Abstract

The sensitivity of human hearth’s rhythm to the fluctuations of Earth’s local magnetic field is analyzed in this paper. Data collected during the long-term project of heart-rate variability (HRV) data from 17 female volunteers were used to correlate to measured fluctuations of Earth magnetic signals. Magnetic signals are collected utilizing the first global network of GPS time stamped detectors designed to continuously measure magnetic signals that occur in the same range as human physiological frequencies such as the brain and cardiovascular systems.

1. Introduction

Every cell in our body is immersed in an environment of both external and internal fluctuating magnetic fields that can affect virtually every cell and circuit in biological systems to a certain degree, depending on the specific biological system and the nature of the magnetic fields. Numerous studies have shown that various physiological rhythms and global collective behaviors can be synchronized with the solar and geomagnetic activity; and that disruptions in these fields may have adverse effects on human health and behavior [1, 2].

The natural variation in the geomagnetic field in and around Earth has been reportedly involved in relation to several human cardiovascular variables. These include blood pressure [3] heart rate (HR), and heart rate variability (HRV) [4, 5]. Although there exist mounting evidences for such effects, they are far from being fully understood. Several studies have found significant associations between magnetic storms and decreased heart rate variability (HRV), indicating a possible mechanism linking geomagnetic activity with increased incidents of coronary disease and myocardial infarction [6-8]. One study that analyzed week long recordings found a 25 % reduction in the VLF rhythm during magnetically disturbed days as compared to quite days. The LF rhythm was also significantly reduced but the HF rhythms were not [9, 10]. A comparison of frequency ranges of oscillations in biological systems and geomagnetic activity shows that oscillations in neurogenic and myogenic structures have which have the same frequency as geomagnetic oscillations have the highest sensitivity to the geomagnetic activity [11]. General nonspecific adaptive stress-response (increasing of heart rate (HR), reductions in heart rate variability (HRV) and increased number of arrhythmic events has been observed in the periods of magnetic storms [12]. It has been suggested that disruptions in environmental magnetic fields can act as a “stressor” that can trigger changes in brain electrical activity, in the same way as other known stressors [13].

The most likely mechanism for explaining how solar and geomagnetic influences affect human health and behavior are a coupling between the human nervous system and resonating geomagnetic frequencies called Schumann resonances that occur in the Earth-ionosphere resonant cavity, Alfven waves, and other very low frequency resonances. It is well established that these resonant frequencies directly overlap with those of the human brain, and the cardiovascular and autonomic nervous systems [14]. Those interactions are proposed influence cardiovascular health. Individual sensitivity and the specific dynamic effects to the influences of fluctuations and resonances in the earth’s magnetic field environment is the problem of particular importance, and developing methods to measure the sensitivity of individual’s susceptibility is needed. This study therefore examines the different types and levels of sensitivity to earth generated magnetic fields.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

From April 1, 2012, to August 31, 2012, a long-term project collected heart-rate variability (HRV) data from 17 female volunteers. All participants were employees of the Prince Sultan Cardiac Center in Hofuf Saudi Arabia (7 nursing staff, 6 housekeeping and, 4 from the research department). The average age was 32±8 years, ranging from 24-49 years. Two participants experienced uncomfortable irritation at the ECG electrode sites and dropped out of the study. The participants signed informed consent form before taking part in the study and were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

2.2. Data collection

All participants underwent weekly 24-72 hour ambulatory HRV recordings with Firstbeat Bodyguard HRV recorders; the Bodyguard HRV recorder calculates the Inter-Beat Interval (IBI) from the ECG measured at 1000 samples per second. IBI data is stored locally in the device memory and uploaded to the studies FTP data collection site at the end of each weekly recording period. Participant’s recordings were generally 72 hours in length and scheduled once a week over a 5 month period between April and the end of August 2012.

2.3. The registration of local magnetic field

The Global Coherence Initiative (GCI) system is the first global network of GPS time stamped detectors designed to continuously measure magnetic signals that occur in the same range as human physiological frequencies such as the brain and cardiovascular systems. Each site includes ultrasensitive magnetic field detectors (sensitivity 10-12 T) specifically designed to measure the magnetic resonances in the earth/ionosphere cavity, resonances that are generated by the vibrations of the earth’s geomagnetic field lines and ultra-low frequencies that occur in the earth’s magnetic field, all of which have been shown to impact human health, mental and emotional processes and behaviors. Each monitoring site detects the local alternating magnetic field strengths in 3 dimensions over a relatively wide frequency range (0.01-300 Hz) while maintaining a flat frequency response.

A technical problem prevented the first month’s data from being recorded. Beginning May 9th the time varying magnetic field was continuously monitored to the end of August at the local GCI monitoring site near Hofuf Saudi Arabia. Local magnetic field was calculated as the mean level of the magnetic field (picoTeslas (pT)) for every hour in the May 9th – Aug 31st monitoring period.

All HRV recordings were downloaded from the study’s data collection FTP site to a PC workstation and analyzed using DADiSP 2002. Inter-Beat Intervals greater or less than 30 % of the mean of the previous 4 intervals were considered artifact and removed from the analysis record. Following this automated editing procedure recordings were manually reviewed by an experienced technician and, if needed, corrected. Daily recordings were processed in consecutive 5 minute segments. Any 5 minute segment with >10 % of the IBIs either missing or removed in editing were excluded from analysis.

The Mean IBI was calculated for every hour in the recording and time synchronized with the local hourly mean magnetic field () measurements

2.4. Mathematical analysis

For the evaluation of HRV which reflects ANS activity, individual sensitivity to the local geomagnetic field a new nonlinear analysis methods - second order matrix analysis - were used.

Let two synchronous time series and are associated with the exploratory complex system. Let and () be non-random values with low-level noise added which has no particular impact on further calculations. Therefore algebraic methods can be used to analyze time series and . The algorithm may be divided into several steps [3]:

1 step. The values of and are normalized and modified time series and are obtained:

where and ( and ) are theoretical boundaries, e.g. physiological limits, and if these limits are unknown, then , , , . It is clear that in both cases , for all .

Step 2. Sequence of second order matrices are formed:

Step 3. Sequence of discriminants of matrices are calculated [4]:

Sequence of discriminants has important diagnostical properties to evaluate changes in described complex system. Let eigenvalues of matrix are and :

where , if and if ( denotes imaginary unit). Eqs. (5) and (6) yield and from this equality follow several properties:

1) The discriminant represents peculiarities of local variability of the processes.

2) If discriminant values are equal to zero it is clear that for all . The complexity of analysed system is low (zero complexity level).

3) If discriminant values are equal to constant (( then the difference (in quality and quantity) between time series and remain the same for all and the system remains invariant and static.

4) If is a periodic sequence , then two time series and describe two simple harmonic motion having the same frequency but different phase. In this case the system is in an ideal harmonic routine. The time of one period should be neither too short (complex system would be too primitive), nor too long (in this case system would be rather chaotic).

Let us notice, that if has quite high variability level, then the analysed dynamical system has high complexity level and from changes in the sequence of certain assumptions about system evoliution can be proposed.

Cardiovascular system sensitivity to the local geomagnetic field was evaluated using methods based on second order matrix theory. Data points of represent heart inter-beat-intervals () and represent local Earth magnetic field () parameters. RR intervals were normalized using physiological limits 300 milliseconds (ms) and 1500 ms. Limits for the local magnetic field were calculated , . Discriminant was calculated for each pair of the same time data points of parameters and . Besides discriminants, another sensitivity parameter was introduced. reflects cohesion between local Earth magnetic field and discriminants between and . Sensitivity was measured by the angle between regression line and discriminant axes:

where and are the coefficients of linear regression between (as axis) and (as axis).

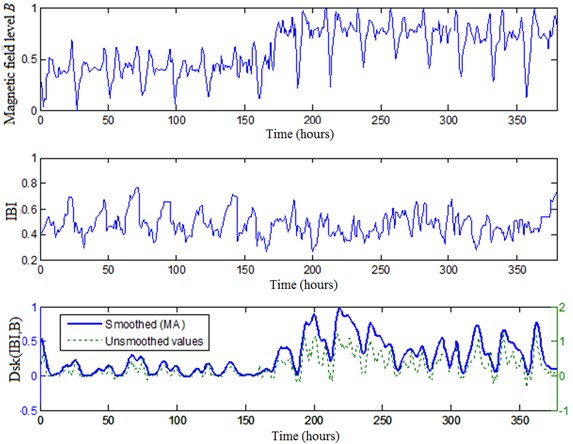

Fig. 1The synchronous data of one participant: local magnetic field level, IBI fluctuations at the same time, DskIBI,B

3. Results

For all the studied subjects s and magnetic field parameters, variations were averaged each hour’s period. In Fig. 1 data of one investigated female is presented – it clearly stands out day and night both in and activity – higher on the day and lower at night.

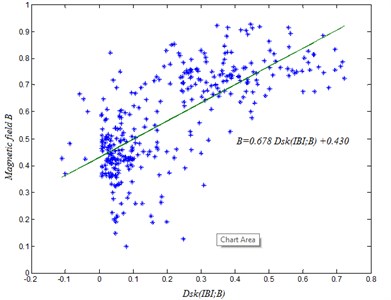

At about 180 hours of observation, the local magnetic field intensity increased and an obvious shift in the range of fluctuations of IBIs could be seen. This change is shown in Fig. 2 which presents the variation (Time – 180 h). Those variations where placed into phase plane. Personal sensitivity (Eq. (7)) to magnetic field changes (time scale 1hour) was calculated for every person. The example of sensitivity calculations of one investigated female is given in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2The dependence of Dsk(IBI;B) and local magnetic field B

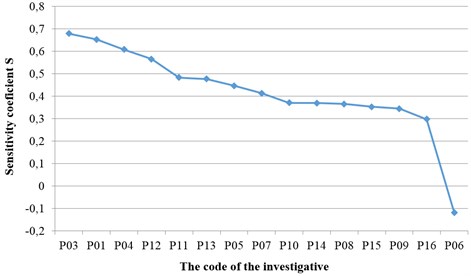

Different people have different sensitivity to local magnetic field. We have sorted the coefficients of sensitivity and in decreasing order – we could identify the people, who are the most sensitive to local magnetic field fluctuations and those, whose sensitivity is less. Also, we calculated the average sensitivity of the whole group. The results are presented in the Fig. 3.

Fig. 3Heart Rhythm sensitivity to Earth local magnetic field fluctuations in descending order of all investigated persons

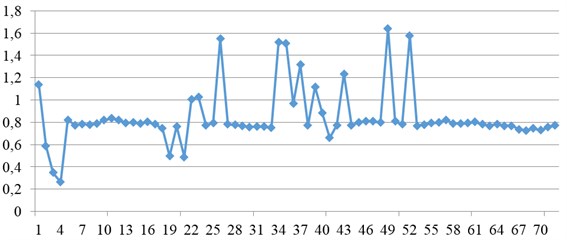

One participant had a negative sensitivity coefficient to the local magnetic field fluctuations (Fig. 3). Naturally, the question rises, – what was the reason for such character of sensitivity . We have explored in details the data of inter-beat-intervals. The short episode of inter-beat-intervals for this person is presented in Fig. 4.

It could be, that existing arrhythmia, big fluctuations in (Fig. 4) in person can cause the changes in human – Earth interconnection and rising up health problems for this person.

Participant age may be an important factor in human sensitivity to changes in the Earth’s magnetic field. Therefore, we calculated the correlations between sensitivity coefficient and age. The correlation was not significant (0.107) – so it appears that age (in studied persons age range 20-50) is not an important factor of sensitivity to local magnetic fields.

Fig. 4Irregular sequence of IBI of the participant with very small sensitivity to local magnetic field fluctuations

4. Discussion

Looking to original data and results of proposed matrix analysis for personal sensitivity to local Earth magnetic field fluctuations we can see, that every person has its own character of Human – Earth interconnection. In literature we can find a lot of interpretations, that ill person is more sensitive to the changes of magnetic field, or Moon phases or other climate condition changes. Our results can suggest that, just on contrary, person with some diseases, especially in heart, can lose its sensitivity to the changing surrounding; it means that adaptation abilities for such person are deceased. Abrupt changes in surrounding space without adequate adaptation can evoke big stress in person and just this stress can provoke unpredictable effects in organism itself – swinging in arterial blood pressure, stroke or myocardial infarction. Proposed methodology to evaluate personal sensitivity to local Earth magnetic field should allow studying dynamic of personal sensitivity and more exactly predict possible health disturbances.

5. Conclusions

The disturbances in the heart function can decrease the sensitivity to local Earth magnetic field and this can influence new problems in human-Earth interconnection and cause different health problems for the person. The proposed measure of human sensitivity to Earth magnetic field can help to evaluate personal possibilities to develop health problems.

Elaboration of the true mechanism of the delicate relationship between human heart rhythms and geomagnetic frequencies of the Earth is an important problem with many implications. The understanding of these relationships could full fill the existing gap of knowledge which could conceivably explain the persistent high morbidities and mortalities of cardiovascular disease in humans regardless of race, ethnicity and geographical location.

References

-

Stoupel E. G., Tamoshiunas A., Radishauskas R., Bernotiene G., Abramson E., et al. Neutrons and the plaque: AMI (n-8920) at days of zero GMA/high neutron activity (n-36) and the following days and week. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Cardiology, Vol. 2, Issue 1, 2011.

-

Stoupel E. G., Tamoshiunas A., Radishauskas R., Bernotiene G., Abramson E.,et al. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and intermediate coronary syndrome (ICS). Health, Vol. 2, Issue 2, 2010, p. 131-136.

-

Stoupel E. G., Wittenberg C., Zabludowski J., Boner G. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in patients with hypertension on days of high and low geomagnetic activity. Journal of Human Hypertension, Vol. 9, Issue 4, 1995, p. 293-294.

-

Baevsky R. M., Petrov V. M., Chernikova A. G. Regulation of autonomic nervous system in space and magnetic storms. Advances in Space Research, Vol. 22, Issue 2, 1998, p. 227-234.

-

Cornelissen G., McCraty R., Atkinson M., Halberg F. Gender Differences in Circadian and Extra-Circadian Aspects of Heart Rate Variability (HRV). 1st International Workshop of the TsimTsoum Institute, Krakow, Poland, 2010.

-

Malin SRCaS B. J. Correlation between heart attacks and magnetic activity. Nature, Vol. 277, 1979, p. 646-648.

-

Stoupel E. G. Sudden cardiac deaths and ventricular extrasystoles on days of four levels of geomagnetic activity. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology, Vol. 4, Issue 4, 1993, p. 357-366.

-

Villoresi G., Ptitsyna N. G., Tiasto M. I., Iucci N. Myocardial infarct and geomagnetic disturbances: analysis of data on morbidity and mortality. Biophysics, Vol. 43, Issue 4, 1998, p. 623-632, (in Russian).

-

Otsuka K., Cornélissen G., Weydahl A., Holmeslet B., Hansen T. L., Shinagawa M., et al. Geomagnetic disturbance associated with decrease in heart rate variability in a subarctic area. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 55, 2000, p. 51-56.

-

Cornelissen G., Halberg F., Breus T., Syutkinac E. V., Baevsky R., Weydahl A., Watanabe Y., Otsuka K., Siegelova J., Fiser B., Bakken E. E. Non-photic solar associations of heart rate variability and myocardial infarction. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, Vol. 64, 2002, p. 707-720.

-

Zenchenko T. A., Rekhtina A. G., Poskotinova L. V., Zaslavskaya R. M., Goncharov L. F. Comparative analysis of the response of microcirculation parameters and blood pressure to geomagnetic activity in healthy people. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine, Vol. 152, Issue 4, 2012, p. 402-405.

-

Gurfinkel Y., Breus T., Zenchenko T., Ozheredov V. Investigation of the effect of ambient temperature and geomagnetic activity on the vascular parameters of healthy volunteers. Open Journal of Biophysics, Vol. 2, Issue 2, 2012, p. 46-55.

-

Carrubba S., Frilot C., Chesson A. L. Jr., Marino A. A. Numerical analysis of recurrence plots to detect effect of environmental-strength magnetic fields on human brain electrical activity. Medical Engineering and Physics, Vol. 32, Issue 8, 2010, p. 898-907.

-

McCraty R., Deyhle A. The Global Coherence Initative: Investigating the Dynamic Relationship between People and Earth’s Energetic Systems in Bioelectromagnetic and Subtle Energy Medicine, Second Edition, 2015.

-

McCraty R., Childre D. Coherence: bridging personal, social and global health. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, Vol. 16, Issue 4, 2010, p. 10-24.

-

McCraty R., Deyhle A., Childre D. The global coherence initiative: creating a coherent planetary standing wave. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, Vol. 1, Issue 1, 2012, p. 64-77.