fractions of energy radiated into the target, which can be acquired as follow.

The theoretical solution of the problem of radiation of the energy of a contact explosion is an extremely difficult one. It is characterized by the fact that it takes place at the interface of two media: air and a solid half-space. However, the problem can be solved experimentally in a relatively simple fashion. V. D. Alekseenko [22] analysed lots of experimental data and summarized them in Table 1, which indicate that the material of targets and also the position of the charge relative to the free surface have a significant effect on the distribution of the energy of a contact explosion.

Table 1The distribution of the energy of a contact explosion

Quantity | Explosion on concrete | Explosion on undisturbed sand | Explosion on loose sand | |||

Charge on surface | Charge on surface | Center of charge level with surface | Center of charge 1 radius below surface | Charge on surface | Center of charge level with surface | |

E1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.7 | 0.56 |

E2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.3 | 0.44 |

Note: E1, E2 are respectively the fractions of energy radiated into (pumped into) the air and the target | ||||||

Based on theoretical analyses, O. V. Nagornov and V. E. Chizhov [23] found the energy fraction of a contact explosion:

where ρ01, γ1 are respectively the density and the adiabatic index of the upper medium (air), while ρ02, γ2 are respectively the density and the isentropic adiabatic index of the lower solid materials. However, for materials with γ> 3, this formula is not applicable.

Generally, it is possible to obtain the fractions of energy radiated into (pumped into) the concrete target which is subjected to a contact explosion.

Therefore, it is possible to calculate the local damage effect of the target subjected to a contact explosion.

2.2. Basic theoretical methods

Based on the conversation of energy, internal energy, which is dissipated in the concrete matches the external work done, as is supplied by the explosion. Material yields and fractures, pieces rub and slide against each other, which dissipates energy. The deformation and displacement in the plastic stage are much greater than those in the elastic stage, therefore it is reasonable to ignore the energy dissipated in the elastic stage. In the area near the explosion source, material undergoes large irreversible deformation, which in addition to the presence of the free surface, means that the elastic displacement can be ignored [24]. Therefore, it is acceptable to use a rigid-plastic model to describe the dynamic behaviour of concrete in such cases.

According to the conservation of mass, the incompressibility of the material, and the applied boundary conditions, it is possible to build a permissible kinematic velocity field which can characterise the deformation and displacement in the plastic zone. Combined with extremum principles and energy equilibrium rules [24], it is possible to deduce an expression for material resistance to explosive load on slabs with different thicknesses. Based on the non-dimensional expressions of material resistance, curves of material resistance may be plotted to find the threshold radius of the crushed zone which leads to spalling or punching. Combined with the initial conditions, the final crushed zone radius can be calculated by integrating the equations of motion for the expansion process.

It can be supposed that the material resistance is P, so the equations of motion can be written as:

where M is the mass of the initial expansion body, and R is the radius of the crush zone. Combined with the initial conditions of the expansion body:

The final radius of crush zone can be calculated, similarly, the two kinds of threshold radius of crush zone can be obtained. It is possible to predict what kind of damage effects will occur in certain thicknesses by comparing the final radius and the two threshold radii.

The material resistance can be acquired by seeking the limiting load. When the load reaches the limit for an ideal plastic-rigid body (with a yield plateau), free plastic flow occurs. According to extremum principles and energy equilibrium requirements, the rate of work could be written as follows [24, 25]:

where S and V respectively are the areas and the volumes of the deformed body, Pki are components of surface forces, vi are components of the possible kinematic velocity fields, ξkij=12(∂υki∂xj+∂υkj∂xi) are components of strain rates, σkij are components of the actual stress, Sτ are surfaces of velocity discontinuity, τs is the shear yield strength of material, and [vkτ] denote the jump vkτ+-vkτ- on Sτ.

By virtue of the Saint Venant-von Mises equation, we know that vectors σkij and ξkij will be parallel and the quantity σkijξkij, being the scalar product of two parallel vectors, will be equal to the product of their moduli, i.e. σkijξkij=τSHk, where τS is the yield limit for shear, Hk is the intensity of shear strain-rate. Then Eq. (7) can be written as:

According to Eq. (8), the upper bound for the limit load of Pki could be calculated from the permissible kinematic velocity field. Therefore, the problem becomes one of how to establish an accurate kinematic velocity field from the experimental data.

3. The limiting load: material resistance

3.1. Material resistance of thick slabs under point-source explosion load

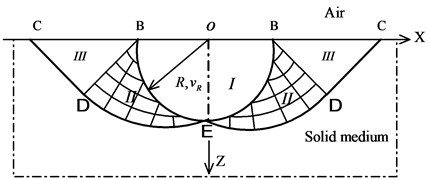

When the slab is sufficiently thick, compression craters are likely to be generated on the front-face while no deformation is supposed to occur on the back-face under the applied contact explosion load. This can be regarded as a point-source explosion on the surface of the half-space medium. In this paper, a rigid-plastic model is used to describe the crushing mechanism as a shear failure as dictated by Eq. (7). According to experimental observations and slip line field theory [25], a kinematically admissible velocity field (Fig. 4) can be established and the medium can be divided into three regions.

As shown in Fig. 4, the zone (FGF) nearest the explosion source is an initial expansion body with radius a and average radial velocity v0. The medium in region I is in a state of plastic flow. By combining the initial conditions, and according to mass conservation and the incompressibility of the material, vR=a2/R2v0 and vφ=vθ=0 can be acquired. According to the given velocity field, we can deduce the strain rate field and the strain rate is computed as H1=2√3a2v0/R3.

Fig. 4A kinematically admissible velocity field for thick slab

The kinematically admissible velocity fields in regions II and III can be calculated according to plasticity theory. The plasticity theory proposed by Hill [25] presents solutions to plane problems, and can describe the horizontally cylindrical charge effect on the surface of a material. According to symmetry, the velocity slip line field of the plane problem is rotated along the Z-axis to obtain the kinematically admissible velocity field under the action of a point-source explosion. As the rigid-plastic model complies with the associated flow rule, the strain slip line is overlapped with the velocity slip line so that the slip line in the model is not only the trajectory of the medium but also the direction of the shear stress (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5The velocity fields in regions II and III

Given that the curve BEB is the collision contact surface, and the change of its radius shows geometrical similarity with the expansion process, and as there are no shear stresses on BE, the slip line forms an angle of 45° with the surface. All β are straight lines and the tangent to the virtual circle with centre of O and radius R/√2 are developed: α is the involute of this virtual circle. In region I, the expanding speed of the radius R of the crushed zone is vR=a2/R2v0. Then the velocity along line α on BE is vα=√2vR, while those on lines α and β in region BDE are vα=√2vR and vβ=0 separately. Thus, it can be known that region BCD moves along DC at a speed of vα=√2vR.

Exploiting symmetry, the right-hand part of the slip line field is acquired (Fig. 6). The radius of the virtual circle is r=R/√2 and it is the involute of the cluster line α; DE and BD are the outer boundaries of region BDE, and belong to clusters α and β, respectively. If the expressions for curves DE and BD are known, we can calculate the volume of the region BDE after it is rotated around the Z-axis and the surface area corresponding to DE.

The curve ED is the involute of the virtual circle presented in Fig. 6. By randomly selecting a point M(x,y) on the curve to make MF tangential to the circle at F, then ∠xOF=φ, OF=r and KF=MF. The parametric expression of curve ED can be acquired according to the geometric relationships:

Fig. 6The schematic boundary lines of plastic regions II and III

By drawing a tangent line EN to the virtual circle at point E and letting OE=R and ON=R/√2, then EN=R/√2 and ∠EON=π/4 can be acquired. Moreover, ^KN=EN=R/√2, therefore φ= 1 and γ=1-π/4. The deflection angle between the Z-X plane and the x-y plane is γ=1-π/4. Similarly, BD=rπ/2. In the Z-X plane, let OM be the radius ρ in polar coordinates and ∠ZOM be the deflection angle φ measured from the Z-axis, then:

Given that the rate of cavity expansion along the line α is u=√2vR (vα=√2vR), the velocity component in the polar coordinate can be obtained as follows:

By rotating the plastic zone around the Z-axis, we express the plastic zone in spherical coordinates with rotation angle θ. The velocity fields in all regions, in spherical coordinates (ρ,φ,θ), can then be obtained.

For the kinematically admissible velocity field in region II: vIIρ=vα/√1+ϕ2,vIIφ=ϕvα/√1+ϕ2 and v2θ=0; as to the strain rate field: ξIIρ=-vα/r(1+ϕ2),ξIIθ=vα/r(1+ϕ2) and ξIIϕ=vρ/ρ+∂vϕ/ρ∂ϕ=vα/r(1+ϕ2)+vα/r(1+ϕ2)1/2ϕ2; the shear strain rate is HII=vα√2(3ϕ4+2ϕ2(1+ϕ2)1/2+1+ϕ2)/rϕ2(1+ϕ2). The velocity difference on the surface of the tangential velocity discontinuity in region II is constant at |[vIIτ]|=√2vα. The surface area of the velocity discontinuity is SII=8.956πr2. The rectangular form of the velocity field in region III can be expressed as vIIIZ=-vR, vIIIX=vR and vIIIθ=0. The strain rate field and the shear strain rate can be represented by ξIIIZ=ξIIIX=ξIIIθ=0 and HIII=0. The velocity difference on the surface of the tangential velocity discontinuity in region III is constant at |[vIIIτ]|=√2vα. The surface area of the velocity discontinuity is SIII=1.745πr2.

By substituting the physical quantities obtained above into Eq. (8), the material resistance on the surface of the half-space medium under application of a point-source explosion can be expressed in non-dimensional form as follows:

3.2. Calculation of the resistance of the limited-thickness slab subjected to point-source explosion

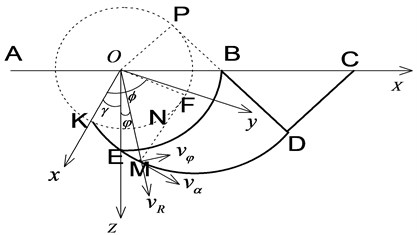

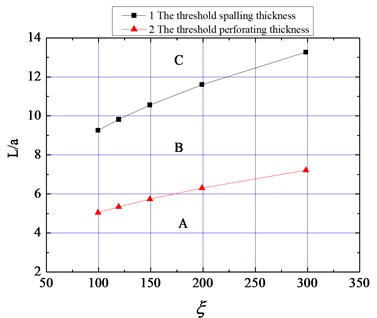

When a point-source explosion occurs on the surface of a limited-thickness slab, the back face of the target is affected. When the radius R of the crushed zone reaches a certain value, the target material begins to be moved outwards from the back face instead of the front-face when it is subjected to contact explosion loading. Fig. 7 shows the regional division of a limited-thickness slab subjected to a point-source explosion. Region I is the crushed zone around the explosion source, while region II is the fracture zone caused by reflected tensile waves on the back face. Region III is the elastic deformation area in which deformation and displacement can be neglected.

Under such circumstances, the medium in region I flows towards region II. Considering the hindering effect of the medium in region II on the expansion body (the medium within AOA), region ACCA is considered as an expansion body with an initial velocity vR and the radius of the impact contact line AA is R. Here, shear yield is supposed to occur to the material so that line AB (the regional discontinuity) forms an angle of π/4 with the back face. There are two kinematically admissible velocity fields in region II: in the first, the velocity components in all directions change with position and therefore the medium is plastically deformed while in the second velocity field, the velocity components in all directions are position-independent and the medium moves as a rigid block.

Fig. 7The regional division of a limited-thickness slab subjected to point-source explosion

3.2.1. The first kinematically admissible velocity field

Region II in Fig. 7 lies within:

while the shell in the crushed zone lies in:

The volume and area of the cone in ∑1 are V1=2πa3(1-cosφ0)/3 and S1=2πa2(1-cosφ0), separately. Similarly, we can calculate the volume and area of the cone in ∑2 as V2=2πR3(1-cosφ0)/3 and S2=2πR2(1-cosφ0).

(1) According to mass conservation, suppose that vr denotes the radial velocity and S2⋅vr|r=R=Sr⋅vr where vr|r=R=vR represents the average motion velocity of the fracture shell, then vr=R2vR/r2. Based on the incompressibility of the material and the regional symmetry, ∂vr∂r+2vrr+∂vϕr∂ϕ+∂vθr∂θ=0 and vθ=0. By substituting vr=R2vR/r2 into this equation, -2R2r3vR+2R2r3vR+∂vφr∂φ=0 and therefore, vϕ=const. According to the continuity condition vn=0 of the normal velocity on the conical surface, vϕ=0.

(2) When the velocity field is known, the strain rate field is given by: ξr=∂vr∂r=-2R2r3vR, ξθ=ξϕ=vrr=R2r3vR.

(3) The strain rate is expressed as H=√2(ξ2r+ξ2θ+ξ2ϕ)=2√3R2r3vR.

(4) According to the upper bound on the limiting load:

the limit load of the material resistance can be obtained:

3.2.2. The second kinematically admissible velocity field

The second kinematically admissible velocity field only changes with time, shown in Fig. 8. The media, in different positions, have the same velocity, which suggests that rigid blocks are directly forced out from the funnel region by the expansion body. Initially, the rigid blocks have different velocities to the expansion body. While with continuing motion, the rigid blocks tend to match the velocity of the expansion body. This process is so short as to be negligible. Therefore, the initial velocity of rigid blocks is regarded as equal to that of the expansion body. The medium is mainly affected by the frictional force on the surface of each discontinuity.

Fig. 8The regional division of a thin slab subjected to point-source explosion

As the velocity component in the region II is vr=vR, vφ=0, vφ=0, then Hk=0 and |[vkτ]|=vR. The surface discontinuity forms a part of the conical surface: S=√2π(L2-R2). By substituting these parameters into ∫SPknividS=τs∫VHkdV+∑Nk=1τs∫Sk|vkτ|dSk, an equation similar to Eq. (13) is obtained as follows:

4. Theoretical computation of the threshold thickness of a slab

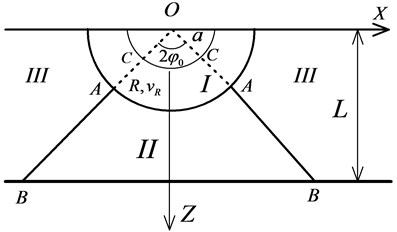

4.1. Non-dimensional of explosion resistance

By non-dimensional Eqs. (12), (13), and (14), the resistance to a point-source explosion on the surface of the half-space is obtained, as follows, by using the given radius a of the charge and ˜L=L/a:

The resistance of a slab with limited thickness to a point-source explosion in the first velocity field is expressed as:

The resistance of a limited-thickness slab to a point-source explosion in the second velocity field is:

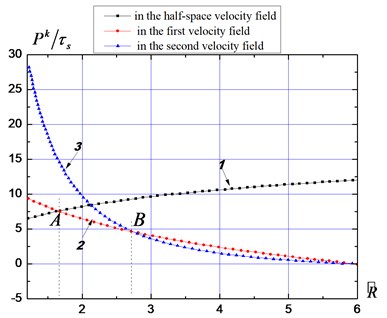

Fig. 9Material resistance curves

a) Perforation before spalling

b) Explosive punching

By regarding Pk/τs as a function related to ˜R, the Pk/τs-˜R curves in the three velocity fields can be calculated. Suppose that the slabs are L=6a and L=1.5a thick, as shown in Fig. 9(a) and 9(b) separately: curves 1, 2, and 3 represent the impact resistances in the half-space velocity field as well as the first and second velocity fields of the medium with limited thickness, respectively. Curves 1 and 2 intersect at point A, showing that when the radius of the fracture zone extends to ˜RA, free surfaces are formed by the expansion body; curves 2 and 3 intersect at point B, meaning that when the radius of the fracture zone extends to ˜RB, the upper media are forced out from the ground surface by the expansion body and plugging occurs. For each ˜R value, three impact resistance values can be found. Thereinto, the minimum values are selected as the actual resistances, namely, the values from curves 1 and 2 to the left and right of point A, respectively.

In the explosion, the sum of the material resistance to the surrounding plastic zone subjected to impact on the contact surface is expressed as follows:

where, Sr is the area of the impact contact surface. In the half-space, it can be regarded as Sr=2πr2 without considering the influence of the free surfaces. While in a limited thickness slab, Sr=2πr2(1-cosφ0), φ0=π/4.

4.2. Method of calculating the threshold thickness on spalling

Based on the impact resistance curves, the limiting material resistance can be calculated. By combining the initial conditions to solve the equation of motion, the radius of the crushed zone can be computed. In fact, the wave problem is converted to, and solved as, the resistance. Under threshold spalling conditions, the explosion resistance is P1=pk2πa3˜R2 and the mass M1=M=23πρa3 of the initial expansion body is a constant. By combining Eqs. (5), (15), and (18), the non-dimensional equation of motion can be obtained as follows:

The initial conditions are:

Let ω1=6.92πτsa/M1 and ω2=11.68πτsa/M1, the equation of motion is converted to:

As this differential equation, cannot be solved directly, the equation needs to be converted to -˜vd˜vd˜R=ω1ln(˜R)˜R2+ω2˜R2 form and then, separating the variables and integrating gives:

Processing Eq. (22), we obtain:

Let ξ=4.5ω1(v0a)2=0.65M1v20πτsa3, then solving Eq. (23) gives:

The thickness of the medium at intersection point A can be calculated by using Eqs. (15) and (16):

By substituting Eq. (24) into (25), the threshold spalling thickness can be acquired:

Eq. (26) is a function of the non-dimensional factor ξ. According to Eq. (2), the relationship between the non-dimensional factor ξ and the mass Q of the charge can be obtained:

According to the physical model of a contact explosion (Fig. 3), Rw=a can be obtained so that ξ=1.73ηQvδρw/τs. By performing dimensional analysis, ξ=λ(ρwρ)(σdτs)(QvδCpvm). As a non-dimensional combination of the polytropic index, it represents the internal relationship between the density of the charge, explosion heat, effective energy ratio, the mechanical equivalent of heat, the density of the material, its shear yield strength, peak pressure sustained, deformation wave velocity, and maximum particle velocity.

There are LambertW functions, recorded as W(x), in Eqs. (24) and (26). When the variable x>-e-1, W(x) is an increasing function with real, unique solutions. Therefore, the solutions of all the functions in this paper are real, single-value, numbers.

By converting the threshold spalling thickness in its non-dimensional form to its scaled distance form, it is found that:

Under the condition in which the parameters of the charge and media are determined, the non-dimensional factor ξ is also determined. By combining Eq. (26), this scaled distance can be calculated. When the model size is changed, it is a similar constant that serves as a basis for determining whether, or not, spalling occurs. For small-scale underground chemical explosions where the gravitational acceleration can be ignored, this result corresponds to the similarity law governing explosions.

4.3. Method of calculating the threshold thickness on perforating

To calculate the threshold perforating thickness, it is necessary to obtain the displacement and velocity of point A from the impact resistance curves. At this time, owing to the appearance of the back surfaces (free surfaces) when affected by the expansion body, the perforation body begins to be formed. The material resistance in the equation of motion is calculated using the first velocity field in the medium with its limited thickness. When the radius of the crushed zone develops to reach point B, perforation occurs. According to the relationship between the radius of the crushed zone at point B and the slab thickness, the threshold perforating thickness can be calculated.

According to the mechanical model for explosive perforation, the explosion resistance and mass of the expansion body can be obtained as P2=pk2πa2˜R2(1-cosφ0) and M2=2πρa3(1-cosφ0)/3, respectively. By combining Eqs. (5), (16), and (18), the equation of motion when the perforation body begins to be formed can be acquired:

The initial condition is:

and the threshold perforating condition is:

Let ω3=17.63τs/ρa2, the equation of motion may be converted to the following form: ¨˜R=-ω3ln(˜L˜R)˜R2. By separating the variables and then integrating -˜vd˜vd˜R=ω3ln(˜L˜R)˜R2, from the initial state to the threshold perforating state, we get:

Based on Eq. (22), we can obtain the relationship between the velocity and displacement under the initial conditions at which perforation begins to occur:

By combining Eqs. (30) and (31), the following formulae can be acquired by removing the term in vA:

According to the aforementioned definitions of ω1, ω2, ω3:

We can obtain:

Based on Eq. (25), the relationship between the radius of the crushed zone and the slab thickness at point A (in its initial state) may be found to be:

In addition, according to Eqs. (16) and (17), the relationship between the radius of the crushed zone and the slab thickness at point B at the threshold perforating state can be acquired:

By combining Eqs. (32) to (35), an equation relating ˜L with minimus quantities being ignored can be acquired by sorting the equation of motion of that perforation formed by the explosive expansion body on the back-face of the slab and the initial and boundary conditions:

In Eq. (36), ξ represents the non-dimensional impact factor and has an identical meaning to that used in the calculation of the threshold spalling thickness. The root of this equation is the threshold perforating thickness that can simultaneously satisfy the equation of motion for perforation, the initial conditions, and boundary conditions. However, as analytical solutions cannot be obtained, we calculate an approximate solution using a numerical method. By combining Eqs. (28) and (36), the relationship between the threshold spalling thickness and the non-dimensional impact factor ξ (in scaled distance form) can be acquired.

5. Analysis of typical examples

5.1. Theoretical analysis of two kinds of threshold thicknesses

Suppose that the shear yield strength of concrete slabs ranges from 2 MPa to 6 MPa; the density of the TNT charge is ρw= 1630 kg/m3; the heat liberated in the explosion is Qv=1010 kcal/kg; the mechanical equivalent of heat is δ=4187 J/kcal. According to Table 1, the fraction energy radiated into the slabs is 0.1, i.e.η≈ 0.1.

Table 2The calculated data of threshold thickness of spalling and perforating

Shear yield strength (MPa) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

Non-dimensional impact factor | 298.478 | 198.985 | 149.239 | 119.391 | 99.493 | |

Threshold thickness | Spalling (1) | 13.263 | 11.606 | 10.562 | 9.821 | 9.257 |

Spalling (m/kg1/3) | 0.699 | 0.612 | 0.557 | 0.518 | 0.488 | |

Perforating (1) | 7.208 | 6.307 | 5.740 | 5.337 | 5.031 | |

Perforating (m/kg1/3) | 0.380 | 0.332 | 0.303 | 0.281 | 0.265 | |

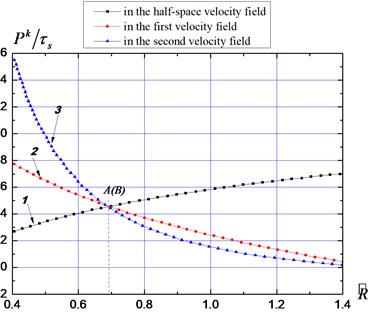

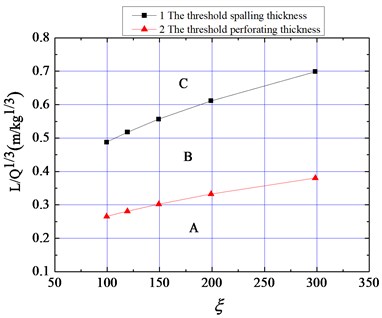

By combining Eqs. (26), (27), (28), and (29), the threshold thickness of spalling and perforating have been calculated and listed into Table 2. Besides, the plot of ˜L~ξ in non-dimensional form, and that of L/Q1/3~ξ in scaled distance form can be acquired as shown in Fig. 10(a) and 10(b), respectively.

Fig. 10The relationship between threshold thickness and non-dimensional impact fact

a) The threshold thickness in non-dimensional form

b) The threshold thickness in scaled distance form

As shown in Fig. 10, the threshold spalling thickness and the threshold perforating thickness increase with increasing non-dimensional impact factor ξ. The larger the value of ξ, the larger the threshold thicknesses, and vice versa. The non-dimensional impact factor is a comprehensive index covering the density of the charge, the heat liberated by the explosion, the effective energy ratio, and the shear yield strength of the material. It is proportional to the impact load or energy transmitted from the explosion source to the medium, but is inversely related to the strength, or resistance, of the medium. The higher the impact load applied by the explosion, the thicker the material must be to resist impact; the higher the strength of the material, the greater the explosion-resistance of the material, the thinner it need be to resist the impact.

After calculation, it can be found that the threshold spalling thickness Lz is about twice the threshold perforating thickness LP, which agrees with the relationship Lz=2LP as shown in the BRL formula and the revised version thereof.

5.2. Numerical analysis of two kinds of threshold thicknesses

5.2.1. Numerical model

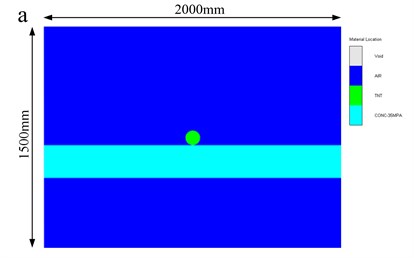

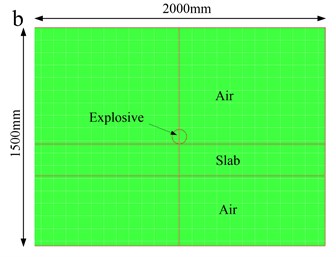

In order to verify the accuracy of theoretical results, the numerical analysis was performed with the hydrocode AUTODYN v12.0 [27]available from ANSYS. In the numerical simulation, the concrete slabs subjected to contact explosions are modelled with an axial symmetric two-dimensional model with an element size of 5 mm [28], as shown in Fig. 11. The slab is modelled by a Lagrange subgrid, in which the coordinates move with the material. In order to describe the infinite boundary of slab, the lateral Lagrange subgrid is set as a non-reflecting boundary, which eliminates the reflections of wave from the boundary. On the other hand, the air and high explosive are modelled by the Euler subgrid, wherein the grid is fixed, with material allowed to flow through [29, 30]. The Euler-Lagrange interface interaction is considered, which means that the Lagrange subgrid imposes a geometric constraint on the Euler subgrid whereas the Euler subgrid provides a pressure boundary to the Lagrange subgrid [31]. The boundary condition of the Euler subgrid is set as an outflow boundary. The erosion technique is adopted to simulate the damage process.

Fig. 11Numerical model: a) different materials in the model; and b) numerical mesh.

Combined with Table 2, the theoretical results of threshold thickness of slab under contact explosions have been calculated and shown in Table 3, in which the shear yield strength of material is 6 MPa and the mass of charge is 0.853 kg.

Table 3Threshold thickness by theoretical calculation

Shear yield strength of material (MPa) | 6 |

Radius of charge (mm) | 50 |

Mass of charge (kg) | 0.853 |

Threshold spalling thickness (m) | 0.416 |

Threshold perforating thickness (m) | 0.226 |

In numerical models, the charge of explosives and material properties of slab are set according to Table 3, which are both constant for all models. But the thickness of slab is different in each model, which varies from 120 mm to 520 mm. More detailed properties for numerical model have been listed in Table 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Table 4Numerical model

Slabs |

Material: concrete Shear yield strength: 6 MPa Thickness: 120 mm, 220 mm, 320 mm, 420 mm, 520 mm Subgrid: Lagrange |

Charge of explosives |

High explosive: TNT Density: 1630 kg/m3 Radius: 50 mm Mass: 0.853 kg Subgrid: Euler |

5.2.2. Air

The ideal gas equation of state was used for the air. It follows that the equation of state for a gas, which has uniform initial conditions, may be written as [32, 33]:

where p is the hydrostatic pressure, ρ is the density and e is the specific internal energy.

Table 5Material properties for Air

EOS: Ideal gas |

Adiabatic index: γ0=1.4 Reference density: ρ0=0.001225 g/cm3 Reference temperature: T0=288.2 K Specific heat: cv=717.3 J/kg |

5.2.3. TNT

The Jones-Wilkins-Lee EOS, which represents the pressure generated by chemical energy in an explosion and can be written as [27, 32]:

where P is the hydrostatic pressure; V is the specific volume; e is the specific internal energy; and A, B, R1, R2, and ω are material constants.

Table 6Material properties for TNT [28, 31]

EOS: JWL |

Reference density ρ0= 1.63 g/(cm3); A= 3.7377E8 kPa; B= 3.73471E6 kPa R1= 4.15; R2= 0.9; ω= 0.35 C-J detonation velocity: 6.93E3 m/s C-J energy/unit volume: 6E6 KJ/m3 C-J pressure: 2.1E7 kPa |

5.2.4. Material model for concrete

In the present work [33], the Riedel, Hiermaier, and Thoma (RHT) dynamic damage model for concrete is adopted. This model is particularly useful for modelling the dynamic response of concrete. The material constants adopted in the present work are based on the typical data for concrete.

Table 7Material properties for concrete [28, 33, 34]

EOS: P alpha |

Porous density: ρ0= 2.314 g/(cm3) Porous sound speed: 2.920E3 m/s Initial compaction pressure: 2.330E4 kPa Solid compaction pressure: 6.000E6 kPa Compaction exponent: 3.0 Bulk modulus: 3.527E7 kPa |

Strength: RHT Concrete |

Shear Modulus: 1.670E7 kPa Compressive Strength: 3.5E4 kPa Tensile Strength: 3.5E3 kPa Shear Strength: 6E3 kPa Intact Failure Surface Constant A: 1.6 Intact Failure Surface Exponent N: 0.61 |

Failure: RHT Concrete |

Damage Constant, D1: 0.04 Damage Constant, D2: 1.0 Minimum Strain to Failure: 0.01 Fracture Energy, Gf: 70.000 J/m2 |

5.2.5. Results and discussion

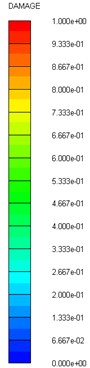

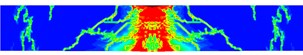

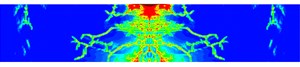

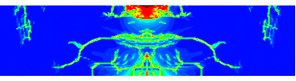

There are a series of numerical models have been built, and the numerical results of damage contour are shown in Table 8.

The numerical results (in Table 8) show that as the thickness increases, the damage of the slab decreases, which is reasonable and consistent with common sense. Due to the thicker slab can stand higher loads, under the same blast loads, the lighter damage will occurs. In order to discuss the degree of damage, it is essential to define some categories of damage. Even though there are lots of experimental and numerical study on damage of slabs subjected to blast loads, the available literature does not provide a definition for the damage criterion under which the spallation or perforation failure occurs. Besides, most of the literatures [35, 36] are concerned on the spall damage and fracture of ductile and brittle metals, which are less about the construction materials such as concrete and rock [37, 38].

Lu Fangyun et al. [34] divided the damage of one-way square slabs into the following categories: (a) low damage, with only small cracks in both surface of the slab; (b) moderate damage, with spallation occurring on bottom of the slab; (c) high damage, with perforation from the upper to the bottom surface; and (d) collapse damage, which is the punching failure of the slab. Due to their works focus on the structural holistic performance of slabs subjected to standoff blast loads, they defined damage criteria correlated to the displacement or the support rotation angle. However, these categories cannot be applied to judge the local damage effects of slabs under contact explosions, which are much different from the former.

According to McVay M. K. [39], the spall damage of concrete slabs can be divided into three categories: (I) Light damage: from initial state to a few barely visible cracks; (II) Threshold for spall: from a few cracks and a hollow sound to a large bulge in the concrete with a few small pieces of spall on the bottom surface, which is equivalent to threshold spallation in this paper; and (III) Medium spall: from a very shallow spall to spall penetration up to one third of the slab thickness. But he did not define the more serious damage, which was perforation or punching. Therefore, it is essential to add two damage categories: (IV) Threshold for perforation: from a spall to perforate the slab, which means the spall crater connects to the blast crater; (V) Perforation or punching: blast crater on the top of slab extends to the bottom, which means a big hole occurs on the slab.

Therefore, combined with the damage contour of numerical results, it is possible to classify the damage degree of each target under the same blast load (0.853 kg TNT) according to categories of spall damage of concrete slabs, which has been listed in Table 8.

As shown in Table 8, the colour scale describes the degree of damage, where red represents the most serious damage. The thickness of No. 2 and No. 4 targets are respectively threshold perforating thickness and threshold spalling thickness of slab under contact explosion (0.853 kg TNT), which are very close to the theoretical calculation by this paper, shown in Table 3. To an extent, it can proved that the method of this paper to calculate the local damage of slabs subjected to a contact explosion is reasonable.

Table 8Damage of numerical results

Targets | Thickness (mm) | Damage contour | Local damage on the bottom | Categories | |

No. 1 | 120 |  |  | Blast crater extends to the bottom of the target | Perforation |

No. 2 | 220 |  | Damaged area just connected to the blast crater | Threshold perforation | |

No. 3 | 320 |  | Damage or failure up to one third of the slab thickness | Spallation | |

No. 4 | 420 |  | A few small pieces of spall | Threshold spallation | |

No. 5 | 520 |  | A few barely visible cracks | Light damage | |

6. Conclusions

This research converted the contact explosion on the medium surface to a collision of an initial expansion body with the medium under consideration. By using the extremum principle, this study derived the explosion resistance. In addition, by combining the equation of motion, and solving for the initial conditions and boundary conditions, this research deduced the threshold spalling thickness and the threshold perforating thickness. Moreover, the following conclusions were obtained:

1) The threshold thicknesses were determined by use of non-dimensional impact factor ξ and they were in an approximately linear relationship to each other. The non-dimensional impact factor ξ reflected the effects of the energy efficiency of the explosives and the material strength. It denoted the explosive effect on the material. The larger the heat liberated by the explosion, the larger the density and specific energy coefficient of the explosive (all of which illustrated the higher the efficiency of the explosive, the smaller the calculated ξ) and the larger the threshold thickness; the higher the yield strength of the medium, which indicated that the weaker the explosion, the stronger the resistance of the medium thereto.

2) This research quantified the relationship between the threshold thickness and the non-dimensional impact factor ξ in the plane ˜L~ξ or L/Q1/3~ξ. The threshold spalling thickness was about twice that of the threshold perforating thickness under the same impact factor ξ. This conclusion was consistent with that obtained using the BRL formula and the revised version thereof.

3) Compared with the results of numerical simulation, the proposed calculation method was shown to be reasonable. The method revealed the physical essence of the empirical formula on calculating threshold thickness of slabs subjected to contact explosions.

References

-

Li J., Hao H. Numerical study of concrete spall damage to blast loads. International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 68, 2014, p. 41-55.

-

Qian Q. H., Wang M. Y. Calculation Theory for Advanced Protective Structures. Phoenix Science Press, Nanjing, 2009.

-

Zheng Q. P., Zhou Z. S., Qian Q. H., Hu J. H. Spalling in protective structures. Chinese Journal of Rock Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 22, Issue 8, 2003, p. 1393-1398.

-

Barbee T. W., Seaman L., Crewdson R., Curran D. R. Dynamic fracture criteria for ductile and brittle metals. Journal of Materials, Vol. 7, Issue 3, 1972, p. 393-401.

-

Rinehart J. S. Stress Transients in Solids Hyperdynamics. Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1975.

-

Barber R. B. Steel Rod/Concrete Slab Impact Test (Experimental Simulation). Bechtel Corporation, 1973.

-

Nikiforov B. C., Shemiyaki E. I. Solid Dynamic Fracture. Science, Russia, 1979.

-

Haldar A., Miller F. J. Penetration depth in concrete for nondeformable missiles. Nuclear Engineering and Design, Vol. 71, 1982, p. 79-88.

-

Hughes G. Hard missile impact on reinforced concrete. Nuclear Engineering and Design, Vol. 77, 1984, p. 23-35.

-

Li Q. M., Chen X. W. Dimensionless formulae for penetration depth of concrete target impacted by a non-deformable projectile. International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 28, 2003, p. 93-116.

-

Chen X. W., Li Q. M. Deep penetration of a non-deformable projectile with different geometrical characteristics. International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 27, 2002, p. 619-637.

-

Drake J. L. Protective Construction Design Manual. ESL-TR-87-57. Air Force Engineering and Services, Tyndall Air Force Base, 1989.

-

Wierzbicki T., Nurick G. N. Large deformation of thin plates under localised impulsive loading. International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 18, Issue 7, 1996, p. 899-918.

-

Luccionia B. M., Luege M. Concrete pavement slab under blast loads. International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 32, 2006, p. 1248-1266.

-

Wang M. Y., Qian Q. H., Zhao Y. T. The design method for shelter plate of steel plate and steel fiber reinforced concrete under contact detonation. Explosion and Shock Waves, Vol. 22, Issue 2, 2002, p. 163-168.

-

Zhang X. B., Yang X. M., Chen Z. Y., Deng G. Q. Explosion spalling of reinforced concrete slabs with contact detonations. Journal of Tsinghua University (Science and Technology), Vol. 46, Issue 6, 2006, p. 765-768.

-

Wang G. H., Zhang S. R. Damage prediction of concrete gravity dams subjected to underwater explosion shock loading. Engineering Failure Analysis, Vol. 39, 2014, p. 72-91.

-

Tan Z., Zhang·W., Cho·C., Han X. Failure mechanisms of concrete slab-soil double-layer structure subjected to underground explosion. Shock Waves Vol. 24, 2014, p. 545-551.

-

Li J., Wu C. Q., Hao H. An experimental and numerical study of reinforced ultra-high performance concrete slabs under blast loads. Materials and Design, Vol. 82, 2015, p. 64-76.

-

Zheng Q. P., Qian Q. H., Zhou Z. S., Hu J. H., Xu J. X. Comparative analysis of scabbing thickness estimation of reinforced concrete structures. Engineering Mechanics, Vol. 20, Issue 3, 2003, p. 47-53.

-

Henrych J. The Dynamics of Explosion and Its Use. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, 1979.

-

Alekseenko V. D. Experimental investigation of the energy distribution in a contact explosion. Translated from Fiziko-Tekhnicheskie Problemy Razrabotki Poleznykh Iskopaemykh (Combustion, Explosion and Shock Waves), Vol. 3, Issue 1, 1967, p. 152-155.

-

Nagornov O. V., Chizhov V. E. Energetic estimate of the action of a contact explosion. Moscow Engineering Physics Institute, translated from Fiziko-Tekhnicheskie Problemy Razrabotki Poleznykh Iskopaemykh (Combustion, Explosion and Shock Waves), Vol. 4, 1989, p. 57-60.

-

Kasyanov L. M. Plasticity Theory Foundation. North-Holland Amsterdam, 1971.

-

Hill R. The Mathematical Theory of Plasticity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1950.

-

Borvik T., Hanssen A. G., Langseth M., Olovsson L. Response of structures to planar blast loads – a finite element engineering approach. Computers and Structures, Vol. 87, 2009, p. 507-520.

-

AUTODYN. Theory Manual. Century Dynamics, 2006.

-

Abdullah R., Mokhatar S. N. Computational analysis of reinforced concrete slabs subjected to impact loads. International Journal of Integrated Engineering, Vol. 4, Issue 2, 2012, p. 70-76.

-

Chen L., Graybeal B. A. Finite element modelling of ultra-high-performance concrete bridge girders. Transportation Research Board 90th Annual Meeting, No. 11-1015, 2011.

-

Trivedi N., Singh R. K. Prediction of impact induced failure modes in reinforced concrete slabs through nonlinear transient dynamic finite element simulation. Annals of Nuclear Energy, Vol. 56, 2013, p. 109-121.

-

Ambrosini R. D., Luccioni B. M., Danesi R. F., Riera J. D., Rocha M. M. Size of craters produced by explosive charges on or above the ground surface. Shock Waves, Vol. 12, 2002, p. 69-78.

-

Luccioni B., Ambrosini D., Nurick G., Snyman I. Craters produced by underground explosions. Computers and Structures, Vol. 87, 2009, p. 1366-1373.

-

Tu Z. G., Lu Y. Evaluation of typical concrete material models used in hydrocodes for high dynamic response simulations. International of Journal Impact Engineering, Vol. 36, issue 1, 2009, p.132–146.

-

Wang W., Zhang D., Lu F. Y., Wang S. C., Tang F. J. Experimental study and numerical simulation of the damage mode of a square reinforced concrete slab under close-in explosion. Engineering Failure Analysis, Vol. 27, 2013, p. 41-51.

-

Hu L. L., Miller P., Wang J. L. High strain-rate spallation and fracture of tungsten by laser-induced stress waves. Materials Science and Engineering A, Vol. 504, 2009, p. 73-80.

-

Kanel G. I., Sugak S. G., Fortov V. E. Models of Spall Fracture. Institute of Chemical Physics, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Chernogolovka, translated from Problemy Prochnosti, Vol. 8, 1983, p. 40-44.

-

Nash P. T., Vallabhan C. V. G., Knight T. C. Spall damage to concrete walls from close in cased and uncased explosions in air. ACI Structure Journal, Vol. 92, Issue 6, 1995, p. 680-688.

-

Zhou X. Q., Hao H., Deeks A. J. Modeling dynamic damage of concrete slab under blast loading. Proceeding of the 6th Asia-Pacific Conference on Shock and Impact Loads on Structures, Perth, WA, Australia, 2005, p. 703-710.

-

Mcvay M. K. Spall Damage of Concrete Structures. Technical Report SL 88-22, US Army Corps of Engineers Waterways Experiment Station, 1988.

Cited by

About this article

This work was supported by the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Teams in Universities of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. IRT13071) and the National Natural Science Foundation for the Youth of China (Grant Nos. 51308543, 51308542 and 51409257).

Professor Mingyang Wang has made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; and Doctor Songlin Yue has drafted the work and made contributions to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; and Associate Professor Yangyu Qiu has revised it critically for important intellectual content; and Lecturer Ning Zhang has supplied editing and writing assistance.

The authors declare that there are no competing financial interests regarding the publication of this paper.